How many artists—painters, photographers, sculptors—have been denounced on the floor of the U.S. Senate? If you can name one, it’s probably because Senator Jesse Helms of North Carolina, in a 1989 diatribe, argued that the photographs of Robert Mapplethorpe were so filthy that they deserved to be hidden from innocent eyes. Then, like a carnival barker outside a freakshow, Helms teased a black and white copy of one of the offending images.

“Look at the pictures!” Helms fulminated. Robert Mapplethorpe, who’d died of AIDS earlier that year, didn’t live to respond to Helms’ art-attack. By then, the artist was so revered, as a photographer of human faces, figures, and floral perfection that he’d already earned a mid-career retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art. A selection of his work called “The Perfect Moment” was touring U.S. art museums. But it was Helms’ denunciation, a pretext to cut funding to the National Endowment for the Arts, that made Mapplethorpe’s name synonymous with dirty pictures.

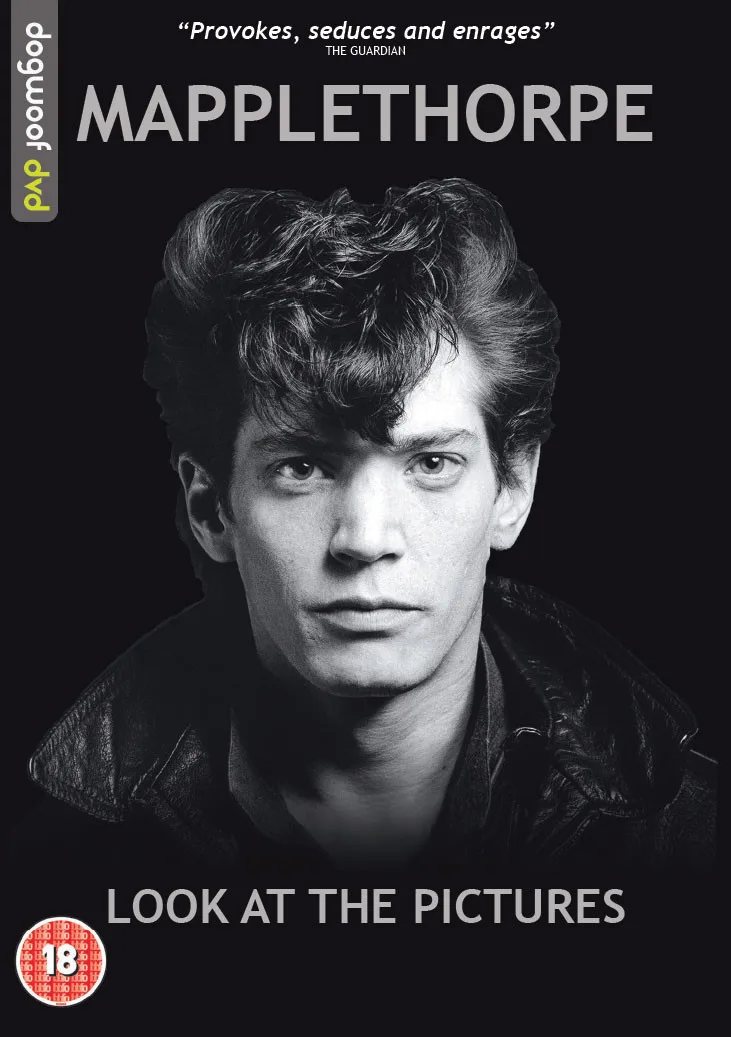

His work is strong stuff—and beautiful, too. For the most part, it’s anything but dirty. Shadowy is a better word. Now HBO’s “Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures,” directed by Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato, debuting Monday, April 4th, puts the artist’s life and career into perspective. The documentary premieres just in time for two major retrospectives of Mapplethorpe’s work at the Getty Museum and the LACMA. Fittingly, the film begins with the curators of both exhibitions sorting through the late artist’s massive collection (120,000 of thousands of images and negatives, plus diaries, films and more), deciding what will go on display. Gazing at the infamous “Mapplethorpe and Bullwhip” shot, a curator reverently remarks upon the photo’s composition, and suggests that the position of the artist’s free hand “almost looks as though he’s releasing the shutter.” Really? Everybody else is staring at 1). that whip going up his bum and 2). the horny, inviting look in Mapplethorpe’s eyes.

The directors do well when allowing Mapplethorpe’s friends, family, colleagues, and the artist himself—via archive interviews—to frame the conversation. Though Mapplethorpe speaks fondly of his childhood in Floral Park, Queens, brief interviews with the artist’s father are more revealing. While Mapplethorpe’s mother adored her middle son, his father discouraged his son’s interest in art and never accepted his sexuality. One early supporter, in addition to his older sister, was the family priest, who still has Mapplethorpe’s teenage artwork on the walls of his house.

Both comment on young Mapplethorpe’s extraordinary large, pale eyes. To his sister, young Bob was “a little devil.” To lovers, later on, he looked like Cupid, a satyr or a devil. For Patti Smith, who appears in archived interviews, photos, and in early film clips, Mapplethorpe was a first love and collaborator. (For a fuller picture of their relationship, read her autobiography Just Kids. Or wait for the upcoming film adaptation.)

Art school classmates and later colleagues remember Mapplethorpe’s charm, insecurity and ambition, which later had an ugly side: jealousy. Mapplethorpe’s much younger brother—later an artist in his own right—was crushed when his famous brother told him to change his name and stop “riding his coattails.” (They reconciled, and the younger Mapplethorpe movingly describes the agony of his brother’s final illness.)

More than a few interviewees chart Mapplethorpe’s interest in Roman Catholic imagery—Easter lilies, crucifixes, angelic faces, and bodies undergoing torture—putting it down to his churchgoing childhood. Mapplethorpe himself speaks of an unending search for “the perfect moment,” in light, in photography, in sexual experiences. The latter, sadly, became more risky as AIDS became a pandemic. As the artist explored his sexuality, including BDSM, with many lovers (some of whom were his models) he also pushed the boundaries of what the edgy New York art world would put on display. Mapplethorpe’s nudes—male, female, androgynous—were unlike anybody else’s. In several ravishing sequences, cinematographers Huy Truong and Mario Panagiotopoulos recreate Mapplethorpe’s artistic growth, as he progresses from photo collages to Polaroid to Hasselblad film camera. More amusing, though, is an irreverent recreation of “Ken Moody and Robert Sherman,” with the help of the models, the bald and beautiful men, black and white, who sat in profile for a much-reproduced shot. (It was projected on the NASDAQ building in 2014, for the Art Everywhere campaign) The two men crack jokes about the photo’s (over) interpretation. Was it a commentary on race relations? “Why was the black man behind the white one? “The white guy’s neck was longer, and he could do the pose,” says Moody. “Mine was too short.”

Mapplethorpe, ever in search of ideal proportions, found them in his favorite model, Milton Moore, who posed for “Man in a Polyester Suit,” dressed in the titular suit, except that his penis was outside of the suit. Though Moore’s face is not shown in torso-only shot, a Village Voice critic called the photograph “ugly, degrading, obscene” and “jerk off” material. (This is the photo that Jesse Helms waved in front of C-Span’s cameras and his fellow politicians.)

“The thing in the world that people are most afraid of is the penis,” says Jack Fritscher, publisher of Drummer magazine and the pithiest cultural commentary in this movie. “And Robert didn’t just show the penis, but black penis. A penis envy drives people insane either with lust or with fear.”

Mapplethorpe scared people, all right, and he still does. A few images tend to make men, more than women, wince; Museums and galleries and popular culture are full of naked women. If his work still shocks, it stirs the soul, for he was a classicist reaching for the perfect form. What remains, though, is Mapplethorpe’s last, haunting self portrait. He was weakened from disease, but still raging to create new work. He’s holding a skull topped cane and staring, with those eerie pale eyes, right at the camera, right at the viewer, or right beyond you, as though he sees something that you don’t, won’t, can’t see. That’s Mapplethorpe.