All hell breaks loose. The daughter runs from the table, and the brother follows her out of the house, trying to make peace. We can see the two women are bitter enemies, although the mother probably would not see it that way; she uses prayer as a weapon, just as much as her daughter uses alienation and aggression.

This scene sets up the emotional conflict in “Light of Day,” which shows a family tearing itself apart despite the best efforts of the son, who wants to hold things together at almost any cost. This is a family drama, all right – but not one of those neat docudramas in which every character comes attached to a fashionable problem, and all the problems are solved in the same happy ending. The family in “Light of Day” is more like your average, everyday, unhappy family in which the biggest problem is that some of the members quite simply hate each other.

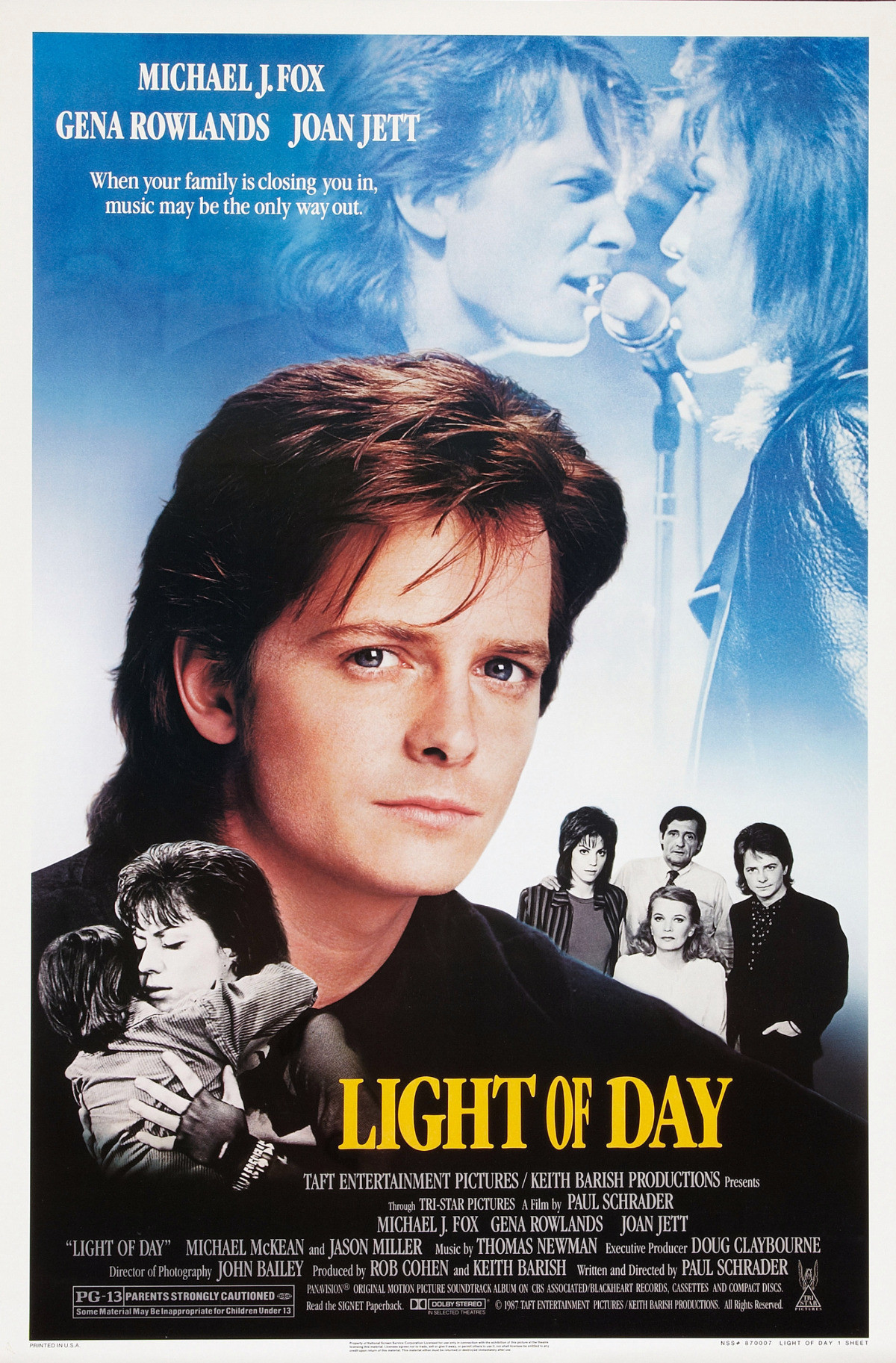

Writer-director Paul Schrader tells his story against a working-class background in Cleveland. The parents (Gena Rowlands and Jason Miller) have worked hard for their share of suburban respectability. The children (Michael J. Fox and Joan Jett) play every night in a rock band, and although Fox has a daytime job in a factory, Jett’s life is on hold until the sun goes down; she says rock ‘n’ roll is the most important thing in the world, and she means it.

Because she means it, life is not very healthy for her little boy, a son born out of wedlock by a father she refuses to name. It is this child that has driven the wedge between mother and daughter. And soon he becomes the focus of her relationship with her brother. When their band goes on a tour – sometimes playing for no more than a few bucks and free drinks – the child is left in cheap motel rooms, and Fox doesn’t approve of that. Jett, filled with anger and defiance, won’t listen to his objections, and Fox stands by helplessly, trying to be all things to all people.

His family clearly is a matriarchy, a battleground between two strong women. The father, played by Miller as a sensitive wimp, long since has given up, and now Fox is trying to play the peacemaker, the responsible one, almost the parent. He obviously idolizes his sister (and, in a way, his mother), and so there are painful moments, very well acted, in which he hurts because he cannot help these people he loves.

The movie is subtle in its construction. Schrader doesn’t telegraph his ending in the first half-hour, and indeed the movie’s one fault is that it sometimes seems without a clear direction.

At first the film seems to be a blue-collar story. Then a family drama. Then a rock ‘n’ roll movie. But then we see the rock band is going nowhere, and the center of the story turns back to the family, after the mother becomes seriously ill. And it’s the illness that provides the payoff, in strong and painful bedside scenes between Rowlands, Fox and Jett.

This mother may be sick, but she knows exactly what she’s doing, and Rowlands’ acting is powerfully, heartbreakingly effective. The mother uses love, truth, insight and a measure of cynical calculation in an attempt to control what will happen to her family if she dies.

She always has been a controller, and the possibility of death only inspires her to new efforts.

“Light of Day” is told like a short story by Henry James or Raymond Carver, in which the last few moments and the final words throw everything else into focus. And there is so much pain and anger in the film’s ending we can speculate that this is the real material that Schrader only touched on in “Hard Core,” his 1977 film about a runaway daughter’s rebellion against her strict, fundamentalist family.

“Light of Day” is arriving in theaters with an advance reputation as a rock ‘n’ roll film, and yet Joan Jett, the movie’s one certified rocker, gives the most surprisingly good performance. In the bedside scene with Rowlands, she is acting in the big leagues; Rowlands is inspired and Jett rises to the same inspiration, and there’s a rare, powerful chemistry. Fox, playing a weak, conciliatory character, is the right balance for these two strong woman, and Miller, kept in the background in most of his scenes, has one searching speech in which he tries to explain what has happened to his family.

Schrader has been one of the most consistently interesting writers and directors of the last decade. Try to find the thread connecting his screenplays, such as “Taxi Driver” and “Raging Bull,” and his films as a director, such as “Blue Collar,” “Hard Core,” “American Gigolo,” “Cat People” (1982) and “Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters,” and what you come up with are wildly different characters with one thing in common: Their pasts keep them imprisoned, and shut them off from happiness in the present. Here is his most direct and painful statement of that theme.