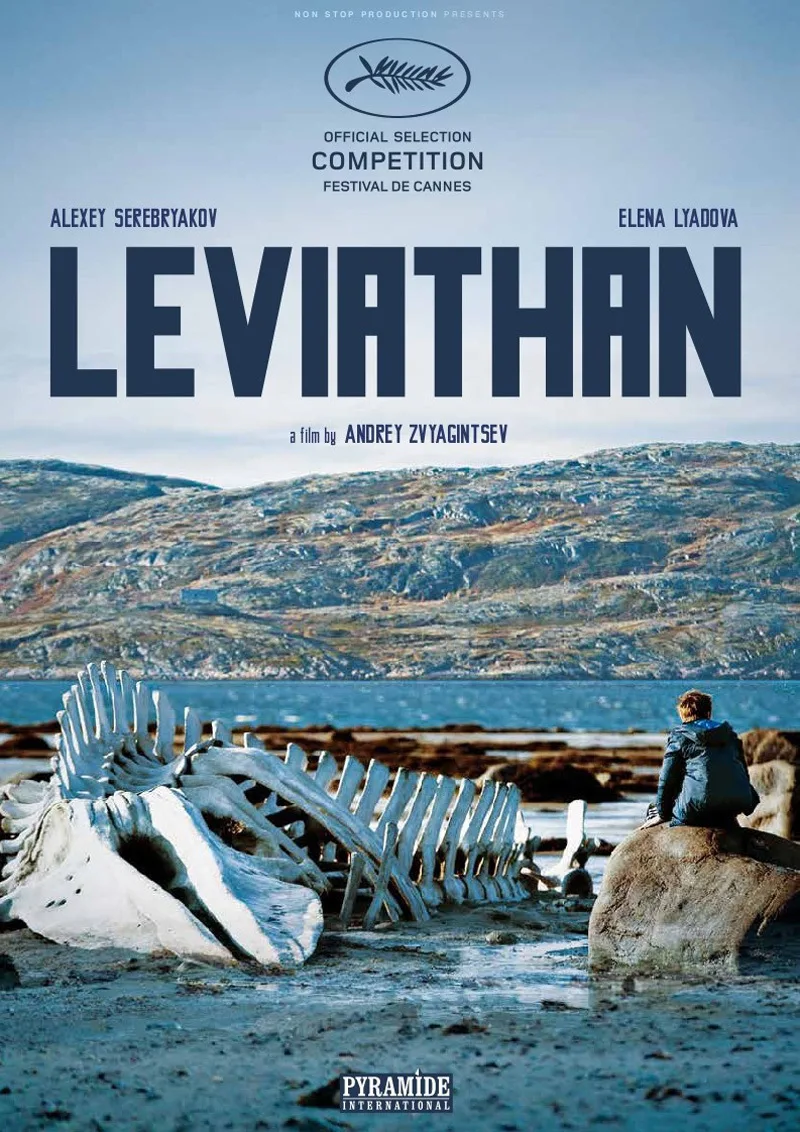

Though it takes place in a small town and involves only a handful of characters, the Russian drama “Leviathan” has a feeling of expansiveness, even grandeur. It opens with distant, monumental views of Russia’s north shore, where huge rock formations slope down into a churning, slate-gray sea, images set to a propulsive Phillip Glass score. Soon we see the husks of abandoned sea-faring vessels along the water’s edge, where, later in the film, we’ll behold the enormous skeleton of a beached whale – a leviathan evoking both the Book of Job and Thomas Hobbes’ famous political tract.

A prize winner at Cannes and Russia’s nominee for this year’s Best Foreign-Language Film Oscar, “Leviathan” is easily the most important and imposing film to emerge from Russia in recent years. Since its story conveys a sense of pervasive political corruption, it has been read as a daring and scathing critique of conditions in Vladimir Putin’s Russia, and it is certainly fascinating to contemplate on that level. Yet there’s much more to writer-director Andrey Zvyagintsev’s singular artistic vision than simple political allegorizing, as the hypnotic opening of “Leviathan” makes clear.

In a sense, the film takes us back to the first of Zvyagintsev’s four features, “The Return” (2003), which won the Golden Lion at Venice and became an international art-house hit. Both movies feature dramatic landscapes that almost function as an additional character. Yet geographic specificity has no importance here; we never learn where either story takes place. The locales may seem vividly real, but for Zvaginstsev they’re primarily mythic – crucibles for dramas of the Russian soul.

Both movies also feature Biblical references that have oblique political connotations. In “The Return,” about a gruff father who encounters his two teenage sons after an absence of 12 years, it’s the story of Abraham and Isaac, with the suggestion that the tale concerns the re-imposition of threatening paternalistic authority 12 years after the collapse of the Soviet Union. In “Leviathan,” the Book of Job references evoke timeless human suffering as well as the metaphysical questions it entails, while also pointing toward Hobbes’ notions of the freedoms that people surrender for the security of an authoritarian regime like Putin’s – a theme that obviously has implications for many countries besides Russia.

The invocation of the mythic and the Biblical along with related historical, philosophical and political ideas should indicate that much of the “drama” in a Zvyagintsev film lies in wrestling with its multi-leveled (potential) meanings. The dramas themselves are usually fairly simple and emotionally direct, though each has a core of mystery and ambiguity that not only invites but compels our interpretative engagement.

The main character in “Leviathan,” Kolya (Alexey Serebryakov), lives and works on a small but desirable piece of waterside property that the local mayor, Vadim (Roman Madyanov), covets and has claimed for the town. The story opens when an old army buddy of Kolya’s who’s now a slick Moscow lawyer, Dmitri (Vladimir Vdovitchenkov), arrives to help him fight for his land. Though Kolya loses again in court, which seems under Vadim’s thumb, Dmitri then goes to the mayor and presents him with a sheaf of incriminating documents he’s gathered. It’s blackmail of a sort but at first it seems to work. Apoplectic, Vadim agrees to cut a deal.

All of this happens in a context where there’s lots of vodka drinking, argumentation and simmering discontent of various sorts. Kolya’s moody teenage son by a previous marriage (Sergey Pokhodaev) can’t get along with his current wife, Lilya (Elena Lyadova), a pensive beauty who works in a fishery. Introducing Dmitri into the home ups the chances for both bonhomie and trouble. Meanwhile we see the almost constantly drunken Vadim consorting with a well-groomed priest, who tries to allay his political fears with religious platitudes.

The corrosive intertwining of politics and religion is a provocative theme in “Leviathan.” Thoroughly corrupt, Vadim belongs to a national hierarchy that, Zvyagintsev pointedly suggests, isn’t much different from the Communist one it replaced: indeed, while a statue of Lenin still stands in front of the courthouse, a glowering portrait of Putin looms over Vadim’s office. Yet today’s strongmen, rather than trying to eradicate religion, are bolstered by their mutually beneficial support of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Still, though he includes a brief reference to Pussy Riot, it wouldn’t be accurate to say that Zvyagintsev is anti-religious in any one-dimensional or atheistic sense. Like Andrei Tarkovsky before him, he’s a staunch anti-Communist who seeks to, in critic Oleg Sulkin’s words, “draw support from the archetypally Russian intellectual and spiritual tradition that was trampled by the Bolshevik regime.” Late in “Leviathan,” there’s scene with a humble local priest who is portrayed as a sympathetic, spiritual counterpoint to the gilded, officious prelates we see in the film’s climactic scene, where current Russia’s perverse symbiosis of church and state is anatomized to devastating effect.

Though the tone of most Zvyagintsev films might be described as brooding if not portentous, there’s also a degree of wit to his approach here. In one of the film’s most memorable scenes, Dmitri joins Kolya, two male friends and their wives and kids for an outing to the country to shoot guns and drink vodka. After one of the men destroys all of the bottles they’ve brought for target shooting with a blast of machine-gun fire, another produces an alternate set of targets – portraits of Soviet leaders from Lenin through Gorbachev. Asked if he’s got any of subsequent Russian leaders, he jokes, “It’s too early for the current ones.”

While this scene contains another of the haunting landscapes that Zvyagintsev is so adept at conjuring, it also illustrates his particular visual mastery. Indeed those portraits are a characteristic instance of symbolic iconography; the director often pauses to gaze at such ambient images, whether old photos or fading religious murals. More characteristic still is his elegant choreography of subtle camera movements, muted natural lighting (Michail Krichman’s cinematography is precise and understated throughout) and the comings and goings of several actors, all of them part of an ensemble that’s uniformly excellent.

Ultimately “Leviathan” may divide viewers between those who find its possible meanings too numerous and inchoate and others who welcome the challenges of helping create its meaning. Certainly, its prize-winning script can be faulted on a couple of levels: the motivations of Lilya, an important character, are left entirely opaque; and the attempt at a piercingly tragic conclusion doesn’t quite come off. Yet the film’s ambitions are so grand and multi-dimensional, and mostly accomplished, that Zvyagintsev’s audacity can only be applauded. His is a career that now must be counted one of the most significant in contemporary cinema.