Since “Lords of Chaos” is a dramatization of real-life events, there are some spoilers in the following review. We’ve tried to clearly indicate where those spoilers are, but if you don’t want to know what happens in the film, proceed with moderate caution.

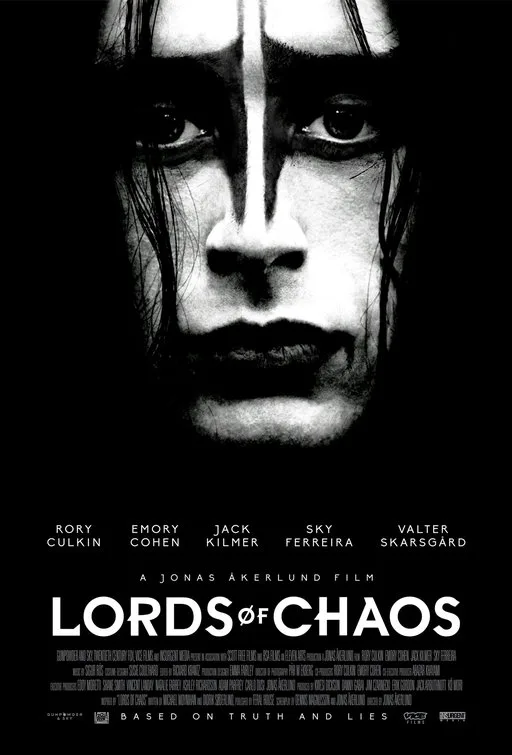

“Lords of Chaos”—a new horror film that dramatizes real, heavy-metal-related murders committed in Oslo during the early 1990s—is half-warm, half-frigid. Ultimately, the icy half of the film—pretty much any scene involving violence or juvenile humor—ruins the warm half. Which is unfortunate, since “Lords of Chaos” is infrequently a thoughtful black comedy about the world of heavy metal music, and the way that its fans often seek, but rarely sustain authenticity through their favorite bands and personas. Still: the cold half (ie: the important half) of “Lords of Chaos” is so ugly and mean-spirited that I couldn’t really enjoy the other parts of the film that work, not even Rory Culkin’s fantastic lead performance, or the on-screen chemistry that he shares with supporting actress Sky Ferreira (as photographer/love interest Ann-Marit).

“Lords of Chaos” seemingly begins by encouraging viewers to decide for themselves what happened when the Oslo-based black metal enthusiast Euronymous (Culkin) tried and failed to start a scene based on the vague concept of “true Norwegian black metal.” Euronymous puts a lot of neurotic care into his public persona as the ghost-paint-wearing lead singer of Mayhem, a somewhat formative (in real-life) black metal group. In a rare concert scene, we see the kind of high energy that Euronymous and his guys chase after throughout much of the film’s 117-minute run time. It’s a solid concert scene, one that captures the manic highs and crushing lows of attending a great heavy metal concert.

But that sequence isn’t characteristic of the rest of “Lords of Chaos.” Much of the plot concerns Euronymous’s frenemy relationship with heavy metal poseur turned heavy-duty black metal band leader Christian (Emory Cohen), who later changes his name to Varg, and then “The Count.” Varg, in real life, was the leader of Burzum, a semi-influential black metal group. [SOMETHING OF A SPOILER] Varg’s also a convicted murderer, so you can probably guess how this particular story ends.

Writer/director Jonas Akerlund (along with co-writer Dennis Magnusson) deserve some scrutiny for making a fictional drama that is, at heart, about the death and meaning of real-life people and their respective legacies. But, instead of arguing whether or not “Lords of Chaos” is a responsible work of fiction, I’d rather talk about how Akerlund and his collaborators tell this particular story. For starters: they use lots of pop culture signifiers–music cues, poster art, and movie footage–to quickly establish a connection between their audience and their characters. When Euronymous and Varg aren’t butting heads, they’re surrounding themselves with metal LPs—Metallica’s “Kill ‘Em All,” Motörhead’s “Bomber,” and, uh, Black Sabbath’s “Seventh Star”?—and gory horror movies, like “Dead Alive,” “The Evil Dead,” and “A Nightmare on Elm Street.”

This is a weird mix of titles, mostly because these characters would probably head-bang along with music by metal bands like Venom, Death SS, and Slayer. Still, you can tell that some care went into the assembly of the film’s collection of pop culture references (there are some strategically-placed Venom fliers in a few scenes). And the fact that most people can recognize these pop culture artifacts (if only by their iconic cover or poster art) suggests that these songs, albums, and movies were chosen in order to make a redundant comment about how Euronymous and Varg are both “poseurs,” since authenticity is all they seem to talk about (in the film, anyway).

Still, the fact that the bands and films that Akerlund and Magnusson name-check are semi-well-known—and not just among the film’s target audience of horror/metal fans—does say something about the target audience of “Lords of Chaos.” This is a movie that seems to have been made for people who have fond memories of their metal-loving youth, but have grown far apart from (and maybe even a little contemptuous of) their past. That reading is confirmed any time that Culkin, as Euronymous, uses voiceover narration to speak to his character’s constantly unsettled emotions. Sometimes his narration seems to be intentionally obnoxious, like when Euronymous mysteriously analyzes himself: “Everything that happened made me immune to reality. I had no more limitations.” There are, however, also a couple of funny character-driven lines of voiceover narration, like when Euronymous, speaking of Varg, says “My future and success disappeared behind his actions. F**k.”

Then again, Akerlund’s grisly depiction of violence is disgusting because it is, presumably, supposed to be both sensational and character-revealing. Akerlund’s shock tactics—brain matter, blood spatter, and realistic-sounding howls of pain—are neither shocking nor thoughtful. Instead, these needlessly over-long scenes confirm—rather than reject—the kind of immature cynicism that Akerlund superficially rejects. “Lords of Chaos” may sometimes feel like it was made by an empathetic, big-hearted anthropologist. But those moments aren’t as important or memorable as the scenes where Akerlund and his colleagues mock the same characters that they sometimes appear to like.