Their mother has died and their father thinks he might be able to find work in the war industries of the South, and so Jay and Arty go to live with their grandmother in Yonkers in the opening moments of Neil Simon’s “Lost in Yonkers.” This is a fairly standard opening for Simon, who often sees life through the wide-open eyes of teenage boys. But the film of Simon’s Broadway play has a special quality to it. All of the performances are good, but one of them, by Mercedes Ruehl, casts a glow over the entire film.

Ruehl plays Aunt Bella, the daffy, movie-loving younger daughter of the formidable Grandma (Irene Worth). There is a possibility, subscribed to by everybody but never quite put into words, that she is mentally ill. She’s certainly flighty. She overflows with enthusiasms, and then is brought low by tormenting doubts, and her optimism has hard sailing into the gales of Grandma’s scorn.

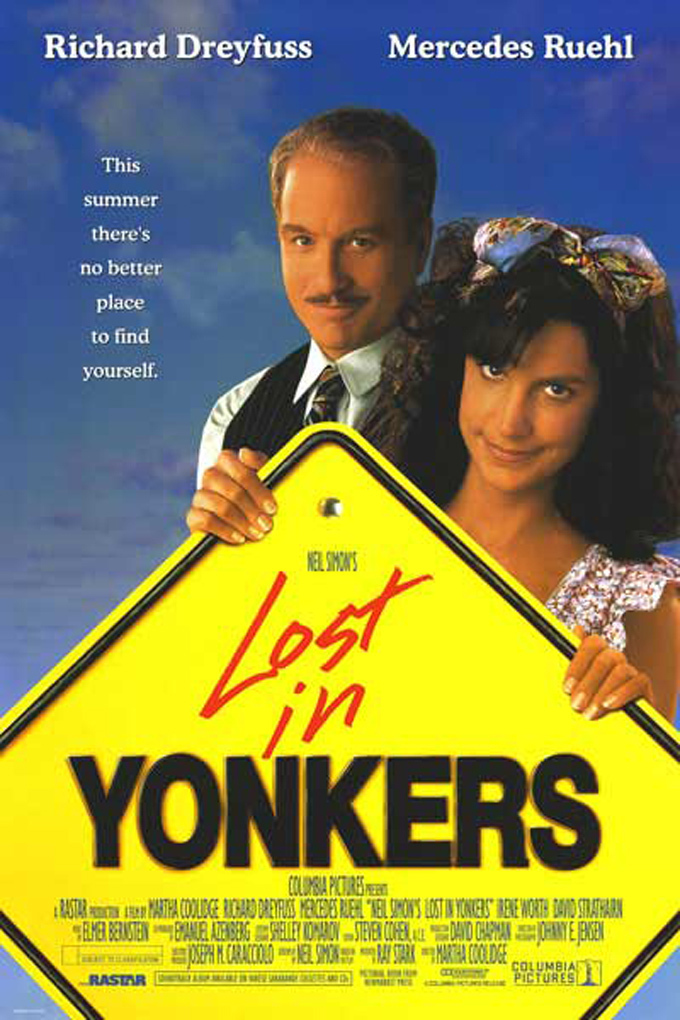

For the boys, Aunt Bella is a pal in a strange new land. Jay (Brad Stoll) and Arty (Mike Damus), 15 and 13, are fascinated by the half-heard family legends they now see being demonstrated. They’ve heard a lot, for example, about Uncle Louie (Richard Dreyfuss), the black sheep of the family, who is said to be a “henchman,” although the exact nature of his duties is much in doubt. And they have gathered, from the tone of their father’s voice, that Grandma, his mother-in-law, is not among his favorite persons. No wonder. She is cold, strict, forbidding, and unforgiving. It must be God’s special justice that she has been given two such trials as Bella and Louie as her children.

The boys move into Grandma’s apartment upstairs from her candy store, and begin to settle into the unpredictable life of the eccentric family. Aunt Bella lives in a fantasy world of movies, which she describes to them in loving detail. And they meet her boyfriend Johnny (David Strathairn), who is an usher at the movie palace, and seems to be mentally unbalanced in an opposite direction from Bella: She is expansive, he is introspective, so they make a nice fit. Meanwhile, Uncle Louie seems embroiled in the Yonkers version of a mob war, and gives them stern warnings against playing with firearms – especially his.

Both Mercedes Ruehl and Irene Worth played the same roles on Broadway, and here they are well served by the director, Martha Coolidge, who avoids the trap of letting their characters become larger than life. “Lost in Yonkers” is material Coolidge seems comfortable with, perhaps because she also directed “Rambling Rose,” another film in which a strange and rare woman was at the center of an unconventional family.

All of the material is seen through the eyes of the boys, especially Jay, the older, who will do a lot of growing up during this summer – as will Aunt Bella, who sometimes seems like his contemporary. The film is a series of small discoveries and victories, over life, over handicaps, and especially over Grandma’s autocracy.

The key role is Ruehl’s. The first time we see her, she is bravely cheerful, as if she believes the happy endings in the movies she loves so much. Only gradually do we begin to understand the darker side of her character, the unhealthy way in which her mother has suppressed her natural exuberance. By the end of the movie, when Aunt Bella finally finds a way to live life on her own terms, we’re almost surprised how much we’ve come to care about her.