Casey (Josh Lavery), the wandering figure in Craig Boreham’s gay character study “Lonesome,” first emerges only passingly like Jon Voight in “Midnight Cowboy.” Yes, both are travelers bound from their respective quaint country landscapes toward the big city. But unlike Voight’s Joe Buck, Casey’s journey from the Australian outback to Sydney, while equally as reliant on sex work, isn’t in service of riches. For him, intercourse is a purely mechanical and necessary act, not a horny endeavor. Casey most desires a bleak ending—he wants to see the ocean so he might die by suicide in it.

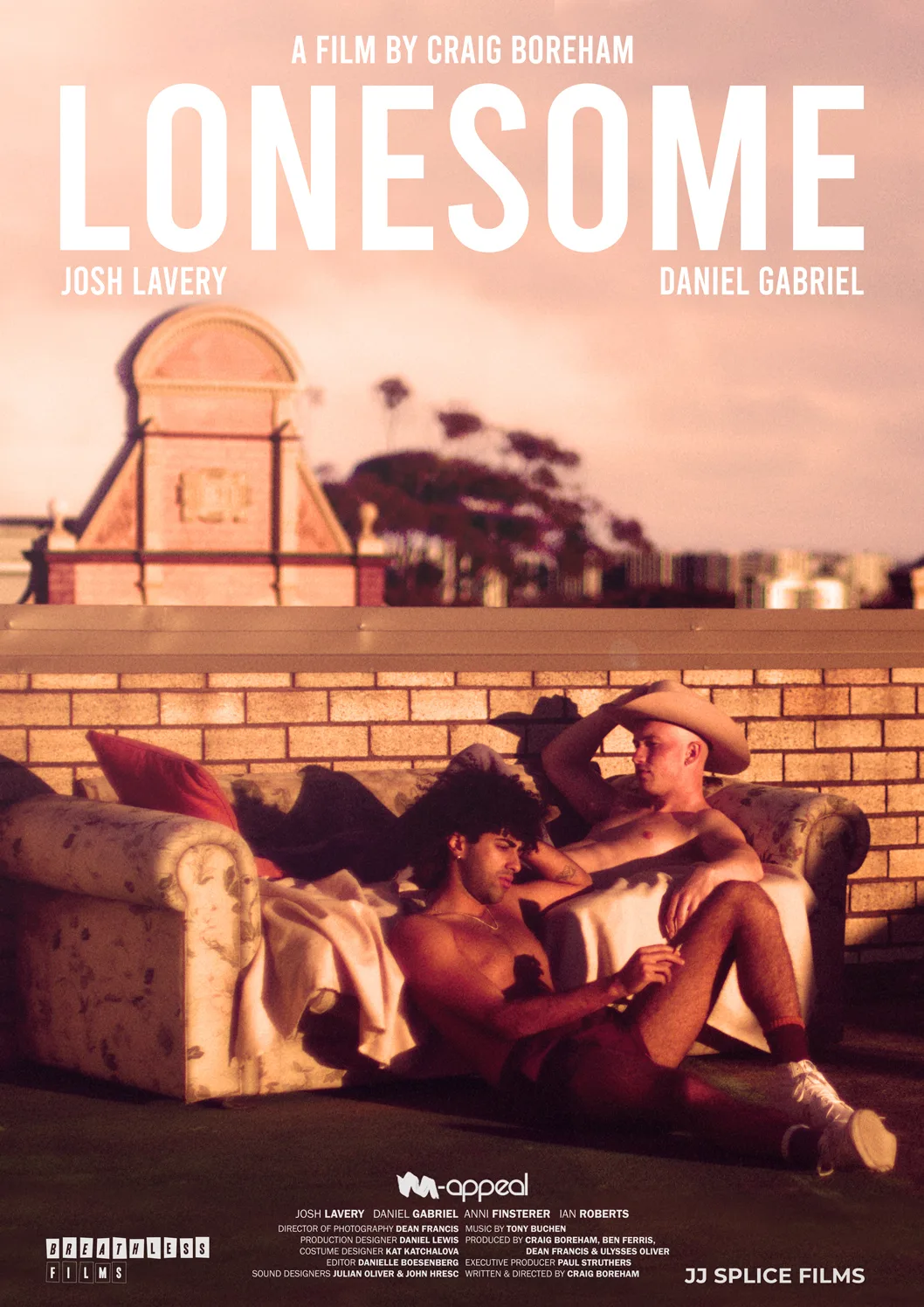

Cinematographer Dean Francis’ warm photography, stained with sunny hues of marigold, belies the aching feeling inside of Casey as he traverses a highway flanked by fields of grain toward a truck stop. The white cowboy hat topping his boyish face and muscular frame attracts a bearded trucker; their bathroom encounter is the first of Casey’s many dispassionate jobs. But that changes in Sydney when he engages in a threesome with Tib (a cheeky Daniel Gabriel). For the first time in what must feel like a long time, Casey opens himself up physically and emotionally to the possibility of being hurt.

Nightly talks and daily walks occur, in which Casey shares with Tibs the sad backstory—heartbreak, a crashed truck, and running away from home—that would make for a soul-stirring country song. He also begins to feel comfortable in Tibs’ presence, partially processing the self-guilt and self-hate that initially caused him to shut down. Casey could be happy; he could reconnect with his estranged parents; he could even make a home with Tibs. But the inability for him to fully forgive himself pushes and elongates Boreham’s romantic drama.

Casey doesn’t initially seem to be the most intriguing subject for a character study. He moves so passively through this world; I’d be surprised if his dialogue amounted to more than a couple of pages. He has a stoic mien, one guided by a sharp desire not to be discarded once more. Much relies on how Lavery’s body interacts with these new urban spaces. He’s often half-closed in, not totally collapsed away from experiencing, yet not broad enough to be at ease.

Lavery and Boreham make sex as much a character arc as a site of passion, a rare trick in modern film. By the midpoint of “Lonesome,” sex isn’t just a means of survival for Casey; it’s a silent language expressing his desire to be loved. Lavery’s once-frozen frame melts away; varnished in the queer purple and violet lighting of Tib’s simple apartment, he turns limber. Away from those inviting confines, when the anguish he always feared arrives, his austerity returns and sex reformulates from a purely robotic, transactional pursuit to one of self-punishment. Lavery is fully committed to these flights of adoration and angst, even when the film veers to being too on the nose (particularly the parallel Boreham sketches of parents who have misunderstood their gay sons).

The ending is equally all-too neat, a bit of wish fulfillment that borrows more from a bevy of teen romances than the bleak character-driven narrative originally promises. Still, as Casey ran full-speed through Sydney, lifted away from his terrible weight, fully open for love, I was swept up by “Lonesome,” and glad that it sees a reality outside of harm and unrelenting trauma for its gay protagonist. Despite its name and copious sex, “Lonesome” is surprisingly wholesome.

Now playing in theaters and available on digital platforms on March 7th.