“Low Down” is a very good jazz movie and a very good heroin movie, if indeed there’s much practical difference between the two modes—and perhaps there isn’t. From “The Man with the Golden Arm” through “Bird” and “Mo Better Blues,” jazz has often been portrayed as a lifestyle that’s bound up in addiction to heroin, gambling, sex, cocaine, alcohol, or some mix. When you watch films about the music and the people who perform it, you may start to wonder if jazz itself is an addictive pursuit: music as metaphor. There hasn’t been much of a commercial percentage in playing jazz for many decades, at least not compared to hip-hop, rock, country or bubblegum pop (which are their own kinds of crap shoots, of course). Even in the 1950s—when jazz became more exploratory art than danceable entertainment, yet still spawned commercial hits like Miles Davis’s “Kind of Blue” and become a signifier of sophistication (see Hefner, Hugh)—it filled what seemed, compared to other pop forms, like a niche market. So why play jazz ? For art’s sake. For pleasure. For the rush.

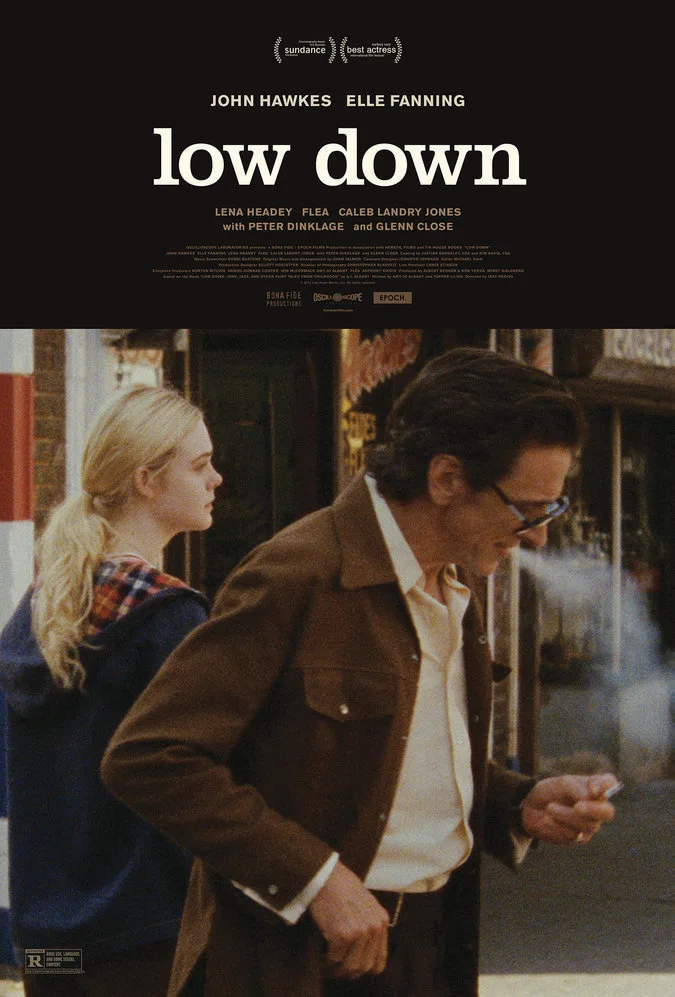

It sure seems as though Joe Albany (John Hawkes), the real-life pianist and heroin addict at the center of “Low Down,” plays jazz and shoots dope for all those reasons; well, those reasons, and the fact that he’s a junkie hanging with other junkies, which isn’t a situation that lends itself to sobriety. Directed by cinematographer Jeff Preiss, a jazz fan who shot the 1990 Chet Baker documentary “Let's Get Lost,” the film is based on a memoir by Joe’s daughter Amy (Elle Fanning), and unfolds mostly through her eyes, circa 1975 or so. They share a small apartment in downtown Los Angeles, in a building full of prostitutes and junkies. “I can’t keep myself straight here,” Joe confesses in a moment of clarity.

But Amy adores her dad and respects his artistry, and because she’s lived her whole life in his chaotic world, she doesn’t see her situation as dire. It’s just her situation, and as long as dad’s around, it’s fine. The film’s carefully maintained point-of-view explains why this objectively bleak tale feels mostly warm and gentle. I like to think that’s why Priess shot “Low Down” in soft, grainy 16mm, favoring brown and russet and gold and creamy-white: we’re seeing this world as Amy sees it, through hopeful, loving eyes.

There’s plenty to love about Joe, but Amy’s hope is misplaced, and in time she’ll figure it out. I’ve described “Low Down” as a jazz movie and an addiction movie, but both are folded into a coming-of-age film. It’s about a young woman who’s becoming a grownup and realizing that her father is an adult, too, but one whose lifestyle (as an artist as well as a junkie) gave him license to never grow up, at least not in the way that “square” parents must.

Joe lives from gig to gig, and blows a lot of the money he makes on dope. Like many addicts with kids, he genuinely loves his daughter, but expresses that love in the form of conversations and fleeting, spontaneous adventures rather than through the mundane day-to-day grunt work of parenting. (He’s the kind of guy who can make it seem as though he’s listening to you, even though his mind is elsewhere.) Amy and Joe don’t go out much as father and daughter, and we rarely see them talking about Amy’s schoolwork, her personal development, or the future. He brings her to gigs, and invites other musicians over to the apartment to jam while she listens, but that’s not the same thing as fathering a child. Preiss lets the harsh reality of Joe’s neglect enter the film subtly, as when Amy’s grandmother, Gram (Glenn Close), has Amy over for dinner and exclaims, “Look at you, girl, you eat like a linebacker—I love it!” In another scene, a hungover Joe wakes Amy up and tells her to hurry to school, and she groans, “It’s the weekend.” A smile creeps across Joe’s face. “It is, isn’t it?” he says. “That’s great news.”

Amy’s adoration of Joe is rooted in real love of his art. There’s a wonderful moment where we see Amy finish listening to a tune on vinyl, then lift the needle up and place it at the start of the cut to hear it again. The rapt expression on Fanning’s face during live musical performances is just right (Hawkes, a guitarist, fakes Albany’s acrobatic finger-work brilliantly, and Preiss rewards his diligence by showing us his hands in close-up). We get the impression that Amy was oblivious to Joe’s cycles of addiction throughout most of her young life. Her dad seems functional most of the time, and charming, at times dashing—Hawkes moves his slender frame with a dancer’s grace, and holds his cigarette with jaunty elegance—then he’ll go on a binge, and reveal self-pitying, abrasive, neglectful sides. He’ll disappoint her and make her cry. Then he’ll smile at her in a certain way, or crack just the right joke, and she’ll forgive him. You’d call Amy an enabler if she were mature enough to have any say in her life, but she’s not. She’s tall and beautiful and on the verge of adulthood, but she’s a kid. She’s starting to see through Joe now, though, and it’s painful.

Much of her dawning awareness creeps in via encounters with secondary characters. Gram thinks her boy Joe hung the moon, comes to his aid when he’s at his lowest, and sometimes behaves more like a starstruck groupie than a mother. “They’re all touched by something wonderful,” she says of jazz heroes, her eyes flashing. “They’re touched by God.” Alain (“Game of Thrones” costar Peter Dinklage), a sweet and charismatic artist neighbor, squats in an abandoned apartment in the building, and does a better job of hiding his addiction than Joe does, but not well enough to hide it from Amy. Joe’s best friend Hobbs (Flea, a ringer for middle-aged Chet Baker) seems like a rock, but he’s a junkie, too, and he romanticizes the connection between drugs and jazz by suggesting that God takes junkie musicians young “because they’re so good.” Amy’s alcoholic mother, Sheila (Lena Headey, another “Game of Thrones” regular), at times seems jealous of her daughter, and verbally cuts her down as one might a romantic rival.

“Low Down” drives home the idea that whatever you experienced as a kid is “normal” to you, even if you grew up seeing things kids shouldn’t see, and enduring things they shouldn’t have to endure. One of the film’s most quietly disturbing scenes, Amy sees a man knock on a neighbor woman’s door, then keeps watching as the woman opens it, lets the man in, and tells her young son to wait out in the hall. A subsequent shot of Amy and the boy watching TV in the building’s lobby captures the instant affinity that children of addicts feel. Fanning’s performance in this mostly reactive role could scarcely be improved; we understand every tremor of feeling in Amy from watching her move and listen and have her heart broken. Preiss’ film does a consistently excellent job of explaining the lure of jazz, and the psychology of addicts, their enablers and their children, without explaining anything. We just watch and understand.