“Maurice” tells the story of a young English homosexual who falls in love with two completely different men, and in their differences is the whole message of the movie, a message I do not agree with. Yet because the film is so well made and acted, because it captures its period so meticulously, I enjoyed it even in disagreement.

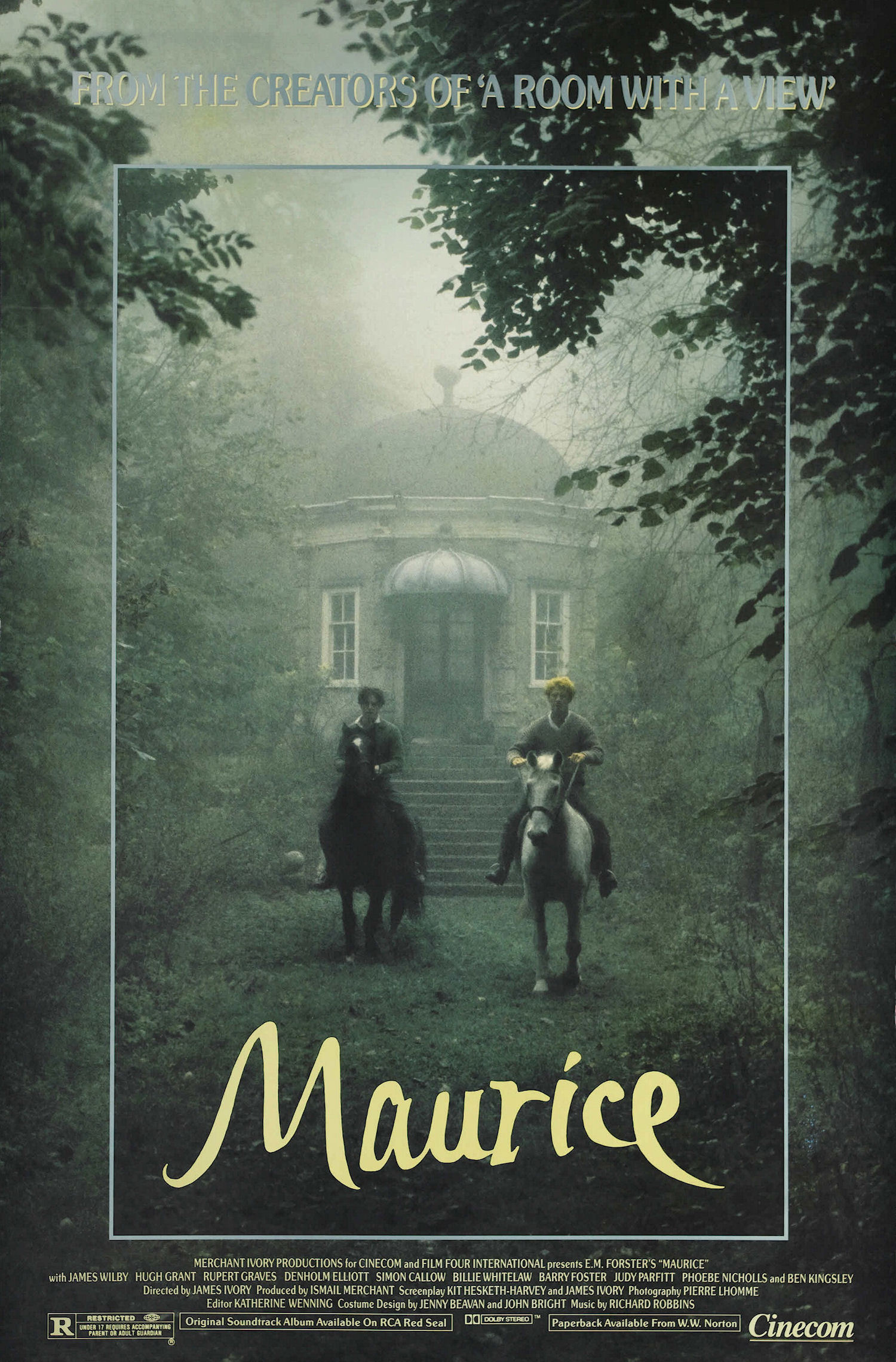

This is the first film from the team of James Ivory and Ismail Merchant since “A Room with a View,” and is based once again on a novel by E.M. Forster. Both books are about the gulf between idealistic romance and immediate physical passion, but otherwise they could not be more dissimilar. Maurice, which was written in 1914, was Forster’s attempt to deal in fiction with his own homosexuality, and the novel was suppressed until after his death.

The story takes place in the years before World War I, when homosexuality was outlawed in Britain and being exposed meant disgrace and ruin. At Cambridge, two undergraduates become close friends, and then one day in a moment of risk, one tells the other that he loves him.

The man declaring his love is Clive (Hugh Grant), an aristocrat who can look forward to a lifetime of wealth, privilege and perhaps public office. The man he loves is Maurice (James Wilby), also well-born, who may go into the stock market. At first Maurice is shocked and repelled by what his friend says, but later that night he climbs in the window to give him a quick, passionate kiss and whisper “I love you.”

From the first, their ideas about love are opposite. Clive is not much interested in the physical expression of love; he thinks it will “lower” them. His notions are more platonic and idealistic. Maurice, once he has been introduced to the idea of love between men, becomes a passionate romantic, and before long, Clive, the pursuer, becomes the pursued.

Clive fears exposure and disgrace. He sees homosexuality as something to be battled and overcome, and he breaks off with Maurice to marry, assume his family responsibilities and go into politics.

At first Maurice is shattered, and there are tragicomic scenes in which he seeks help from a hypnotist and the family doctor. Then he has a physical encounter of astonishing passion with Scudder (Rupert Graves), the roughhewn gamekeeper on Clive’s estate, and eventually both men determine to risk everything, throw their reputations to the wind and live together as lovers.

Merchant and Ivory tell this story in a film so handsome to look at and so intelligently acted that it is worth seeing just to regard the production. Scene after scene is perfectly created: a languorous afternoon floating on the river behind the Cambridge colleges; a desultory cricket game between masters and servants; the daily routine of college life; visits to country estates and town homes; the settings of the rooms.

The supporting cast (Ben Kingsley, Simon Callow, Billie Whitelaw, Denholm Elliott ) is unusually strong. Although some people might find Wilby unfocused in the title role, I thought he was making the right choices, portraying a man whose real thoughts were almost always elsewhere.

The problem in the movie is with the gulf between his romantic choices. His first great love, Clive, is a person with whom he has a great deal in common. They share minds as well as bodies. Scudder, the gamekeeper, is frankly portrayed as an unpolished working-class lad, handsome but simple. In the England of 1914, with its rigid class divisions, the two men would have had even less in common than the movie makes it seem, and the real reason their relationship is daring is not because of sexuality but because of class.

Apart from their sexuality, they have nothing of substance to talk about with each other in this movie. No matter how deep their love, I suspect that within a few weeks or months the British class system would have driven them apart.

In ignoring this reality, Forster and Ivory seem to be making the idealistic statement that love conquers all. Sometimes it does. Not usually. Physical sexuality is an important part of everyone, but especially after the first passion has cooled it is not the most important part. There comes a time when people need to simply talk to one another, to coexist as companions, and I doubt if that time could ever come between Maurice and Scudder.

By arguing that their decision to stay together was a good and courageous thing, “Maurice” seems to argue that the most important thing about them was their homosexuality. Perhaps in the dangerous atmosphere of homophobia in the England of 75 years ago, that might have seemed the case. But this film has been made in 1987 and shares the same limited insight.