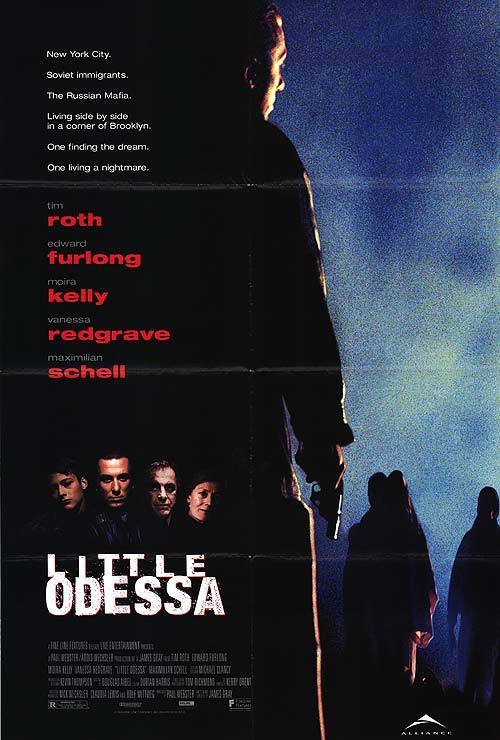

In the opening moments of “Little Odessa,” a hit man played by Tim Roth walks quickly across a street toward a man on a park bench, and shoots him dead. Then he goes to a telephone to report that the job has been done. He learns that his next job will take him to the Brighton Beach neighborhood of Brooklyn. Not there, he says. He can’t go back there.

But he does, and we learn that he has been running from this neighborhood – settled by Jews from Russia – and from his past, ever since he was banished by his father for committing an earlier murder, maybe his first. Still living there are his father, his mother, a kid brother, and the girl he walked out on when he fled Brighton Beach.

It is, we gather, risking his life to go back there, but the hit man, named Joshua Shapira, is not too clever about escaping notice. He checks into a local hotel for several days. He visits a social club, and sits in the window. Soon even his kid brother, Reuben (Edward Furlong), knows he’s back, and they meet at Nathan’s on the boardwalk, on a cold winter day. He looks up the girl, Alla (Moira Kelly), and they go to a movie. And he returns home to visit his dying mother (Vanessa Redgrave), but his father (Maximilian Schell) throws him out, crying “murderer!” Soon Joshua is involved again in the local crime scene; he has been hired to do a killing, others are hoping to kill him, and there are old scores to settle. One of them is with his father, who takes off his belt to beat the younger brother, and who is eventually humiliated by Joshua – made to disrobe in a vacant field and anticipate his own death. This scene, inspired perhaps by an equally unpleasant but more plausible scene in “Miller's Crossing,” brings the film to a shuddering halt.

The whole undercurrent of child abuse in the movie is unconvincing, and doesn’t provide much of an explanation for Joshua becoming a hit man. I felt as if the whole crime plot of the movie had been imposed on the underlying story, to make the project more commercial.

Tim Roth is an amazingly versatile actor; compare this character from Brooklyn with his Cockney thief in “Pulp Fiction” and his foppish con man in “Rob Roy.” He does what he can with his character, but the story, written and directed by James Gray, is neither a family drama nor a crime melodrama, but a series of disconnected scenes that play like exercises – some of them very good ones.

Consider, for example, the kid brother. Edward Furlong is a skillful actor, but what can he do with a role that requires him to materialize uncannily at key moments, just so he can witness things it is unlikely he would even know about? Or what about the father, played by Schell, who is written as such a ham-handed heavy that he bursts through credibility? And what, given the movie’s Jewish milieu, are we to make of a closing scene in which a furnace is used as a crematorium? There is symbolism there, I’m sure, but I don’t feel like working it out, and I don’t think the movie has earned it.

Gray, the filmmaker, is 25 years old, and this is his first film. It plays a little as if he put everything into it that he ever wanted to say, or do, in a movie – even a closing shoot-out sequence that uses such stagy choreography it feels more like film school than any possible sequences of real events. As I watched a subtle play of shadows on sheets hanging on a clothesline, it seemed to me that the movie had raised too many serious issues to turn into a visual exercise at the end. It’s a set piece when a dramatic scene is needed.

Some individual passages are very well done. A quiet, sad discussion, for example, between the father and his mistress. A conversation between Joshua and the girl he left behind.

A final talk between Joshua and his mother. None of these need a contrived crime plot to make them work, and when “Little Odessa” is over, you wonder if it wasn’t really meant to be a family drama – and that the idea of making the son a hit man was an afterthought, to make the project more attractive to investors.