“Madame Sata” is a portrait of Joao Francisco dos Santos, a flamboyant, fiercely proud drag queen with a hair-trigger temper, who became a legend in the clubs and slums and prisons of Brazil. Born about 1900, dead in 1976, he spent nearly 30 of those years in prison, 10 of them for murder. “There’s something eating me up inside,” he tells a friend. Performing his drag act provides a release, but requires a lifestyle that attracts trouble.

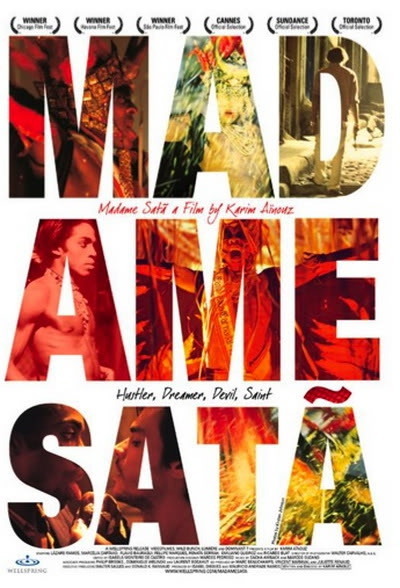

The character is never called Madame Sata during the film; we learn from the closing credits that he took the name, inspired by the de Mille film “Madame Satan,” later in life, when he began winning drag contests. The film opens not in victory but defeat: There is a long closeup of the hero, played by Lazaro Ramos, as his police record is read. It’s quite a reading.

The movie has the same familiarity with the slums of Rio as the great recent film “City of God,” but provides less insight into the characters. Joao Francisco remains a puzzle to the end of the film, a person who fascinates us but doesn’t share his secrets. The writer-director, Karim Ainouz, understands the milieu, and Ramos provides an electrifying, sometimes scary, performance, but it is always a performance, just as Joao is always, in a sense, onstage. Whatever is eating him up remains inside.

Homosexuality is an invitation to violence in the milieu of the film, but Joao is more than able to defend himself, and indeed makes a point of telling one of his attackers that being a queen makes him no less of a man. His domestic life is a parody of the nuclear family; he lives with a female prostitute named Laurita (Marcelia Cartaxo) and her child, not by him. They share a servant named Taboo (Flavio Bauraqui), who is more effeminate than his two employers put together. At home, Joao rules with the short temper and iron hand of the stereotypical dominant male, and is in many ways the most masculine character I’ve seen in any recent movie–certainly more macho than, say, Ben Affleck in “Gigli.” The story occupies the dives, cabarets, brothels and jail cells of the Rio underworld, where Joao starts as a backstage assistant to a European singer; in an effective early scene, he mimics the onstage performance from his position just offstage, and when a friendly bartender gives him a gig, at first he simply imitates the European woman’s act, while cranking up the voltage. He quickly becomes the object of curiosity and lust for the half-hidden but numerous gay population, and has a passionate, violent affair with a lover named Renatinho (Felipe Marques), who is a thief and sees no reason why being Joao’s lover and stealing Joao’s money should not be compatible.

If we never really understand Joao, there is another problem with the character, and that is: He isn’t very nice. I refer not to his crimes, but to the way he treats those who care for him. He clouts the faithful Taboo, insults his admirers, is not imperious so much as just simply hostile. That would not be an objection if the film dealt with it, but the film seems as uneasy about Joao as we are. He serves as our guide to the world of 1930s sex and crime in Rio, but there comes a point when we want to leave the tour and continue on our own, because this man’s demons are not only eating him, but devouring everyone around him.