In the center of the frame, very close to the camera, hangs a studio microphone that could be mistaken for a vintage Soviet communications satellite. Chet Baker, 58, is recording Jimmy Van Heusen and Johnny Burke’s “Imagination.” His voice isn’t quite as soft and papery as it used to be, but the image — like every shot of Baker in Bruce Weber’s “Let’s Get Lost” — is about the face, not so much the music.

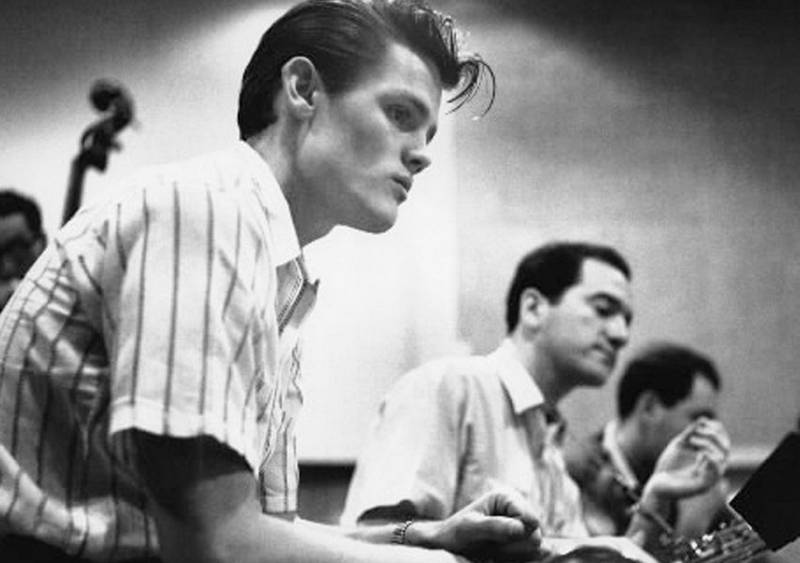

That face — gnarled and craggy beneath the mustache, the rimless eyeglasses and the headphones — fills most of the screen on the right. On the left, in the background and partially obscured by the mike but still in focus, is the face of pop musician Chris Isaak. No reason is given for Isaak’s presence in the studio, but he’s there for his face, too — to provide a dramatic visual contrast, and to remind us of the beautifully sculpted one Baker used to have on those Pacific Jazz and Riverside album covers of the 1950s.

“Let’s Get Lost” is an atmospheric black-and-white portrait of a jazz trumpet player, an exemplar of West Coast “cool jazz” in the age when rapid-fire bebop was hot, whose life, career and face were ruined by his various addictions. That’s not an unfamiliar story among musicians of any stripe. But you can see what attracted Weber, the famous fashion photographer best-known for his iconic, homoerotic Calvin Klein and Abercrombie & Fitch advertising images, to this particular subject.

In his 20s, Baker could have been the prototype for Weber’s underwear models. He had the sleek and breezy James Dean look, the soft-focus enigmatic reticence, the sensitive masculinity that was just on the edge of androgyny. And, shortly before this film was originally released in 1988, he jumped, fell or was pushed to his death from a hotel window in Amsterdam. Dutch authorities ruled it an accident.

The great jazz photographer William Claxton, an arbiter of cool himself, talks about the first session he did with Baker, and how fascinated he was by the young man’s charisma.

Later, when he got into the darkroom, he found he’d neglected the other musicians he was supposed to shoot and wound up with rolls of film of the trumpet player. We see Claxton and his grease pencil going over contact sheets of these photos in the movie.

Baker auditioned for Charlie Parker, who chose him for a 1952 series of West Coast gigs. Shortly thereafter Baker joined Gerry Mulligan for the revolutionary “piano-less quartet.” Their long and legendary engagement at the Haig nightclub in Los Angeles made Baker a star, but the quartet broke up in 1953 when both Mulligan and Baker were arrested at the end of a set. Police also raided the house where both men lived with their wives, and found heroin and marijuana.

In 1954, Pacific Jazz released the album “Chet Baker Sings,” a popular success that showcased Baker’s smooth, vibratoless voice. He sang like a horn — a muted trumpet or an oboe played at almost a whisper. It won him a larger audience but cost him some credibility with jazz fans who may already have considered him and his music a little too pretty for their tastes.

“Let’s Get Lost” (which might also have been called “You and the Night and the Music”) documents Baker’s final year, intercut with archival footage and interviews in which Baker and others look back at a rough and peripatetic life that was soon to end. But what you remember most are the shots of Baker roaming around Santa Monica, Calif., in what feels like endless late-afternoon sun, or riding at night in the back of a convertible with a woman on each arm. The passing streetlights and shadows play across the rugged terrain of his face, a topographical map of where he’s been, and how lost he got along the way.