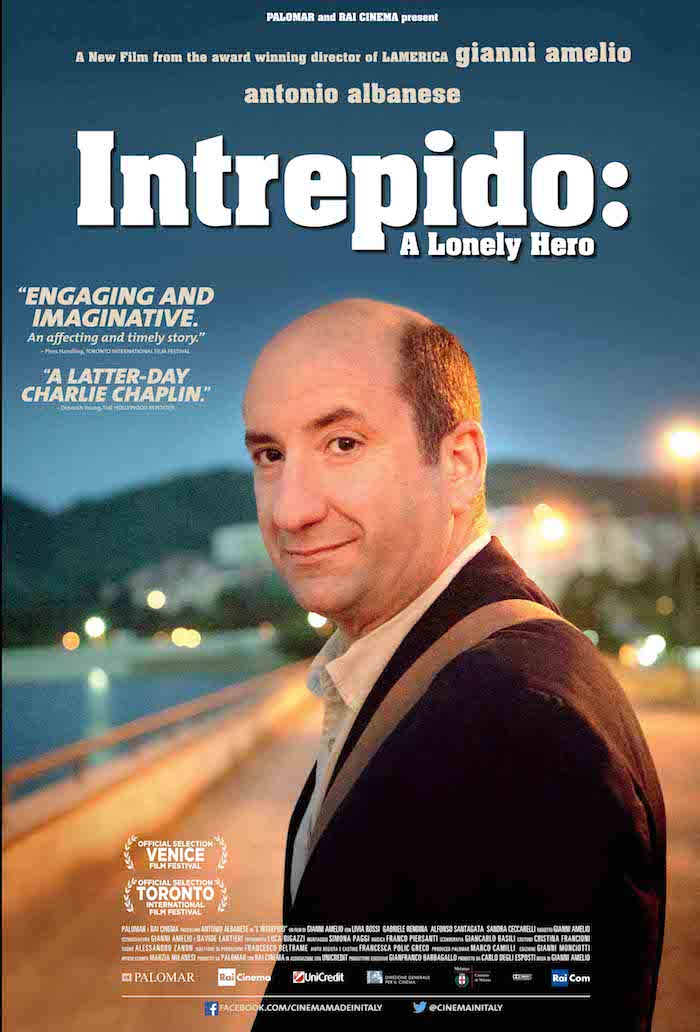

“Intrepido: A Lonely Hero” is a strange little film, and it’s likely to be considered so both by viewers who know and those who don’t know the work of Gianni Amelio. For those unfamiliar with the Italian auteur’s career, it might seem odd that an American distributor would import this lumpy, unaffecting tale of a Milanese Everyman who substitutes for other workers in an endless series of menial jobs. For viewers aware of Amelio masterworks such as “Open Doors,” “Stolen Children” and “Lamerica,” on the other hand, the puzzlement will lie in wondering how the creator of those magisterial films would end up turning out this curious trifle.

In the film’s opening minutes, we see Antonio Pane (Antonio Albanese) wearing a hard hat while working on a Milan high-rise construction site, where there’s talk of immigrant labor and the ineffectualness of unions. That’s the morning. By afternoon, Antonio is wearing a lion costume and trying to entertain spoiled kids at a shopping mall. Come evening, he’s pasting posters on billboards and being threatened by thuggish competitors.

Multiple jobs in one day? What gives?

We soon learn: Antonio is a “fill-in.” He fills in for workers who for any reason can’t perform their jobs. As we see him move from one task to another, in what’s obviously a thankless routine, it gradually emerges that he has only two significant relationships, and there’s a degree of trouble on both fronts.

The person closest to him is his son Ivo (Gabriele Rendina), a jazz saxophonist. Ivo regularly visits Antonio and takes care of him in ways that make it almost seem that the boy is the parental figure and dad the needy dependent. But Ivo’s life isn’t otherwise placid. Though talented, he has a case of stage nerves and a reputation for unreliability that threaten his promising career.

Antonio’s other intimate, Lucia (Livia Rossi), is a young woman he meets while they’re both taking a standardized test (for what we’re never told). She looks completely at sea, so he passes her the answers, and a brittle friendship is born. But she’s hardly a cheerful or romantic companion. Beclouded by various worries, she seems on a downward psychological spiral that Antonio will be hard-pressed to reverse.

As this loose-knit tale unfolds, its most curious aspect is how disconnected its episodes feel, a quality that grows even more pronounced in its second half. It’s as if Amelio had a hatful of note cards with ideas for scenes, threw them in the air, and stuck them in the final script in whatever order they hit the floor. Some seem entirely arbitrary.

One example: Antonio is assigned by a shady gym boss to look after a boy who appears about 10 years old. He takes the kid to a park and tries to amuse him with jokes and chat, but the boy won’t talk. Eventually a man appears and the boy goes off with him. What’s happened here? Has Antonio played an unsuspecting role as a pedophile’s procurer? The scene vaguely evokes the concern for child abuse in other Amelio films, but here it’s never explained; it connects with nothing around it.

In the films that earned him an international reputation, Amelio seemed like an inheritor of the Italian neorealists, a powerful and confident stylist who nonetheless turned away from the aestheticism of directors such as Antonioni and Bertolucci to focus on social problems, often from an angle that might be called conservative-humanist. But “Intrepido” hardly seems like an attempt to seriously probe contemporary labor discontents; it’s too whimsical and aleatory. So what was Amelio’s plug-in point for this desultory fable?

It’s been reported that he wanted to work with Albanese, a popular comic actor, and “Intrepido” does make a certain amount of sense as a way for the director to showcase a favorite performer. The story’s random trajectory plays like a series of skits for the actor, more than a conventionally focused story. Also, there’s an obvious attempt to evoke the Chaplin of “Modern Times” (one sequence even ends with an iris-in). Yet it can’t be said that any of this adds up to slapstick merriment, much less clever satire. Amelio’s outlook is naturally grave; comedy is not in his genes; and if he’d wanted to work with an actor who could provide actual hilarity, he’d have been better off with an antic clown like Roberto Benigni.

What comes across as genuine in the film, and might also help explain its origins, is its air of melancholy and loneliness. The film’s Milan is not just a vision of wintry industrial anomie; it also feels like a place where people inhabit the same space but never touch each other. A space that’s more the inside of one man’s head than an actual city, in other words.

“Intrepido,” the title Amelio gave the film, refers to a publication from his childhood. “A Lonely Hero,” supplied by the film’s importers, is a rather clunky addition, but it does evoke the interior feel of the film. “Colpire al Cuore,” Amelio’s brilliant debut film of 1982, provided a scathing critique of bourgeois leftist radicals, yet it was also a depiction of a very solitary and alienated young man, and the suggestion of self-portraiture was inescapable. “Intrepido” may be a similar look in the mirror, yet here the face the artist sees is old, not young, and his world not so susceptible to cathartic change.