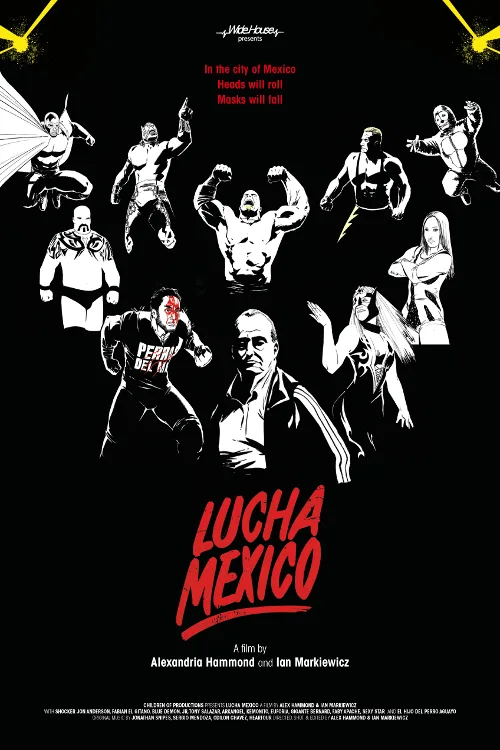

Why are sports such as boxing and wrestling thrilling to watch in narrative films but often tough to take in real life? Martin Scorsese’s “Raging Bull” and Darren Aronofsky’s “The Wrestler” aren’t compelling for their violence so much as for their ability to probe the psychology of their central male characters. What drives these men to repeatedly abuse themselves in fights designed to reduce their bodies to slabs of butchered meat? The aforementioned masterworks by Scorsese and Aronofsky offer quite a few potential answers to this question, none of which are explored with any real depth in Alex Hammond and Ian Markiewicz’s documentary, “Lucha Mexico.”

Certainly fans of the Lucha Libre brand encompassing Mexico’s beloved wrestling stars will find this repetitive assemblage of footage diverting, yet I quickly found it tiresome. There’s only so much one can glean from scenes of these guys posing for pictures while feeding the camera pat soundbites about how the love of fans serves as their primary motivation. From an outsider’s perspective, the cheering at these matches sounds less like an expression of love and more like the enabling howls heard amidst the bleeped expletives on “Maury.” At a time when the physical toll of punishing sports is being reevaluated in films such as last year’s “Concussion,” it’s difficult for me to get much enjoyment out of the theatrical machismo and unsettling masochism on display here, no matter how “staged” it may be.

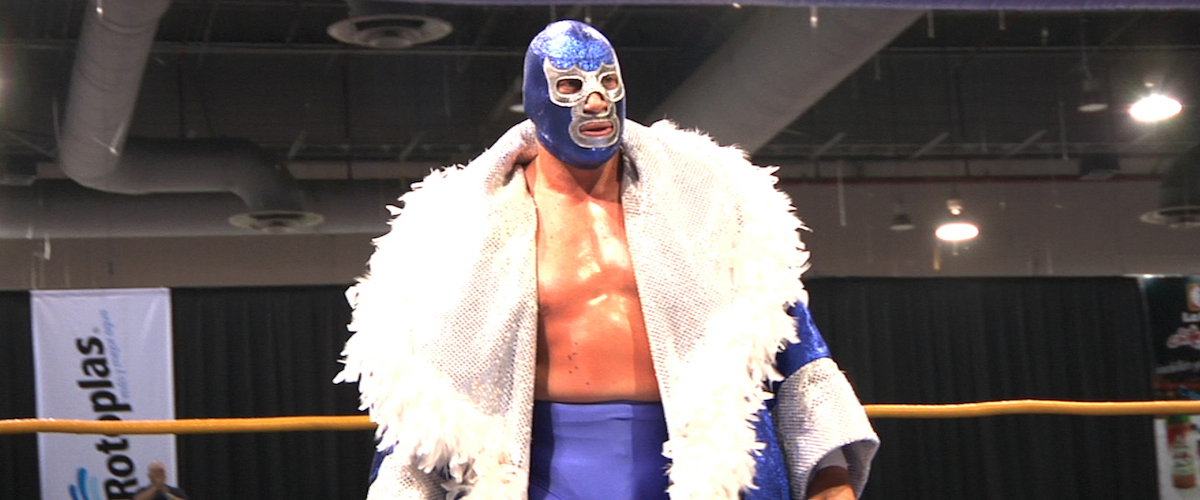

Perhaps limiting the film’s focus to a handful of wrestlers would’ve forced the directors to delve deeper into their subjects. Instead, the documentary skips so quickly from one masked face to the next that they all become interchangeable, with the obvious exception of KeMonito, the furry mascot famous for getting kicked around like a rag doll. The only recurring plot thread involves the recovery of Shocker (Jair Soria Reyna), whose ruptured patellar tendon sent him into a depression that is articulated but left off-screen. I wish the film spent more time with former wrestler Tony Salazar, who is briefly seen instructing students on how to perform wrestling moves in a way that will result in minimal injuries. An examination of the meticulous stunt work involved in a given match would’ve made for a far more interesting movie, but “Lucha Mexico” opts for holding its subjects at arm’s length, as if to preserve the “magic” of their superhuman abilities. That is how the public prefers to view them, with many young fans dressing up as their favorite wrestlers. In Mexico, these costumes appear to be as popular as those for Marvel superheroes. Indeed, when Jon Strongman tears off his shirt and flexes his towering muscles, it’s hard not to think of the Hulk.

Yet as much as these men would prefer not to admit it, they are mortals capable of being irreparably wounded or worse in the ring. After Strongman badly injures his arm, his opponent pummels the damaged limb repeatedly despite the man’s cries to stop. If safe words are required in “Fifty Shades of Grey,” shouldn’t they be mandatory in wrestling? Of course, that’s nothing compared to the Perros del Mal matches, where the blood of wrestlers is spilled via broken lights bulbs and barbed wire. Though the majority of audience members are said to be aged 18 and over, I spotted plenty of underage faces in the crowd and later on, at the gift shop. One interviewee suggests that “turbulent times in Mexico” have caused citizens to “identify with the bad guys,” and these words are accompanied by footage of protestors marching through the streets. Sadly, this is about as far as the filmmakers care to elaborate not only on this topic, but virtually every other one in the picture. Blue Demon Jr. says that the life of a wrestler is a solitary one, as we see him drive off into the darkness. Sexy Star reveals that wrestling helps her overcome depression. These are nice observations, but they mean nothing if the filmmakers don’t bother asking a follow-up.

What Hammond and Markiewicz are most gifted at is cinematography. I’d gladly watch this film’s entire B-roll again just to bask in the gorgeous Mexican landscapes and vivid snapshots of the cities, outdoor markets and parking lots where various matches occur. The reality of the surroundings make the phoniness of the wrestlers’ shtick all the more conspicuous. Occasionally the film will acknowledge the death of a young wrestler without lingering too long on the tragedy for fear of becoming downbeat. It’s aggravating to hear their surviving colleagues say that they are leaving their own fate “up to God,” since that conveniently enables them to not take responsibility for their actions. Resonating through all the sound and fury is Salazar’s pointed assertion that the rich would never subject themselves to this sort of profession, and that one needs the hunger to succeed—and to eat—in order to become a Lucha Libre legend. The implication is clear: disenfranchised people must channel their frustration one way or another, so why not apply it to a “sport” in which your systematic self-destruction is wildly celebrated by adoring fans? To me, there’s simply nothing here worth cheering about.