The low-budget, idea-driven corner of science fiction has become a crowded place recently. “Lapsis” is the latest entry worth seeing and arguing about. Written, directed, edited, and scored by Noah Hutton, and shot (by Mike Gomes) on location in New York City and in forests upstate, this is a rare American feature that not only dares to be a satire, but masters the subtle fluctuations in tone that satire needs. Focusing on a luggage deliveryman who gets pulled into a global digital ponzi scheme, the movie envisions a desperate “New Economy” like ours, but with details changed. Then it keeps us chuckling at the believable absurdity of it all, even as its characters are exploited and abused and try to fight back.

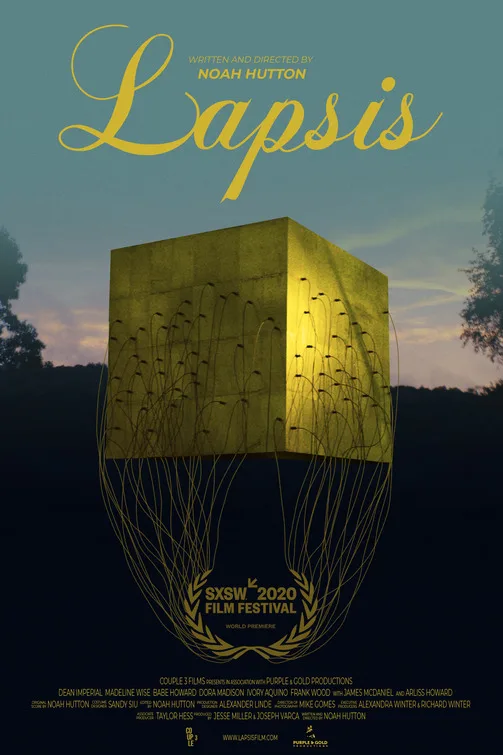

Dean Imperial plays Ray Micelli, a working class Queens man who quits his baggage delivery job and starts working for CABLR, a global company that hires people to walk through depopulated areas, unspool lengths of cable, and plug them into giant black cubes. CABLR is affiliated with Quantum, a tech company on the verge of claiming a global monopoly of hardware and software. Apparently the cables are needed to connect Quantum servers to each other and to Quantum’s devices.

What are these companies up to? Hutton doesn’t get too deep into the details. This is a “McGuffin” script that takes its cues from David Mamet screenplays where desperate individuals chase after The Leads or The Process or The Case. What’s important is that CABL promises economically desperate people a pathway to “success.” Go forth, Americans, the company’s videos exhort, and drag spools of cable through a forest, and if you maintain a certain pace and hit certain marks by certain times of day, you’ll get a better route and more money next time.

Ray needs a cash infusion because his kid brother Jamie (Babe Wise) needs medical treatment for Omnia. That’s like Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (which the brothers’ mom died of) but worse. A neighborhood character named Felix (James McDaniel) offers to sell Ray a “medallion” that he needs to work for CABLR (like the taxicab medallions that drivers buy from city governments). But there’s a catch: this medallion is still in the system but inactive, and to possess it, Ray must promise to give Felix and his associates thirty percent of whatever he makes.

Then Ray has to go into the Allegheny mountains and lay miles of cable, which won’t be easy because (a) he’s a first-timer competing against people with much more experience, and (b) the job requires him to hustle through woods for days on end, going up and down hills and sleeping in tents, and Ray is a soft-bellied, middle-aged man who looks as if his main form of exercise is raising a beer can to and from his mouth; and (c) each participant is shadowed by a robot that look like a cross between a dog and a tiny coffin, and if it beats them en route to the next cube, their pay is docked and better opportunities are withdrawn.

The filmmaker does a phenomenal job of setting up this world in a natural-seeming way, smuggling mountains of pertinent fact into conversations that pretend to be banal. Notice, for instance, the long scene between Ray and Felix in a neighborhood coffee shop—a Christopher Nolan-level info dump that feels organic because of how it’s written and performed: just a couple of guys blabbing over lunch. Once Ray gets into the woods, Hutton repeats this trick in conversations between Ray and other CABLRs (including Madeline Wise’s Anna, a labor activist trying to unionize the workers). Because Ray is new to the terrain as well as the job, it makes sense that he’d ask so many questions.

It’s a clever storytelling trick that’s perfect for the film as well as for its leading man. Imperial is a 1970s style character actor/lead who has some of the beefy neurotic Everyman energy that Philip Seymour Hoffman and James Gandolfini used to radiate in their indie film projects. We learn and grow (and grow angrier) with Ray as the extent of the corporation’s evil comes into sharper focus, and the actor lets us feel Ray’s moral and political awakening rather than constantly indicating it.

The CABLR processes have been fully imagined as well. Hutton draws on news reports about the blandly sinister expansionism of Google (there’s an equivalent of Google’s absurd-in-retrospect “Don’t be evil” mantra) as well as Amazon’s exploitation of drivers and warehouse workers (CABLRs carry handheld devices that chirp at them to “challenge your status quo!” and warn them that they’re going off-route or that they shouldn’t stop because they haven’t “earned a rest” yet). Spidery drones soar or hover overhead, watching workers’ progress and getting ready to drop replacement cable or fresh droids. I’m guessing that we’re five years away from all this stuff being common. Oh, hold on, there’s a robot at my door, I’ll be right back.

Unfortunately, even as “Lapsis” exceeds your wildest expectations for low-budget sci-fi world building, it doesn’t do as much with those details as one might wish. There’s a conspiracy wrapped inside of all the enigmatic rushing-around, and when that stuff moves to the center of the story (two-thirds of the way through the film’s compact 105-minute running time) a bit of the specialness leaks out of the project. This is partly due to the fact that the main characters finally exercise some agency and begin to seem like more typical studio-level science fiction characters who are on the brink of exposing the truth, sticking it to The Man, effecting real change, etc, even though by that point “Lapsis” has done such an outstanding job of cultivating a Kafka-eque or “Brazil“-like sense of grinding yet hilarious despair that it feels weird and false when we’re not in that headspace any longer. It’s as if somebody had sculpted a perfect death’s head mask, then turned the corners of the mouth up with a Sharpie.

Still: what a debut! If you made a Venn diagram of influences that included Ken Loach working-class-rage pictures like “Sorry We Missed You” or “I, Daniel Blake,” Boots Riley’s “Sorry to Bother You,” Alex Cox’s “Repo Man,” and Mike Judge’s “Office Space,” “Lapsis” would land smack-dab in the middle. That’s a hell of a great spot for a first time feature to be in. No wonder it doesn’t know what to do with itself.