Thrillers are as good as their villains, and “In the Line of Fire” has a great one – a clever, slimy creep who insidiously burrows his way into the psyche of the hero, a veteran Secret Service agent named Horrigan (Clint Eastwood). The creep, who likes to play mind games with his opponents, makes a series of phone calls threatening to assassinate the president. He chooses Horrigan because he knows the agent still feels guilty about failing to save the life of John F. Kennedy 30 years ago.

The would-be killer has an all-American name, Mitch, and is played by John Malkovich as an intelligent, twisted man who uses disguises, fake ID and an ingratiating manner to get close to the president. He tells Horrigan more or less what he plans to do, and when, but Horrigan’s hands are tied. The president is running for re-election, and his chief of staff (Fred Dalton Thompson) doesn’t want him to look like a coward. So after Horrigan sounds a couple of false alarms, he’s taken off the White House detail, and has to break rules in order to stay on Mitch’s trail.

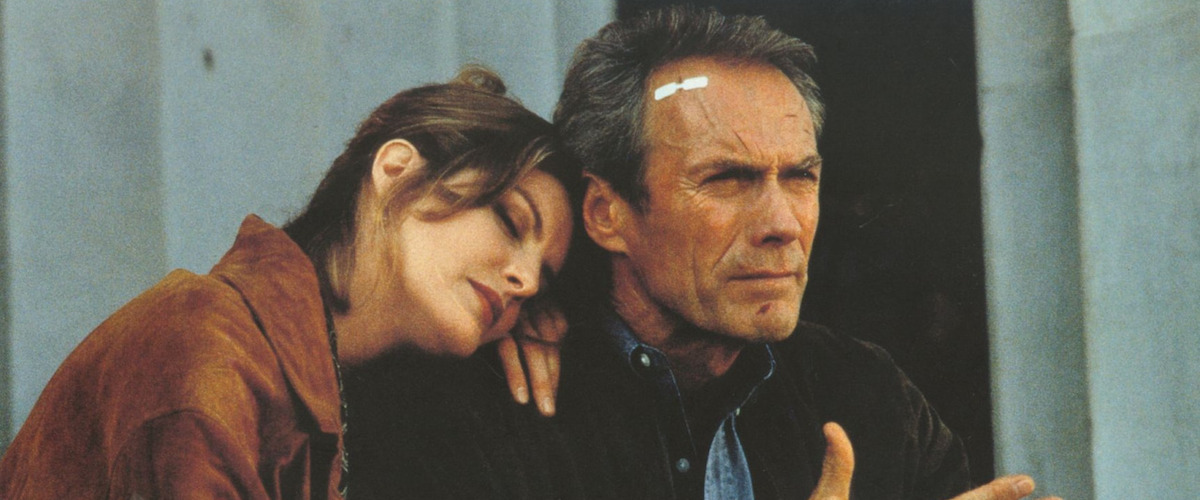

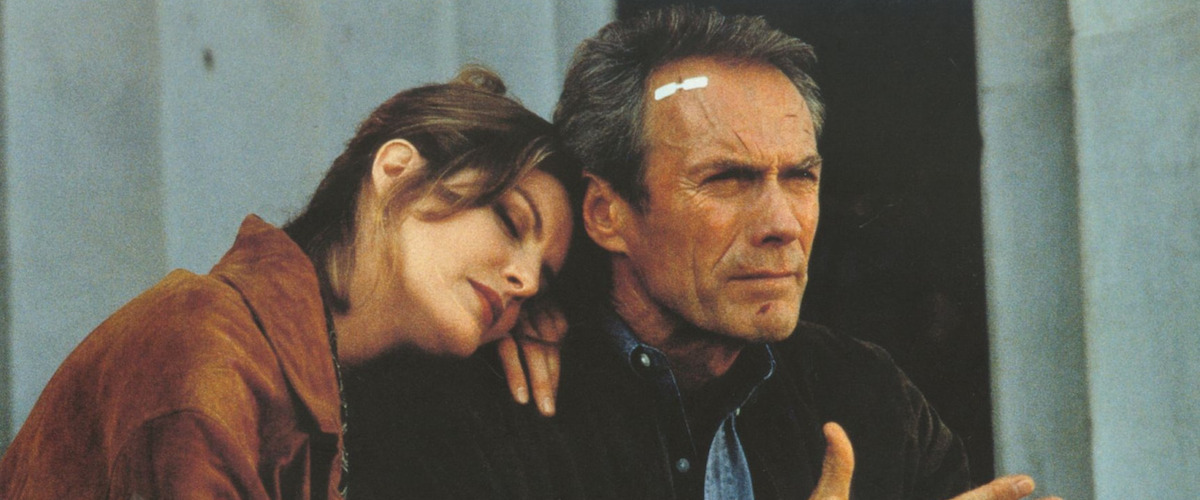

In its broad outlines, “In the Line of Fire” has a story similar to many of Eastwood’s “Dirty Harry” movies, in which a psycho killer plays games with the cop, who is ordered off the case and then continues as a free-lance, helped by a loyal partner. The movie even supplies a typical Eastwood sidekick, a woman agent played by Rene Russo, who is tough and capable, and able to fall in love.

Despite the familiar plot elements, however, “In the Line of Fire” is not a retread but a smart, tense, well-made thriller – Eastwood’s best in the genre since “Tightrope” (1984). The director is Wolfgang Petersen (“Das Boot“), who is able to unwind the plot like clockwork while at the same time establishing the characters as surprisingly sympathetic.

Horrigan, the Secret Service man, still blames himself for the Kennedy assassination. He feels he somehow could have made a difference. Mitch has done his research, knows all about Horrigan, and insidiously slithers into his mind with words aimed like poison darts. Soon the assassination attempt becomes a two-handed game, in which Horrigan is as much of an outsider as Mitch, and must protect the president almost against his will – and the will of his politically ambitious staff.

Russo, as Lilly, another agent, finds an interesting variation on the role of associate and lover. Her relationship with Horrigan begins on a rocky note, when he drops a couple of sexist statements, essentially accusing the Service of tokenism for hiring women. Well, OK, he’s an unreconstructed chauvinist pig, but eventually their respect for each other grows, and there is a wonderfully played moment when they concede they are attracted to one another.

Meanwhile, the plot advances relentlessly. After seeing “The Firm,” which was good but needlessly labyrinthine, it was a pleasure to follow the twists and turns of Jeff Maguire’s screenplay for “In the Line of Fire.” It doesn’t waste a line. Horrigan takes the clues that Mitch provides him, uses intuition and experience, breaks agency policy when necessary, and eventually finds himself testing the willingness that all Secret Serviceman are supposed to have – to take a bullet in place of the president.

Eastwood is perfect for the role, as a man of long experience and deep feelings. He is set off by an inspired performance by Malkovich, who is quiet and methodical and very clever, and devises a sneaky plan to work his way close to the president with an ingenious murder weapon. The movie’s climax is exciting not only because of its action, but also because of its flawless logic.

What’s surprising is how much time the movie finds for small touches of realistic detail and emotion. The conversations between Eastwood and Russo – about work, jazz, strategy and romance – sound as if they’re taking place between real people. The locations look convincing, especially Air Force One and some shots supposedly inside the White House. The special effects are good at inserting a young Eastwood into 1963 footage of Kennedy, establishing the character’s deep need to stop the new assassination he feels is coming. And the direction of the final scenes is as spectacular as it is skillful.

Yes, it’s unlikely that Mitch the killer would jump into that elevator (it’s an example, in fact, of the Fallacy of the Climbing Killer, in which villains always make the mistake of heading for a high place). But it allows an earlier situation to come around again as a sensational payoff. Most thrillers these days are about stunts and action. “In the Line of Fire” has a mind.