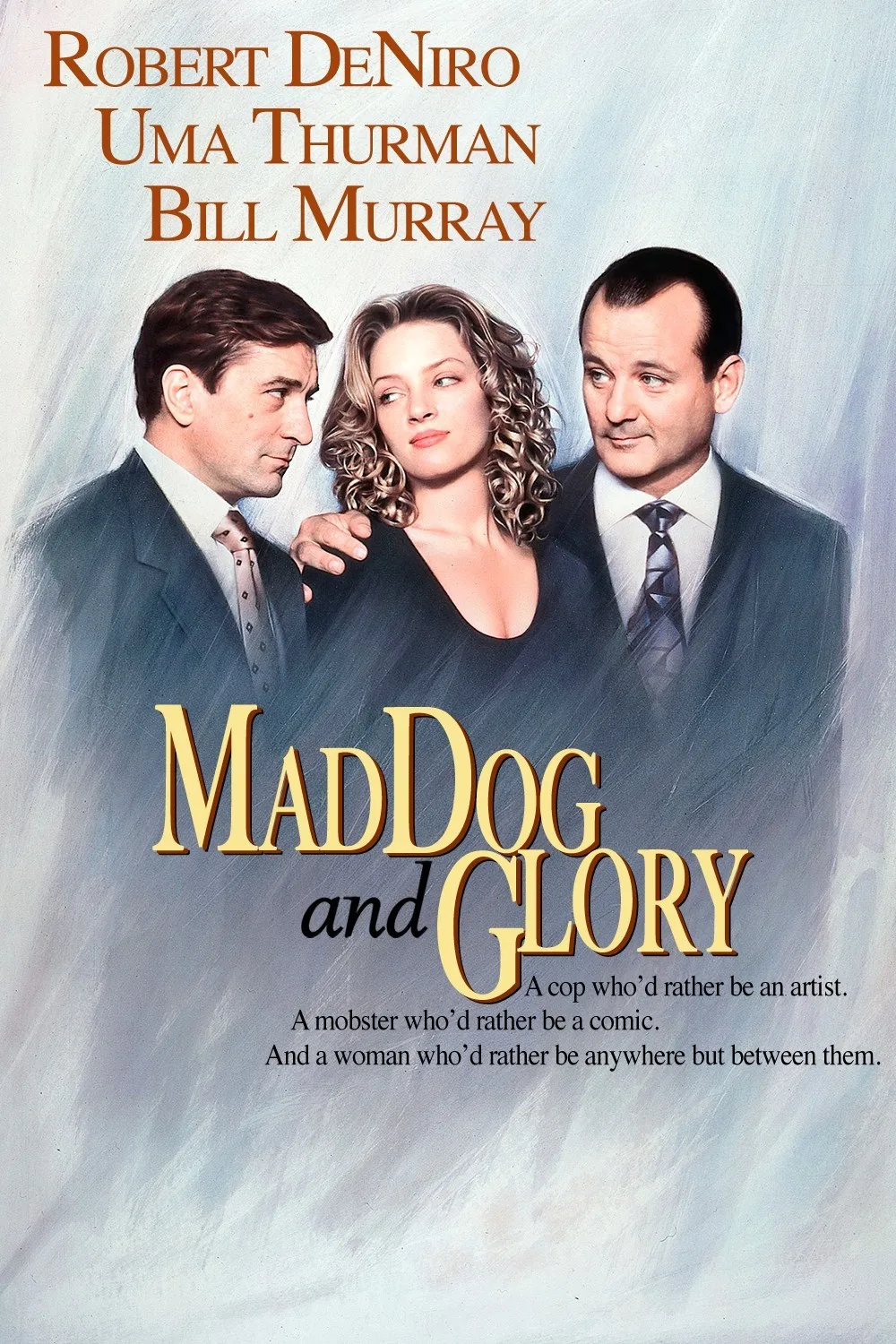

“Mad Dog and Glory” is one of the few recent movies where it helps to pay close attention. Some of the best moments come quietly and subtly, in a nuance of dialogue or a choice of timing. The movie is very funny, but it’s not broad humor, it’s humor born of personality quirks and the style of the performances.

The movie begins when Wayne, a timid Chicago cop (Robert De Niro), walks in on a convenience store holdup and accidentally saves the life of Frank, an expansive gangster (Bill Murray). Frank is not your average hood. He not only owns a comedy club, he performs in it.

He also collects bets, which is why he controls a young woman named Glory (Uma Thurman), who is trying to work off her brother’s gambling debt. One day she turns up at Wayne’s house and explains that Frank is giving her to him for a week, in gratitude.

This is a present Wayne does not want. Indeed, he is beginning to see that his entire relationship with Frank is a big mistake, since there is no way to be this gangster’s friend without being drawn into his activities. Wayne doesn’t even think of himself as a real cop. He’s shy and fears he is a coward. He works for the department as an evidence technician and frames his photos of dead bodies as if they were art; he’s a would-be Weejee.

The screenplay by Richard Price (“The Wanderers,” “The Color Of Money”) avoids the temptation to paint this situation in broad strokes. A dumb comedy might have been made of the situation, but this is a smart one. It’s about a man who begins the movie with no friends, and quickly gets one he doesn’t want and another, Glory, who terrifies him. She gives him kissing lessons, but he is uncertain about his bedroom skills, and when she tries to get his shirt off he explains that he should do some sit-ups. “Right now?” she asks. She can’t believe her ears. “No . . . I mean generally.”

The director, John McNaughton, is best known for the chilling “Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer.” This movie is completely different in theme, and yet it has the same quiet way of developing characters. The camera watches people while they gradually reveal themselves. Nothing is simply told to the audience.

For De Niro, Murray and Thurman, what happens is sort of magical. De Niro is known for his ability to get into characters by changing himself physically, and here, somehow, he seems to have shrunk. He seems shorter, more tentative. Murray, reining in his rapid-fire comic gift, comes across as the kind of guy who would love to be gentle and nice but was born with the wrong genes. Thurman, so elegant in other pictures, here becomes almost mousy in some scenes; Glory has low self-esteem, as indeed she should if she allows herself to be made into a thank-you note.

“Mad Dog and Glory” is the kind of movie I like to see more than once. The people who made it must have come to know the characters very well, because although they seem to fit into broad outlines, they are real individuals — quirky, bothered, worried, bemused.

By the end of the film, when the friendship between Wayne and Frank has come to blows, even the fight is handled differently. For some reason it reminded me of Jimmy Breslin’s observation that hoods never bury their victims deep enough because they don’t like to get mud on their shoes.