This memorial is now thought to be the most successful and beloved public work of our time. It is so simple, so elegant, that it makes its statement without even trying. The long arms of marble enclose us. We see the names of the dead. We are left with our thoughts.

The most arresting scenes in the documentary “Maya Lin: A Strong Clear Vision” are about the miracle that this memorial was even erected at all—about its opponents, who would have replaced it with something ordinary and mundane.

Today, when the memorial is universally beloved, such men as Pat Buchanan and Rep. Henry J. Hyde (R-Ill.) are not quick to remind you that they fought against it, in ways that do not reflect well on their judgment or taste.

The story of the memorial has entered the folklore. A national competition was held to choose a winning design. There were 1,441 entries, enough to fill a gymnasium. A committee sifted through them and finally decided on the stark design of Maya Lin, then unknown to them.

Although many of the entries came from famous professionals, the committee realized that Lin’s address was at student housing at Yale. She was an undergraduate, whose design was done as a class assignment. In a thicket of other entries featuring gaudy architecture and tired monumental themes, hers perfectly filled the assignment: It did exactly what it was intended to do, and absolutely nothing else. To visit it is to realize that it is perfect.

Her opponents did not see it that way. Drawn mostly from conservative ranks, they wanted a more traditional memorial, something you might find in a courthouse square, decked with the emblems of patriotism–eagles or flags or statues of soldiers. One called Lin’s design “insulting and depressing–a black scar in a hole.” Another asked, “How can you let a gook design this memorial?” Buchanan charged that one of the members of the selection committee was a communist. Hyde helpfully suggested that the design be changed to make it white instead of black, above ground rather than running with the contours of the land, and with a big flag at its apex.

Some of the most affecting scenes in the documentary show Maya Lin, then 20years old, tearfully defending her design at public hearings in Washington. The way she is attacked is illuminating: Her opponents did not much like the fact that she was young, a woman, and an Asian American, and their objections had less to do with design than with a desire to curry favor with veterans’ groups.

What saved the memorial was a combination of the design committee’s determination and the growing realization among veterans that this specialdesign had unique and irreplaceable qualities. Taste in art is a matter of letting the mind empty of all words about art, so that only shapes, tones and proportions remain. If what is left feels right, the art is good.

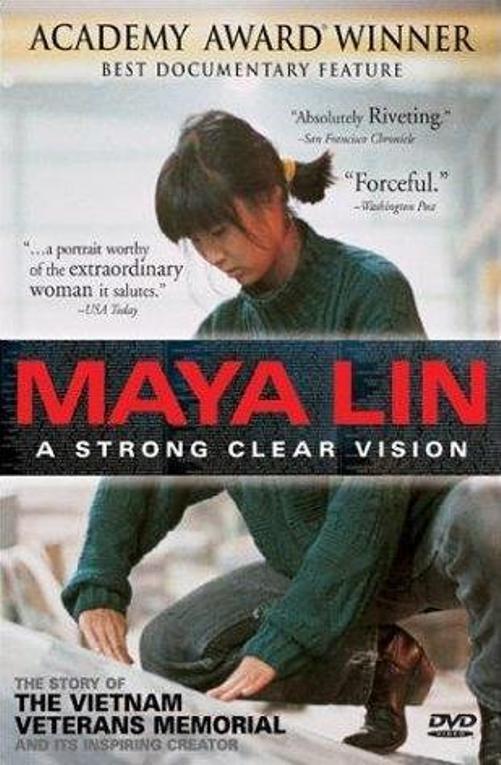

“Maya Lin: A Strong Clear Vision,” written and directed by Freida Lee Mock, tells the story of how Lin designed the memorial, and how it came to be built. It follows her over the next 14 years, as she matures from an insecure student to a confident professional, and designs other public works, including the Civil Rights Monument in Montgomery, Ala.

What is unfortunate is that Maya Lin herself does not emerge very clearly from the film. We learn a few facts about her, such as that her parents were the only non-whites in the Ohio town where she grew up, and that her father was dean of Fine Arts at Oberlin College. But we do not hear the testimony of those who know her well, or see anything of her private side. She is almost always onstage in some way when she appears in the film, and although she seems to be an interesting, complex person, the film does not tell us more.

“Maya Lin” won the Academy Award as the best documentary film of 1994, an award that will always be footnoted with the information that it won in the year when the academy committee rejected “Hoop Dreams.” It was not the best documentary of the year, but it is a valuable document. If you have been to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, you will want to see it. If you have not, it will make you want to go.