Claude Chabrol calls his film about jealousy “L’Enfer,” French for the inferno of hell, and Paul, his hero, burns with a helpless flame during most of the story.

Paul is a man who can be pleasant, who looks normal and friendly, but who is going violently mad. That does not make him the ideal proprietor for the charming lakeside inn he buys and manages with the help of his new wife, Nelly. She is an almost extravagantly sexy young woman who is, he suspects, having affairs with every man in sight. He is wrong. Well, probably.

But first a word about Chabrol, who has made 47 films since 1958, almost every one of them worth seeing, some a great deal better than that. His subjects are often murder, passion and the ways the secret drives of his characters can lead them to actions they can hardly admit to themselves. In his masterpiece “L’Boucher” (1968), a school teacher falls in love with a butcher, who may be guilty of murder. Does she know that? Did he kill to impress her? Does she know that? The key figure in “L’Enfer” is Nelly, the wife. Paul is almost a hopeless case even from the first frames, sliding beyond jealousy into insanity. But what about her? Surely she knows how sick her husband is? He will misinterpret even the slightest hint of infidelity. Why, then, does she give him reason for suspicion? Is she actually cheating on him? We think not, but cannot be sure. Is she teasing him? Or is it . . . deeper still? Does she in some way link with his madness, and choose to share his doom? Does she foresee the end of the story, and conspire to bring it about, without even admitting that to herself? This reading makes sense of “L’Enfer” in a way that a more facile interpretation does not. Look at the surface of the movie, and its story of a man who is driven mad by jealousy, who makes life miserable for himself and everyone around him, and who is headed for tragedy, with his wife as a helpless bystander. That is not really a very interesting story. Not nearly as interesting as the possibility that Paul and Nelly are linked in a deep blood doom: that she is one of those persons drawn to another precisely because of danger.

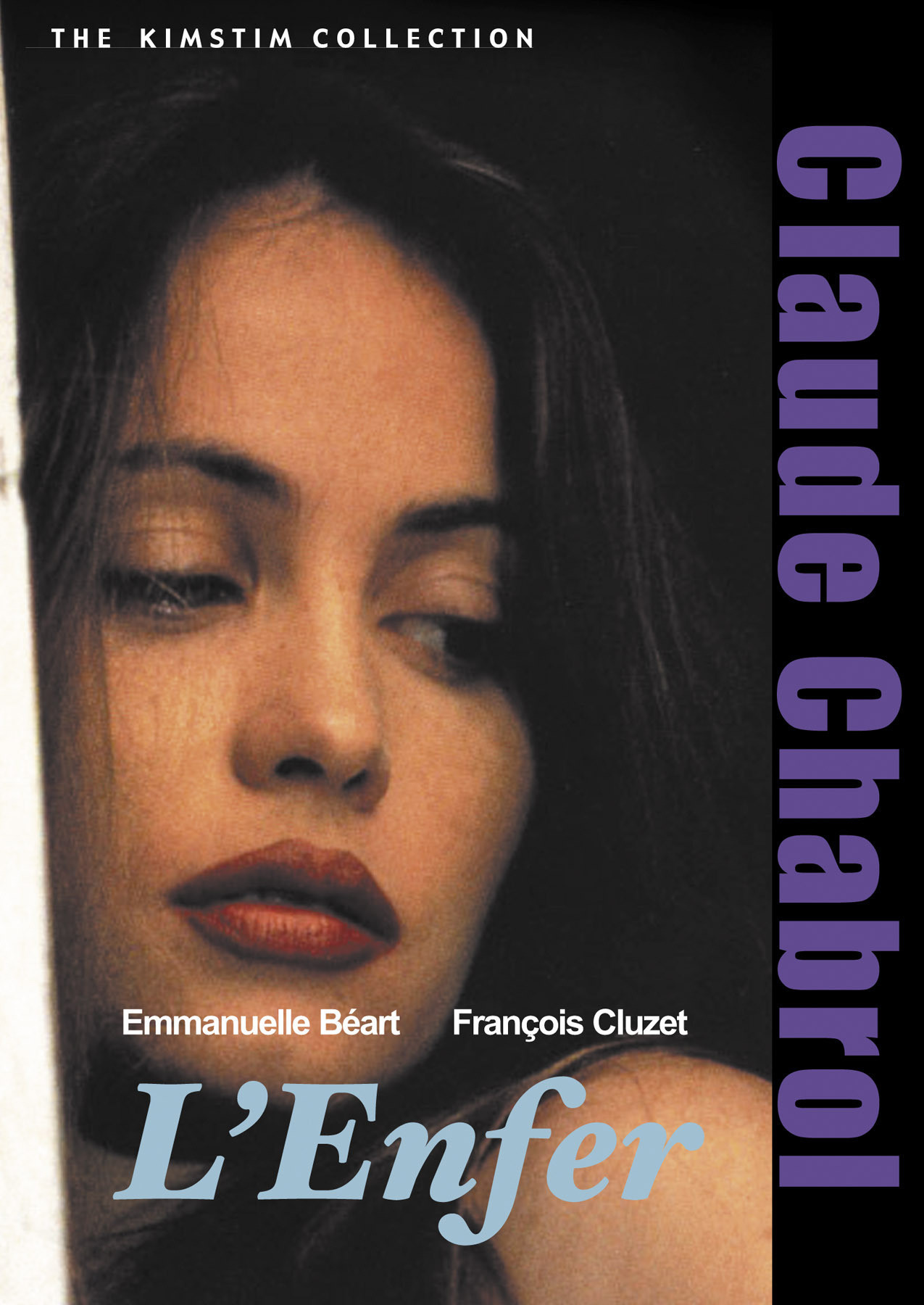

Nelly is played by Emmanuelle Beart, who was angelic in “Manon of the Spring” and engaged in covert sexual combat in “La Belle Noiseuse.” Here she has transformed herself, with lipstick a little too bold for her mouth, with provocative eye shadow, into a women who seems unable to control her sexuality.

Does Nelly not know the effect she has? What does she think in the morning when she paints her mouth? What is her motive? And where does she find those bras that shape her into a 1950s sweater girl? In the hands of another director, “L’Enfer” might have seemed pointless, since the ending is more or less preordained, and the action is hard to accept on a realistic level (Paul puts his poor guests through such a hell of their own that they seem like victims in a French “Fawlty Towers”).

But there is that other level. The way Nelly acts, and does not act. The way she toys with Paul. The way she doesn’t walk away when she should (for she is not the classical battered wife, and far from a captive). What is she up to? Watching the movie, we focus on Paul. Remembering it, we think of Nelly.