While Cormac McCarthy fans have been waiting decades for an adaptation of his 1985 epic Blood Meridian, first-time filmmaker Ned Crowley’s “Killing Faith” feels indebted to it in ways that help elevate it beyond its modest budget and aims. Like that novel, and so many of the anti-Westerns it follows (“3:10 to Yuma,” “True Grit”), Crowley’s film sets itself in a brutal vision of the Old West festering with the stench of man’s evil and violence, one so foul that it wafts into the realm of the supernatural. In fact, it even touches on more macabre takes on the Western, such as S. Craig Zahler’s “Bone Tomahawk” and Antonia Bird’s remarkable “Ravenous”—both films that posit the frontier as a place where those who trespass upon it are justifiably punished.

Crowley settles us quickly into the movie’s grim tone when, in his opening shot, the hazy plains of the Old West (gorgeously captured with ambered, shallow-focus photography by DP Justin Hamilton) push out to reveal the bloodied hands of a doomed desperado shuffling a deck of cards. After a failed attempt to kill the bounty hunters who have him caged, the desperado begs God for mercy. “It ain’t God you got riled up,” responds his captor before putting a bullet in his brain. “It’s worse.”

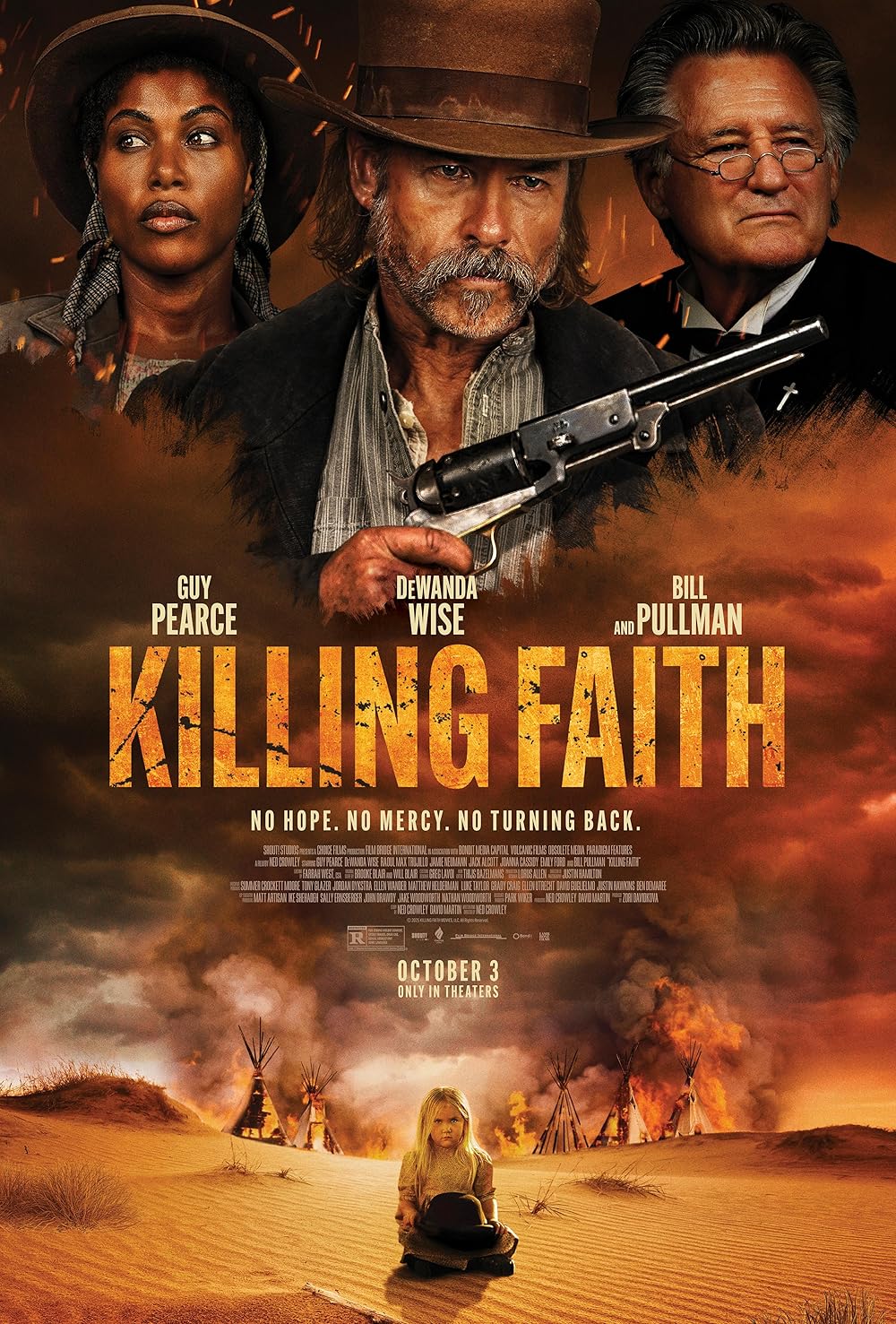

From there, we learn that it’s 1849 and a “sickness” has been spreading throughout the land; people are distrustful and paranoid, doubly so in the one-horse town where Sarah (DeWanda Wise), a freed slave, is trying to raise her white child (Emily Ford), the product of rape by a white sheriff, who carries the mysterious power to kill anything she touches. Out of options, and with the townspeople breathing down their neck, she enlists the aid of Dr. Bender (Guy Pearce), a pragmatic and cynical healer whose own past tragedies leave him breathing ether every night to go to sleep, to escort them and their simple, young helper Edward (Jack Alcott), to a faraway town. There, it’s hoped, a famed preacher named Ross (Bill Pullman) might be able to exorcise whatever demons lie within the young girl.

The journey there befits less the kind of grand, John Ford-esque odyssey you might infer than it does the kind of episodic encounters with the strange denizens of the West you might expect out of the Coens’ “True Grit” or Jim Jarmusch’s “Dead Man.” Indeed, Crowley’s film evinces that latter film’s strain of curiously dark humor; the people they meet along the way are dangerous, curious creatures, from an ominous itinerant family led by an eerie Joanna Cassidy (including a mute, guitar-playing brute with a burlap sack over his head, as if Leatherface played the Grand Olde Opry) to an erudite Native American hunter with a British accent who calls himself William Shakespeare (Raoul Trujillo). Some are guides, some are dangers, and “Killing Faith” delights in torturing our characters by not revealing which is which.

Crowley also passes our heroes through some of the most fascinating nightmare imagery a Western has presented in some time. Bender’s ether dreams include his dead daughter lying in a bed in the middle of the desert; characters vomit thick, black, gooey substances; dismembered bodies are arranged in sick tableaus where extremities aren’t where they’re supposed to be. Teepees on fire, murdered characters with their severed hearts placed in their hands. There’s a feeling of the dangers of taming a frontier that ought not be interfered with, as if Western expansion (the film does take place the same year as the Gold Rush, after all) awakens something ungodly and beyond the white man’s ken.

This reflects in our cast of marginalized outcasts; Pearce, fresh off his “Brutalist” Oscar nomination, always feels at ease in these kinds of troubled Western roles, and brings a fitting anguish to his skeptical, spiritually vacant doctor. He’s a man hardened by loss and his own complicity in it, who begrudgingly sees redemption in the quest that’s been laid before him. (A late scene leaves him, ironically for Pearce, chained like Prometheus to a stone, punished for his defiance.) Wise, as second lead, offers some much-needed glimmers of the kind of strength and resolve a Black woman of this time would have to muster to survive, much less thrive, even after her indentured servitude has ended. Pullman, though he arrives late in the film, makes a stark impression as a man who straddles both science and faith, seeing the child as a sign of man’s ultimate evil and seeking to vanquish it at any cost.

“Killing Faith” occasionally tips its hand towards its modest budget; gunshots and blood spurts look like cheap After Effects plugins, and some of the set decoration feels a bit sparse to build out the hard-scrabble world of the West. Its final act, as well, teeters a bit too earnestly into formula and contrivance for an oater as weird as this. But these minor sins are easy to forgive for such a bold, idiosyncratic anti-Western as this, the kind we don’t often get. It’s a work that positions the West as a place of damnation, testing even the most virtuous among us in ways that either break us down or strengthen our resolve. The evil that men do, a character says near the end, “tethers us to proof of the divine.” That Crowley packages these ideas in such a bleak, bloody curiosity as this is something to celebrate.