There is a line of dialogue that comes late in “Marvin’s Room” and contains the key to the whole film. It is spoken by a woman who has put her life on hold for years, to care for a father who “has been dying for 20 years–slowly, so that I won’t miss anything.” Has her life been wasted? She doesn’t believe so. She says: “I’ve been so lucky to have been able to love someone so much.” The woman’s name is Bessie (Diane Keaton). She lives in Florida with her still-dying father, Marvin (Hume Cronyn), and a dotty aunt (Gwen Verdon), who wears some kind of medical device that is always opening the garage door. Bessie has discovered that she has cancer, but that her life might be saved by a bone marrow transplant. The only candidates for donors are Lee (Meryl Streep), a sister she has not seen in years, and Lee’s two children. If they are to be of any help, some old wounds will have to be reopened.

Lee lives in Ohio, where her precarious life has recently taken an upturn; she’s received her degree in cosmetology. It has also taken a downturn; her older son Hank (Leonardo DiCaprio) has just burned down the house. Her younger son Charlie (Hal Scardino) has reacted to this development as he reacts to most, by burying his nose in a book. Lee visits Hank in an institution, where he proudly reports, “They’re not strapping me down anymore!” “Don’t abuse that privilege,” she tells him.

The two sisters have not so much as exchanged Christmas cards in years, for reasons that they would certainly not agree on.

In broad outlines, this story goes on the same shelf with “What's Eating Gilbert Grape” another movie drama about a malfunctioning family (also starring DiCaprio). Both films have children who are the captives of chronically housebound parents; both have a child whose behavior is unpredictable and perhaps dangerous; both have a rich vein of bleak humor; both are about the healing power of sacrifice.

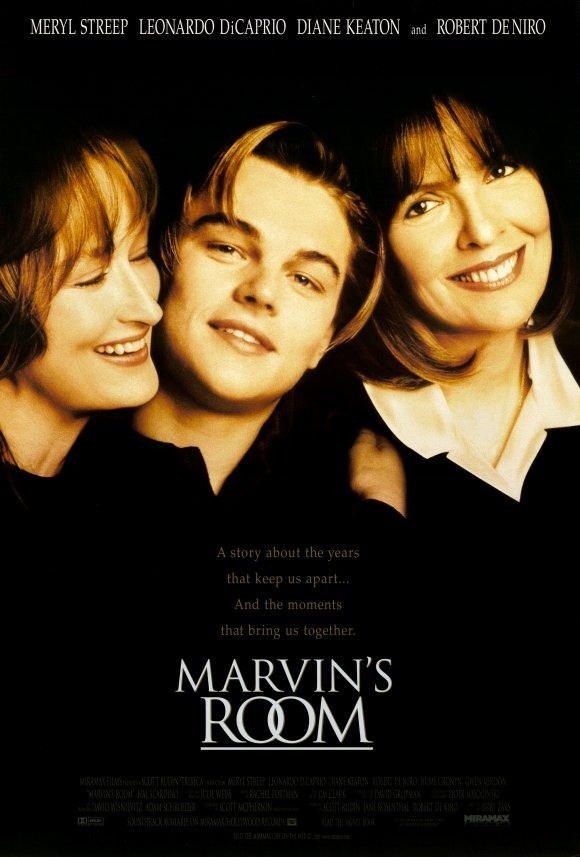

One of the big differences between the films, for a viewer, is that “Marvin’s Room” has so much star power: Not only Streep and Keaton, but also Robert De Niro, as a detached, apologetic doctor whose attempts to sound reassuring are always alarming. (How many spins can a doctor put on the words “test results?”) The famous faces make it difficult, at first, to sink into the story, but eventually we do; the characters become so convincing that even if we’re aware of Keaton and Streep, it’s as if these events are happening to them. (De Niro never becomes that real, and neither does Dan Hedaya, who is brilliant as his problematic brother, but that doesn’t matter because they function like the fools in a tragedy.) Lee piles Hank and Charlie into the car for the drive down South, during which she keeps Hank (on release from a juvenile home) on a very short chain. (Having burned down the house, he naturally is not allowed matches, so when he wants to smoke, she has Charlie, the 10-year-old, light his cigarette.) When she first sees Bessie, there is bluntness and disbelief: Both have aged 20 years, except in each other’s minds–and in their own.

Once the sisters are reunited, the material boils down into a series of probing conversations, and we sense the story’s origin as a play. (It was written by Scott McPherson, and first produced at Chicago’s Goodman Theatre in 1990; McPherson wrote a version of the screenplay before he died in 1992.) The stage origins, although we sense them, are not a problem because these two women *need* to talk to each other. There is a lot to say, and director Jerry Zaks lets them say it.

How do families fall apart? Why do many have one sibling who takes on the responsibilities of maintaining the “family home” and being the care giver, while others get away as far and fast as they can? Is one the martyr and are the others taking advantage? Or does everyone get the role they really desire? What “Marvin’s Room” argues is that Lee, by fleeing the sick people at home, may have shortchanged herself, and that Bessie, “chained” to the bed of her slowly dying father, might have benefitted. Or perhaps not; perhaps Lee was constitutionally incapable of caring for her father and was better off keeping out of the way. There is a point in “Marvin’s Room” where such questions inspired parallel questions in my own mind; all families have illness and death, and therefore all families generate such questions.

Is one of the three visitors from Ohio a match for the transplant operation? Will Bessie live? Will her father die? The true depth of “Marvin’s Room” is revealed in the fact that the story is not about these questions. They are incidental. The film focuses instead on the ways the two sisters deal with their relationship–which they both desperately need to do–and the way the sons learn something, however haphazardly, about the difference between true unhappiness and the complaints of childhood.

Streep and Keaton, in their different styles, find ways to make Lee and Bessie into much more than the expression of their problems. Hal Scardino has some wonderful moments as the “good” boy of a mother who is a borderline control freak (watch how he meticulously eats a potato chip just as she instructs). DiCaprio, on his good days, is one of the best young actors we have. Here he supplies the nudge the story needs to keep from reducing itself to a two-sided conversation; he is the distraction, the outside force, the reminder that life goes on and no problem, not even a long death, is forever.