You could say that after “We, the people,” the three most important words in American political history are: “Follow the money.” They were said by the anonymous insider who gave critical details about corruption in the Richard Nixon White House to Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein.

He was known only as “Deep Throat,” a nod to the popular porn movie starring Linda Lovelace that was released around the time that the two young Washington Post reporters, with his guidance, followed a trail that led them from a burglary at the Watergate office of the Democratic National Committee to the corruption that forced the first-ever resignation of a US president.

Except that Deep Throat, whose identity remained a secret for more than 30 years, never said, “Follow the money.” He never limited himself to confirming what Woodward and Bernstein had already uncovered. That was the Hollywood version, with Hal Holbrook speaking lines written by Oscar-winner William Goldman. Now, “Mark Felt: The Man Who Brought Down the White House” tells the story from the perspective of the man who was Deep Throat, based on his book and on extensive research and interviews by writer/director Peter Landesman (“Concussion”). In this version, Bob Woodward, who was 30 at the time of the break-in, is not the 40-ish movie idol Robert Redford. He is played as young, inexperienced, and nervous by 24-year-old Julian Morris.

The true story is murkier and more complex than Goldman’s version. Was it sacrifice and patriotism? Or, was it payback for losing out on the top job at the FBI when J. Edgar Hoover died? Who was Felt protecting, American voters or his agency?

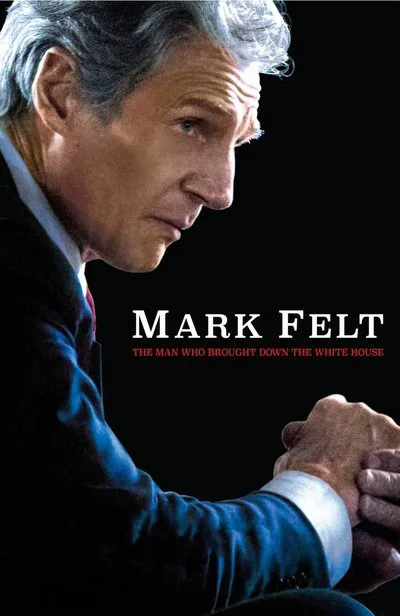

Landesman raises those questions in “Mark Felt: The Man Who Brought Down the White House,” with Liam Neeson, stoic as Felt, and Diane Lane, brittle and broken as his troubled wife. In this version of the story, shot with old lenses for a vintage look and with a haunting, noir-ish score from Daniel Pemberton, Felt is literally a shadowy figure, most often in the dark. We see him in the bleak, institutional setting of the old FBI building, with its nondescript desks and nondescript staff, and in his home, trying to help his wife and find his daughter.

The movie opens during Richard Nixon’s first term, as an angry crowd is protesting outside the White House and angry staff members near the Oval Office are asking, “Why aren’t we arresting anybody?” The sense of being under siege is palpable. Felt has been called in to speak with White House counsel John Dean (Michael C. Hall). It is a delicate, indirect, but pointed exchange to test Felt’s loyalties. “We know you to be a friend of this administration,” Dean says, “and we like to see our friends get what they deserve.” Felt responds with his own indirect but very clear statement. He coolly makes sure Dean understands that the FBI knows pretty much everything about everyone, but “all your secrets are safe with us.”

When Hoover dies suddenly, Felt is prepared. He is always prepared. “Put everything into motion,” he tells his staff, “No mistakes, not even one.” They immediately destroy all of Hoover’s private files. By the time Nixon aide L. Patrick Gray (an excellent Marton Csokas) shows up to ask for the files, Felt can blandly assure him that there are none.

Then Gray becomes acting Director, the first Director other than Hoover, and the first senior official who is not an insider. “It is what it is because no one from the outside has ever gone inside,” Felt says. In his view, the FBI has to be able to operate independently without any interference from anyone, including the Department of Justice and the White House.

When the order comes down to stop investigating the Watergate break-in, Felt goes to a friendly journalist (Bruce Greenwood), knowing he will ask Gray to confirm, and that will put pressure on him to keep the investigation open.

In Landesman’s view, Felt was a man who played by the rules very strictly, except sometimes the rules were his own. He was willing to put his closest associates under suspicion at enormous personal and professional cost by leaking information. He was careful not to use FBI resources to help find his missing daughter, except when he was not. He despised fellow agent Bill Sullivan for abusing FBI authority (played by Tom Sizemore, with just the right level of smug smarm), sternly warning him that “the dirty stuff is over,” but he also said, “People die because we stick to the letter of the law.” And he was later found guilty of breaking both the letter and the sprit of the law, and then pardoned. Felt is described as “the G-Man’s G-Man, competent, reliable, loyal.” This film encourages us to explore who and what he was most loyal to.

It is often said that “history does not repeat itself, but it rhymes.” This story can be seen as especially timely as another president is facing another investigation into events both during the campaign and while in office. Watching “Mark Felt,” we cannot help wondering not if but when this administration’s Deep Throat will appear.