First things first, although I know this won’t matter to the people mounting a campaign against this project: a film is not a trial. It is not a place where there’s a legal requirement for cross-examination or demand for a burden of proof. Every documentary comes from a perspective, even the ones that don’t make that perspective blatantly clear. It is not a critic’s or film goer’s role to investigate the facts presented in a documentary. There are journalists for that (and there have already been some great pieces from that angle about the allegations contained within this movie). Sure, you can question the testimonies presented in a film and the filmmaker’s perspective, and sometimes you should. But, as to this case, let’s stop pretending that we haven’t heard over and over again from Michael Jackson’s camp about the claims that those who have accused him of sexual abuse of boys are just money-hungry liars. Jackson and his fans have made that stance clear over and over again, and, of course, it’s worth noting that he’s been acquitted by our legal system. This film doesn’t stop that from being true. However, again, a film is not a trial, and “Leaving Neverland,” the controversial 4-hour documentary about two of his accusers, is a powerful demand to listen to the other side too. It’s not an easy listen. But, as we’re learning more and more with cases of abusive predators, we need to listen more carefully because the abuser often has the power and platform to yell louder. At its best, “Leaving Neverland” tries to balance the volume.

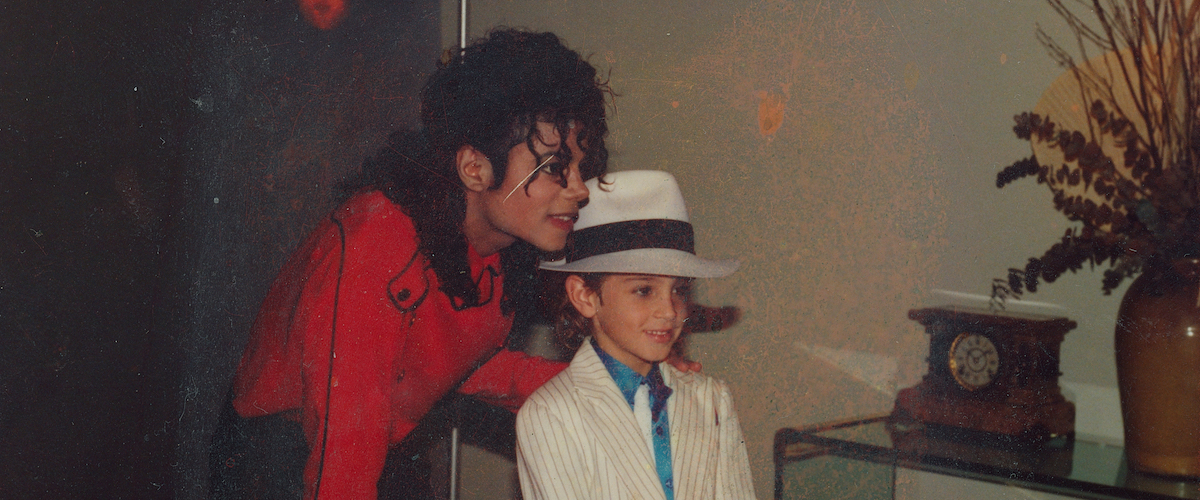

“Leaving Neverland” focuses with laser intent on two men and their families: Wade Robson and James Safechuck. Both men speak candidly and explicitly, and their stories form the entirety of the nearly 240 minutes of “Leaving Neverland.” We only hear from the men and their families, including the mothers who now feel so much guilt about what happened and their wives who were there after Michael’s death when the truth finally came out. We only hear Michael’s voice in archival footage from news reports and home videos shot by the boys or messages MJ left for them. It’s important to note that this is not Michael’s story. There’s no biopic material about the Jackson 5 or extended concert footage. We don’t seek to find who Michael was beyond his relationship with these two boys, one of whom he allegedly started having sexual relationship with at the age of 7.

“In Paris, he introduced me to masturbation, and that’s how it started.” That allegation comes 38 minutes in, and it’s only the first of dozens of incidents recounted by Safechuck and Robson. Hidden rooms at Neverland, drills they would run to get dressed as fast as possible without making noise, the way Jackson would poison the boys against their families while also wooing the families to keep his victims in his life—around 75 minutes in, after a story about oral sex and a seven-year-old, I had to do something I try to avoid when I’m watching something for review: I needed a break. I could feel my skin crawling. I was just drained by the horror of it all, a physical and emotional breakdown likely enhanced by the fact that I have three sons under ten myself. The stories of Jackson’s abuse in “Leaving Neverland” are unrelenting, sometimes hesitantly but also courageously recounted by the people who claim to have lived them.

The main talking point that MJ’s defenders seem to try to discredit the film with is that Robson testified on Jackson’s behalf at his last trial, claiming that nothing had ever happened. Not only does completely denying that he could have been lying on the stand indicate a lack of understanding as to how commonly people repress child abuse, but both Safechuck and Robson are open about another element of their stories: they loved Michael Jackson. He had them convinced that the sexual abuse was a part of that love. When they were abused, they didn’t even see it as abuse. Even into adulthood, they had great love for the man, and they speak of him like adults speak of a formative relationship that broke up. Michael Jackson brought Wade Robson to the United States from Australia and helped make him a superstar. It wasn’t until the boys turned into men and had boys of their own that the repressed trauma rose to the surface.

“Leaving Neverland” isn’t a perfect film. There are too many drone shots of L.A. and over-use of score by director Dan Reed. It’s also hard to avoid the feeling that there’s an even stronger version of this that runs a traditional feature-length. Although one can imagine Reed asking himself what he could possibly cut from these men’s confessionals. After all, “Leaving Neverland” is about listening to their sides of the story. You don’t have to believe them (although I do). Listening to these men unleash their pain doesn’t change a note of Michael Jackson’s music and clearly won’t change the minds of those who seem to make a living off defending him. As Robson’s sister says, “I’m not taking anything from Michael’s talent as a superstar, but, as a man, as a human being, he’s hurt people. And those people that he’s hurt should have a chance to talk about it and they should be allowed to be OK.” It’s impossible to argue with her.