Marco Ferreri’s “La Grande Bouffe” is to gastronomy as “The Exorcist” is to “Song of Bernadette,” which is to say eat before you go, you won’t be hungry afterward. It’s the story of four friends who gather for a weekend of eating and wenching that gradually reveals itself as a suicide pact. They eat themselves to death. And not metaphorically; no, they eat themselves to death literally before our very eyes, and not a morsel of the feast goes undocumented.

In a way, the movie works like “The Iceman Cometh.” After four hours trapped in Eugene O’Neill’s run-down Irish saloon with a menagerie of defeated alcoholics, we don’t exactly rush out for a drink. Only “The Iceman Cometh” had a humanistic substructure, and something to say about its characters; “La Grande Bouffe,” as nearly as I can tell, is essentially just a chronicle of gluttony and self-hate.

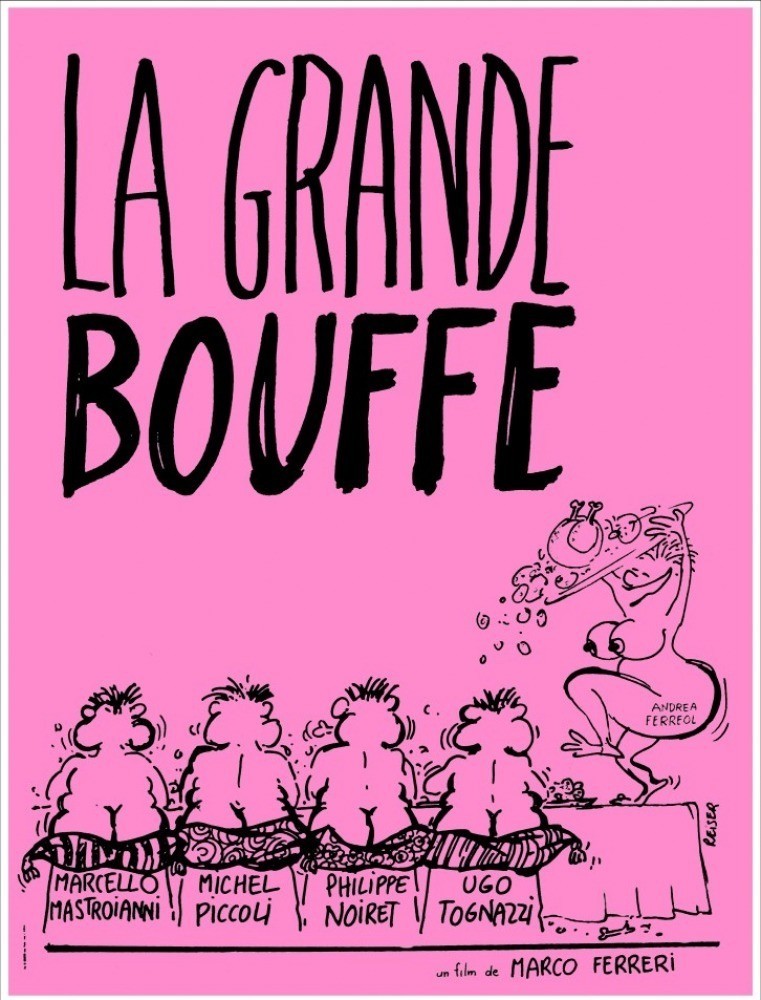

I say as nearly as I can tell, because the movie arrived here after creating the cinematic sensation of its year in France. It opened at the Cannes Film Festival attended by gleeful controversy; the critics chose up sides and attacked it as either (a) the most disgusting and decadent film in the history of France or (b) a savage, radical attack on the bourgeois establishment.

Catherine Deneuve went to see it with her lover at the time, Marcello Mastroianni (who is one of its stars) and would not speak to him for a week afterward, or so it is said. When you are Deneuve and Mastroianni, however, perhaps there is little need to speak. In any event, the movie went on to become (according to the publicity) the largest-grossing release in the history of Paris, all the while inspiring fistfights and insults on the Champs Elysees.

I give you this background in order to be fair, because “La Grande Bouffe” didn’t leave me so much excited as exhausted. There is no doubt great significance in the way the characters talk about themselves, each other and French society; there is a double-reverse message to be found, I suppose, in the utter contempt with which the prostitutes in the movie are treated. The sight of bourgeoise pigs being pigs is no doubt, from a certain point of view, an attack on their pigginess.

Those would be the things the French intellectuals would argue about, but for me the film was more of an experience than a treatise; like “The Exorcist,” it doesn’t have philosophical depth when you think about it, but in the theater it hammers your sensibilities. It’s decadent, self-loathing, cynical and frequently obscene. But there’s one thing you can say for it (and my colleague Terry Curtis Fox did, on his way out of the theater): “This film reaffirms my faith that it is still possible to be offended by a film.”