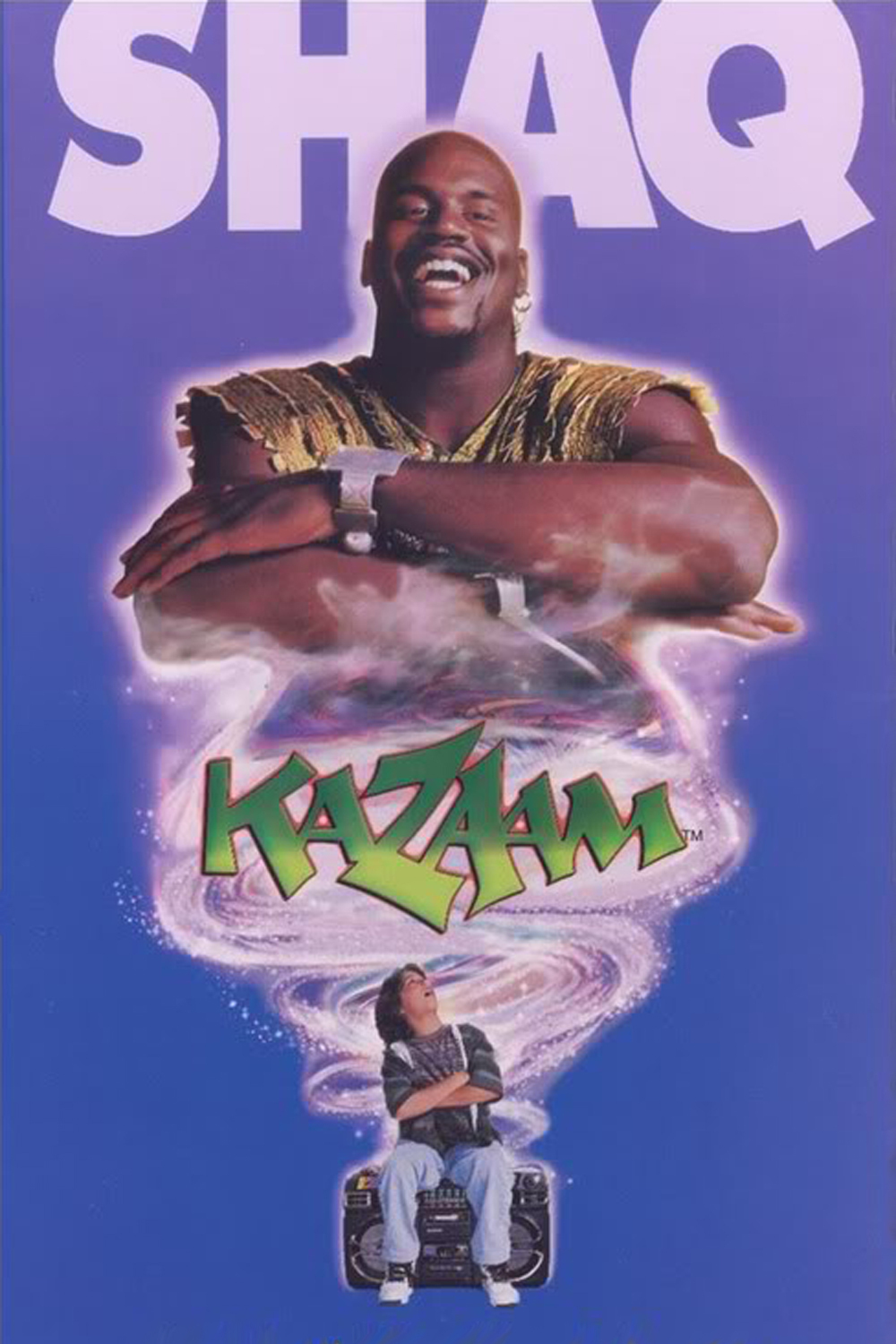

“Kazaam” is a textbook example of a filmed deal, in which adults assemble a package that reflects their own interests and try to sell it to kids. How else to explain a children’s movie where the villains are trying to steal a bootleg recording so they can sell pirated copies of it? What do kids know, or care, about that? The movie stars Shaquille O'Neal, the Orlando Magic’s superstar center, as Kazaam, a genie who is released from captivity in an old boom box and has to perform three wishes for a little kid (Francis Capra). Right there you have a wonderful illustration of the movie’s creative bankruptcy. Assigned to construct a starring vehicle for Shaq, the filmmakers looked at him, saw a tall bald black man, and said, “Hey, he can be a genie!” At which point, somebody should have said, “OK, that’s level one. Now let’s take it to level three.” Shaq has already proven he can act (in “Blue Chips,” the 1994 movie about college basketball). Here he shows he can be likable in a children’s movie. What he does not show is good judgment in his choice of material. This is a tired concept, written by the numbers. Kids old enough to know about Shaq as a basketball star will be too old to enjoy the movie. Younger kids won’t find much to engage them. And O’Neal shouldn’t have used the movie to promote his own career as a rap artist; the soundtrack sounds less like music to entertain kids than like a trial run for a Shaq album.

The plot: A wrecking ball destroys an old building, releasing a genie who is discovered by a kid named Max (Capra). He gets three wishes. The twist is, the genie doesn’t much like people, having made no friends in 5,000 years and having spent most of that time cooped up in bottles, lamps, radiators, etc. The other twist is, the kid doesn’t much trust people, because his father has disappeared.

The genie, however, helps the kid find his father, only to find out the father is involved in an illegal music pirating operation. The father is not quite ready to go straight, but after some action sequences involving an evil gang, he realizes his future depends on living up to his son’s expectations.

Uncanny how much this plot resembles “Aladdin and the King of Thieves,” a Disney made-for-video production set for release next month. In that one, Aladdin has never known his father, but an oracle in an old lamp tells him where the father is to be found, and the blue genie helps him go there. His father is the King of the Thieves, it turns out, and may not be entirely ready to go straight. But after some action sequences involving the evil gang of thieves, the father realizes that he must live up to his son’s expectations, etc.

Did anybody at Disney notice they were making the same movie twice, once as animation, once as live action? Hard to say. The animated movie at least has the benefit of material that fits the genre, much better songs, a colorful graphic style, and another outing for the transmogrifying genie with the voice of Robin Williams.

“Kazaam,” however, by being live action, makes the bad guys too real for the fantasy to work, and the action sequence feels just like the end of every other formula movie where the third act is replaced by fires and fights.

There are several moments in the movie when fantasy and reality collide. One comes when the genie astonishes the kid with a room full of candy, which cascades out of thin air. I was astonished, too. Astonished that this genie who had been bottled up for most of the last 5,000 years would supply modern off-the- shelf candy in its highly visible commercial wrappers: M&Ms, etc. Does the genie’s magic create the wrappers along with the candy, or does the genie buy the candy at wholesale before rematerializing it? There is also the awkwardness of the relationship between the genie and the kid, caused by the need to make Kazaam not only a fantasy figure, but also a contemporary pal who can advise the kid, steer him straight and get involved in the action at the end. Genies are fun in the movies only if you define and limit their powers.

That should have been obvious, but the filmmakers didn’t care to extend themselves beyond the obvious commercial possibilities of their first dim idea. As for Shaquille O’Neal, given his own three wishes the next time, he should go for a script, a director and an interesting character.