The opening frames of “Lost Angels” explain the title. We see the words “Los Angeles,” and then graffiti is used to add a “t” and cross out an “e.” What we are seeing is the message of the movie: In the affluent Los Angeles upper middle class, children are the lost angels – cast aside by parents who are dazzled by new jobs, more money and second marriages.

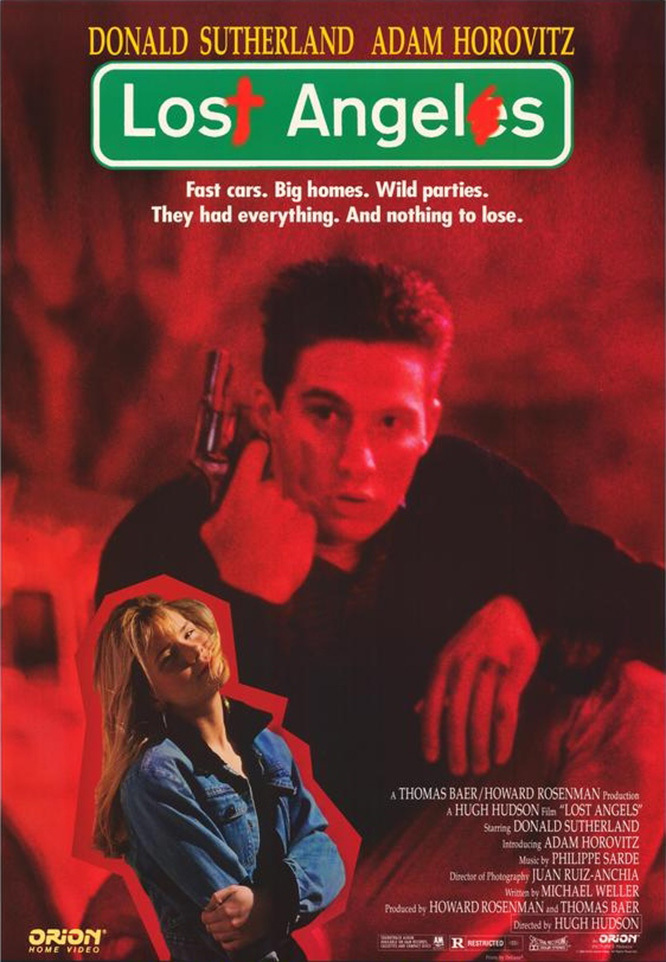

The hero of the film is a taciturn, cynical 17-year-old named Tim Doolan (Adam Horovitz). As we meet him, he is being locked up in a privately run juvenile detention center by his mother and stepfather, who have lied to him about where he is going. In flashbacks, we see that this kid has gotten into a lot of trouble. He was with a girlfriend when she drove the family car into the swimming pool, and earlier he was in a gang fight and picked up a gun from the street that was used in the battle.

There is a sense in which this boy is indeed a delinquent and another sense in which he is the victim of circumstances and very bad luck. (I kept thinking of the ending of “Angels With Dirty Faces,” in which Pat O’Brien says he became a priest and Jimmy Cagney became a mobster only because O’Brien could run faster from the cops.) Whether or not he’s a “bad” kid, he’s an angry and alienated one who at first needs to be strapped to a bed in a padded cell.

Enter the movie’s hero, a psychiatrist named Loftis (Donald Sutherland). He is intelligent and empathetic and begins to care about this kid. And then the movie explains the structure of the juvenile center, in which the youths grade themselves on levels one through four on the basis of their progress. If “Lost Angels” has a surprise, it is that it makes this private detention center its real target. Most of the staff members are seen as time-servers with no real interest in the kids, and Sutherland scornfully dismisses the management, which is concerned only with a profitable bottom line: “When insurance paid for a year in a place like this, we said it took a year to help a kid. Now insurance pays for three months, and, presto, it takes three months to turn a kid around.” The movie’s plot is a series of advances and setbacks for Tim, who is torn between the progress he makes on the inside and the evil influence of his half brother (Don Bloomfield) on the outside. The brother, a psychotic, tries to force Tim into shooting a gun into a crowd of teenagers, and the tension in this scene is genuine and frightening. Maybe some of Tim’s misplaced loyalty to his brother comes from a need to belong. The movie argues that all of its “lost angels” have been squeezed out of families, and Tim has a love affair with a deeply unhappy young woman whose mother clearly wishes to be rid of her.

“Lost Angels” avoids a lot of obvious cliches, treats its characters with dignity and develops them as specific individuals. This is particularly true of the Sutherland character; we get a glimpse of his home life suggesting that he is more dedicated to the kids at the center than to his own family. The portrait of Tim is also interesting: Horovitz doesn’t affect the glamorous moodiness of the usually Hollywood teenage performance, but plays a truly withdrawn, bitter teenager whose real thoughts come out mostly in interior monologues.

All of these qualities make “Lost Angels,” which was directed by Hugh Hudson, into an intelligent, well-crafted picture. And yet while I was watching it, I remained strangely unmoved. There was a certain coldness and anger that had nothing to do with the characters, that was directed almost at life itself, that seemed to say the dedicated people were only fooling themselves.

This anger coexists uneasily with the unconvincing last scenes of the movie, in which we are expected to believe Tim makes a decision that nothing in the earlier scenes has prepared him for. Ending a downbeat movie with a happy ending is nothing new, but “Lost Angels” is so unremitting in its fundamental critique of an entire society that the optimistic ending seems almost like a cruel joke.