After the one-two gut punch of garbage filmmaking that was “Blacklight” and “Memory,” I had just about given up on Liam Neeson, an actor of undeniable quality who seemed to have stopped actually reading scripts all the way through before signing onto projects. Despite its flaws, one can’t say that about Robert Lorenz’s “In the Land of Saints and Sinners,” a film that could throw off Neeson’s VOD audience by virtue of being more of a drama than an action film but could also bring those who had given up on his late career back into the fold.

Actually, this one is more of an existential Western at its core, even though its set in Ireland during The Troubles. Lorenz has been a regular collaborator with Clint Eastwood for decades, producing films like “Mystic River,” “Million Dollar Baby,” and “American Sniper,” and it’s not hard to see Eastwood himself in a heartland-set version of this tale with little script alterations. It’s another story of a man who has done evil things but maintained a moral conscience through it all that is now being tested by someone who lacks such conviction. While it meanders more often than it should with some pretty slack pacing, strong character work by Neeson and an excellent supporting cast hold it together.

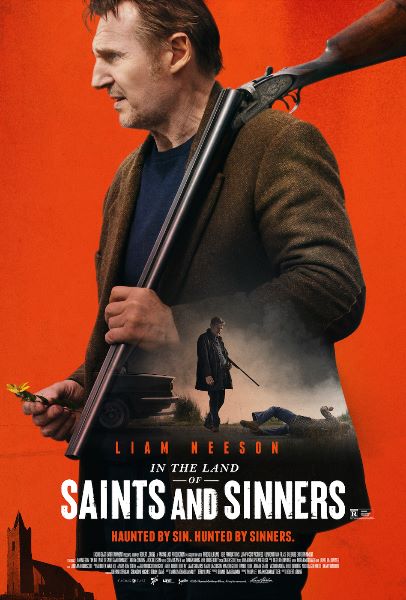

An Avengers-esque number of great Irish performers star in “In the Land of Saints and Sinners,” led by Neeson as an assassin with the great name of Finbar Murphy. He works for a local tough named Robert McQue (Colm Meaney), and he plants a tree on the ground dug out by his victims before he shoots them. Let’s just say there’s a forest of Murphy’s victims on the edge of this Donegal town. Of course, like any anti-hero in a Western like this one, Murphy is ready to put his shotgun away and live out his remaining days at the local pub, chatting with his buddy Vinnie O’Shea (Ciaran Hinds), the local Garda. Life will have other plans.

The film actually opens with a bombing orchestrated by an IRA terrorist named Doireann McCann (Kerry Condon, Oscar-nominated for “The Banshees of Inisherin”) that goes horribly wrong, leading to the death of three children. Avoiding the authorities, McCann and her cohorts go into hiding in Murphy’s village, eventually crossing paths with the good folk who live there. When Doireann’s brother does something horrifying, he ends up a target of Murphy, setting in motion a series of events that has to inevitably lead to bloodshed.

That inevitability is a blessing and a curse for “Saints and Sinners.” While there’s something charming about the simplicity of Mark Michael McNally & Terry Loane’s script, it goes a bit too far in the mid-section of the movie when the narrative starts to sag. We know where this is going, and Lorenz isn’t visually strong enough as a director to maintain tension within that predictability. There are times when this film sags notably, unsure if it’s supposed to be building stakes or just treading water.

Lorenz turns out to be a much better director of performers, although this all-star team was likely pretty easy to direct. The always-welcome Hinds is kind of under-used, but Condon is great in what is basically the villainous Man in Black role from the Western template. As opposed to some of his recent career lows, Neeson actually finds some subdued chords here, sketching a man who knows he’s done bad things but has made his own peace with God.

On that note, there are some underdeveloped ideas in “Saints and Sinners” regarding religion, sin, and redemption that could have helped during its narrative sag. The film’s Irish setting demands a bit of that, but it doesn’t feel like it’s been carefully considered like it would be in a more accomplished character study. Too much of “In the Land of Saints and Sinners” is content to skim the surface, only reaching underneath it because of a smart acting choice by its great cast. Luckily, the surface of Northern Ireland is just gorgeous enough to practically be a character itself, enhancing a film that embraces its familiarity. It might even resurrect your faith in Neeson’s future roles.