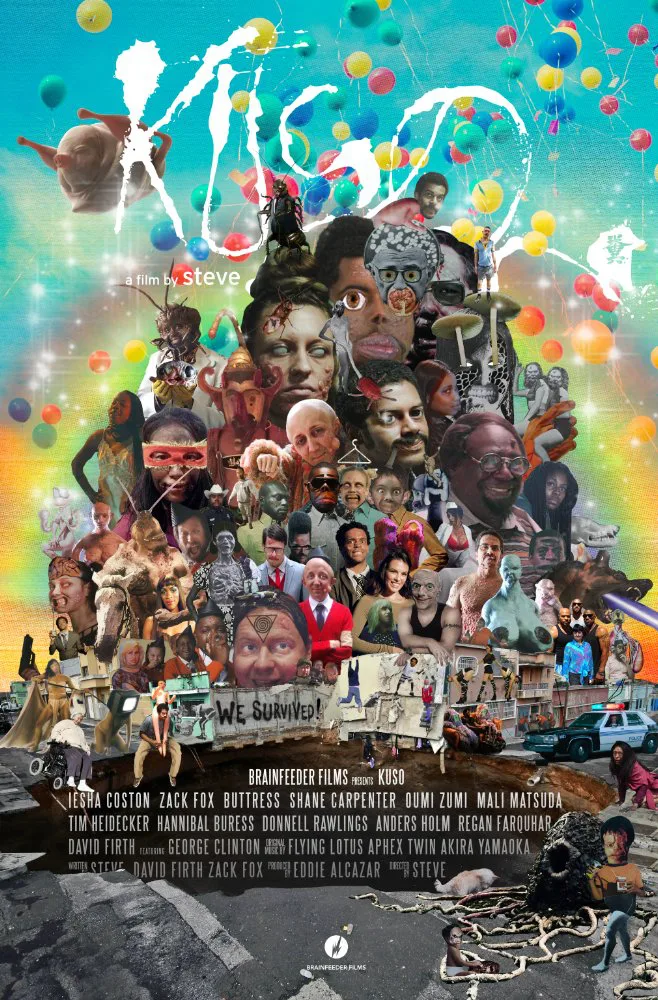

“Kuso,” a trippy collection of surreal comedy sketches, feels like a variety show from another planet. It’s a noisy, lumpy collection of gross stuff that is vaguely thematically related, but only by stream-of-conscious logic. This presents a problem: how seriously should we take such a puzzling, fitfully fascinating collection of barely developed ideas, many of which center on bodily fluids, human waste, and rotting body parts? Written, scored and directed by formidable hip-hop artist Flying Lotus (AKA: Steve Ellison), “Kuso” is too proudly low-brow to be art gallery material. But you can see a level of consideration and personality here that sometimes puts this film leagues ahead of anything that’s being done by contemporary post-dada pop surrealists like Tim Heidecker, Eric Wareheim, Eric Andre, and many other stoner-friendly comedians who regularly crank out bizarro outsider art for Cartoon Network’s late-night Adult Swim off-shoot. “Kuso” may often feel unproductively loud, and monotonous, but it is a head-scratcher worth contending with.

Produced over the course of two-and-a-half years, “Kuso” is a roiling stew of Flying Lotus’s creative influences, some of whom have cameos in the film, like Heidecker and Funkadelic/Parliament co-founder George Clinton. All the events you see are somehow precipitated by a catastrophic Los Angeles earthquake. Beyond that, the only thing holding these scenes together are Ellison’s recurring fixations with scab-and-pustule-encrusted nebbishes, and insects that emerge from rectal orifices. Watching “Kuso” consequently feels like an excavation of the many subterranean chambers of Ellison’s anally-fixated imagination.

A bald child with facial deformities eats and prays with his grotesque mother, then ventures into the woods and rubs his own waste on the mysterious creature that inhabits a mossy knoll that looks like a gaping anus. Click. A Japanese woman tumbles down a hole, and discovers herself in a hellish underworld where her legs are somehow attached to a stranger’s limbs. Click. A marijuana-addled woman puzzles over news that she’s pregnant and fends off advances from two inter-dimensional alien roommates who look like sentient shag carpets. Click. A red computer-generated steam of what looks like bloody diarrhea hangs and undulates in the air. Click. Paper cut-outs and computer-generated images of Hieronymous-Bosch-like hellscapes are nested within human heads trapped in eyeballs trapped in skulls trapped in mouths. Click. A musician, played by Ellison, tries to banish his irrational fear of mammaries by having Clinton, playing a holistic doctor named Dr. Clinton, have a bug that lives inside Clinton’s posterior spray him with psychedelic excrement. Cl–

Wait, what was that last one?

Your brain struggles to make connections between these segments because each subplot is broken down into three -to five episodes each, cut up, and spread out over the course of the film. But the diced-up juxtaposition of these segments necessarily prevents them from gelling together, so they never cohere into a bigger picture. I can commend Ellison for singular set pieces, like the film’s inspired opening musical number, or a weirdly intimate early sex scene. I could also lament dismal gags, like anything involving Heidecker, a blow-up doll, and aliens.

I could also rattle off any number of Ellison’s salient influences, like Clinton, H.R. Giger, William Burroughs, David Cronenberg, Marcel Duchamp, Crispin Glover, Danny Elfman, Alejandro Jodorowsky, and Monty Python. Or I could make comparisons to Clinton’s “Cosmic Slop, Oingo Boingo’s “Forbidden Zone,” or Kool Keith’s “Dr. Octagonecologist.”

But the main thing about “Kuso” is that it feels like a deliberate attempt at frustrating your ability to make connections. Characters smear their waste on each other’s faces. They don’t make eye contact, and often talk past each other. Semen, pus, and feces are everywhere, and everybody inevitably retreats or teases open the gateway to the next freaky sub-conscious sub-basement. It’s like a giant counter-culture ouroboros, except there’s nothing seamless about this freaky self-devouring nightmare.

In that sense, “Kuso” feels most important as a declaration of Ellison’s arrival as a new voice in filmmaking. It definitely reads like a first film: full of promise, but oh so labored, and fussy. Ellison’s music doesn’t seem nearly so disjointed, and it appears that a change in media has resulted in some awkward first steps. Then again, maybe the best way to look at “Kuso” is a product of apparent creative labor that only really works when Ellison stops telling us what type of art he likes, and starts trying to do something with his pet influences. I can’t wait to see his next film. Hopefully by that point he’ll unclench, and just do what comes naturally.