The Kray Brothers, Reggie and Ronnie, were such ostentatiously violent and vulgar gangsters that they practically constituted a self-parody. They were both newly in jail when the then-also-new comedy troupe Monty Python’s Flying Circus deemed to lampoon them with a sketch about “The Piranha Brothers,” Doug and Dinsdale, but the thing about that sketch, as it happened, was just how little it needed to stray from reality in order to hit the comic mark. Nevertheless, the Krays, who ruled criminal London from the late 1950s until their imprisonment in 1968, did real and wide-ranging human harm in their careers; this is a fact that Brian Helgeland, writer and director of a new crime movie about the twins, doesn’t seem to have any good ideas about what to do with. But that isn’t why “Legend” is such a muddle right off the bat.

Right off the bat it’s a muddle because of Helgeland’s slavish devotion to Martin Scorsese, a bad thing to display when you don’t have Scorsese’s chops. Early on in the picture, as Reggie Kray, the relatively charming, less psychotically violent of the fellows, is courting his future wife Frances, Helgeland opts to do a little “GoodFellas.” As Reggie escorts Frances into a pub where he’s the kingpin, the moving camera follows from behind and glides alongside the couple as various friends of Reggie pay their respects. On a stage at the back, a singer is crooning “The Look of Love,” a song that had not actually been written when the scene takes place, but never mind that. You know where this is going. Helgeland wants to create his own version of the famed Copacabana tracking shot in Scorsese’s legendary 1990 gangster film, but he hasn’t quite worked out all the choreography—hence, the aforementioned singer ends up performing the world’s longest version of “The Look of Love,” at least until the point at which the sound editor or someone decided to have mercy and faded the guy out and substituted some generic-sounding movie music. This is merely one example, and a pretty outstanding one. There are plenty more throughout the film. (All of this is doubly stupefying when one recalls what a solid job Helgeland did in both writing and directing departments in his last picture, the 2013 Jackie Robinson story “42.”)

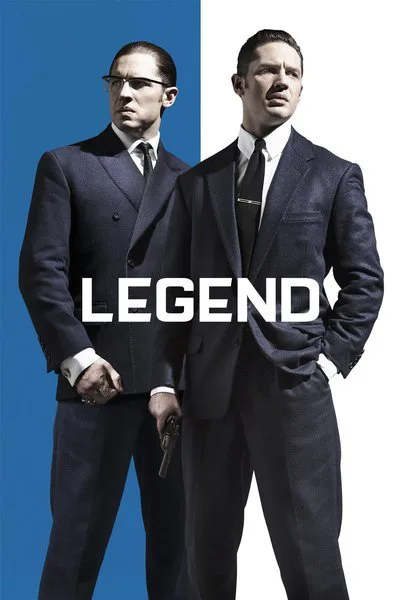

The movie’s main advantage and/or talking point is Tom Hardy, who plays both twins. Reggie is slick and confident, while Ronnie, a paranoid schizophrenic with strong sadistic tendencies, is like Lenny in “Of Mice And Men” if Lenny had been an East London mook, and evil to boot. Both performances are commanding, but not as commanding as they might have been. The weaknesses of Helgeland’s writing and directing are also to blame here. Particularly the latter: the unimaginative (and, I imagine, practically expedient) framing of the two Hardys during scenes in which they’re together makes the dual performance play like a tricksy stunt at times. Helgeland could have learned a great deal from the blocking of dual Jeremy Irons accomplished by David Cronenberg in “Dead Ringers,” which made the viewer feel as if there were really two different people in the frame. Too many times here there’s the feel of two different performances. Sometimes Hardy manages to ignite a spark. There’s a scene in which Chazz Palmentieri, playing a bluff emissary from the American Mafia, makes the twins an offer they’re better off not refusing, Ronnie’s belligerence notwithstanding. When Ronnie makes an unabashed announcement concerning his sexual preferences to this wise guy, it’s a real moment. As is one with Hardy’s Reggie, finally confessing at the end to his brother why he’s directing his own violent impulses so destructively into one target.

Moments such as these are too few and far between, while moments such as a wedding scene prefaced by the song “Chapel of Love” are far too many. The lucky bride is Reggie’s, and her name is Frances, and it’s with Frances’ story that the movie, for me, broke away from irritating mediocrity and into genuine badness.

Helgeland’s conception of Frances is doubly banal. First, he saddles her with the burden of semi-omniscient narration that’s rife with platitudinous nonsense (“It was time for the Krays to enter the secret history of the 1960s” and “Not even Scotland Yard could ignore murder on the street,” the latter of which has the uncomfortable echo of the bit in the Piranha Brothers sketch wherein the gangsters detonate a nuclear device over London). Second, he gives her onscreen character hardly any more depth than any of the complaining gangster and/or undercover cop wives you’ve seen in dozens of crime pictures over the years, Emily Browning’s committed performance notwithstanding. Which makes Helgeland’s final trick with this character all the more objectionable when he finally pulls it. I knew a bit about the case of the Krays before coming in to the screening of the picture, but that knowledge wasn’t at the forefront of my consciousness as I watched the movie. And then I thought … wait a minute. And sure enough …

Spoiler alert: Reginald Kray’s real-life first wife, Frances Shea, committed suicide in 1967, two years after marrying Kray. And this is indeed depicted in the last fifth of the film, complete with Frances-as-narrator playing a little bit of “gotcha” with the audience. It strikes me as both aesthetically cheap and morally dubious to make an actual suicide into your own Joe Gillis for the sake of … well, that’s the other thing, which is I don’t know what “Legend” was made in the sake of. It’s a squalid story told with very little in the way of a dynamic personal perspective, and hence a waste of its very talented cast.