One of the charms of Raymond Chandler’s detective novels is that you can’t figure out exactly what’s going on in them. Philip Marlowe is just pouring himself a drink from the office bottle when a chick knocks on the outer door, and within two chapters he’s involved with a bizarre cast of maybe two dozen characters, all of whom seem to know each other through relatives in Kansas or a friend in the pen.

Perhaps “The Long Goodbye” is the most complex Chandler plot of all. It ends with at least three sets of explanations, and a double reverse is thrown in after everything seems to be settled. You long for the simplicity of “The Lady in the Lake,” where the wrong drowned woman only seemed to be associated with the kingpin of the gambling boat.

Rather than bother checking up on his solutions, I’m generally inclined to trust Chandler. If he had been a lesser writer, his plots would matter more. But his books depend mostly on the texture and style of life in Los Angeles, and on the cynical intelligence of Philip Marlowe.

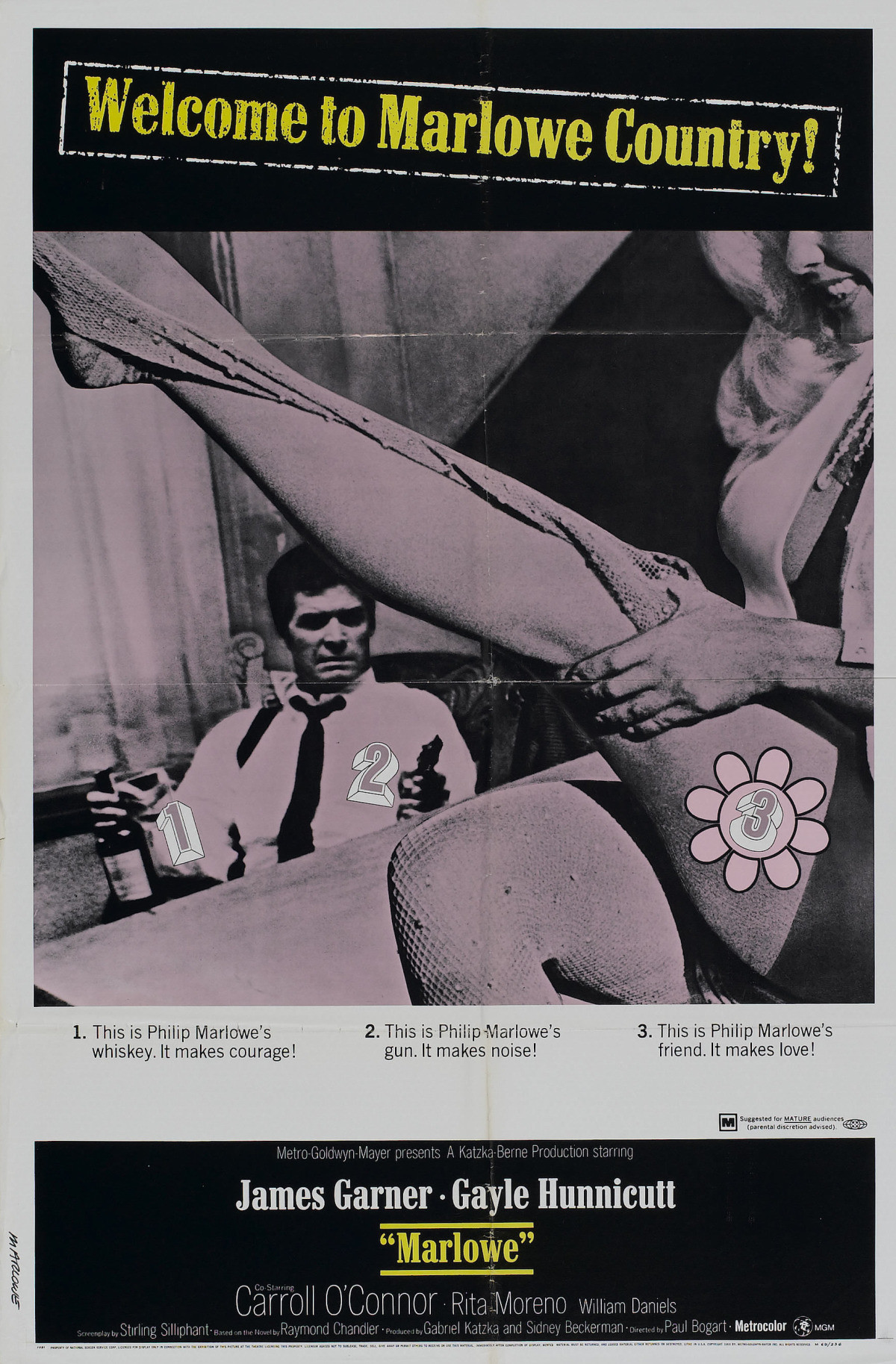

That’s probably why “Marlowe,” the latest movie to be based on a Chandler book, is not very satisfactory. Even though director Paul Bogart shot on location, he has not quite captured the gritty quality of Chandler’s LA. And James Garner, the latest Marlowe (after Robert Montgomery, Dick Powell and Humphrey Bogart), is a little too inclined to play for light, wry, James Bond-style laughs.

Bogey was the best Marlowe of all, and that was just as well because “The Big Sleep” (1946) needed somebody to distract from the plot. My contention is that the movie version of “The Big Sleep” never does explain what everyone was up to. But we don’t notice that because of Bogart and Lauren Bacall. In “Marlowe,” however, the loose ends are more distracting.

I’d be willing to bet that’s because the film was recklessly edited to make it shorter. Anyone familiar with the plot of Chandler’s “The Little Sister” (on which “Marlowe” is based) can spot the holes.

The film opens with Marlowe going to the rooming house in search of the missing brother. But we’re not given that all-important opening scene where the little sister visits Marlowe’s office, tells him her story, and hires him, so we can’t figure out what he’s after until it’s too late. From interior evidence in the movie, I’d guess the opening sequence was simply dropped.

That’s too bad, because detective movies have got to function at the level of plot, somehow, unless they star Bogart and are written by William Faulkner and just brazen their way through. “Marlowe” isn’t brazen enough. Somewhere about the time when the Japanese karate expert wrecks his office (in a very funny scene), we realize Marlowe has lost track of the plot, too.

So we watch suspiciously as Marlowe figures out Gayle Hunnicutt’s secret identity, and connects the child psychiatrist with the stripper and identifies the syndicate ice-pick specialist. The editing rhythm of the movie has completely broken down. We don’t care what happens next because we don’t understand what happened before. “Marlowe” becomes enjoyable only on a basic level; it’s fun to watch the action sequences. Especially when the karate expert goes over the edge.