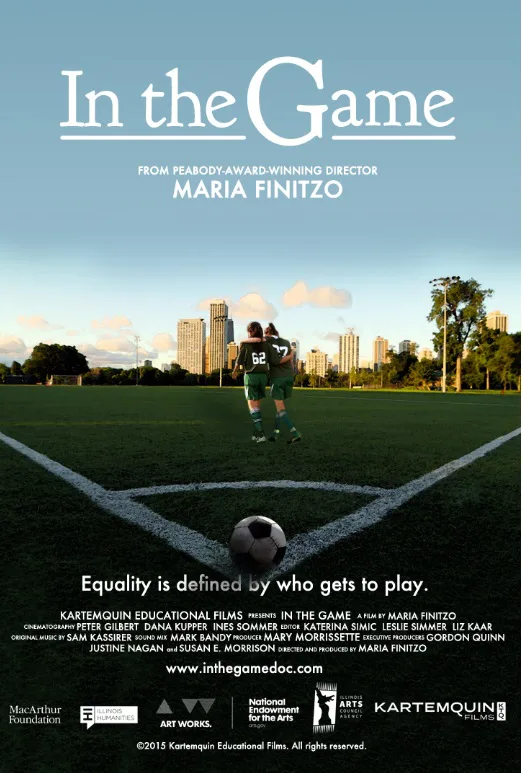

Stan Mietus is the kind of role model that we all hope our children someday encounter in their lives. When we send our kids off to school or to athletic programs, we place an incredible amount of trust in the people paid to teach and coach them. Mietus understands, as clichéd as it sounds, that he’s teaching young people that it’s really not whether you win or lose, but how you play the game and how you respond to adversity that defines your character. He’s teaching teamwork, confidence, and, yes, that life is unfair. You will lose in life, but it’s how you respond that matters more than the losing. Mietus is one of the central figures in Maria Finitzo’s “In the Game,” premiering at the Siskel Film Center tomorrow, August 22nd, with screenings throughout the next week (go here for more details). It’s a project from Kartemquin Films, the brilliant people behind Steve James’ “Life Itself,” and the best sports documentary of all time, “Hoop Dreams.” Much like that film, Finitzo uses sports—girls’ soccer this time—to comment on other issues, including income inequality and gender roles, but she does so with a light tough, always keeping the focus on the players on the field more than the entire game.

For four years, Finitzo and her crew went back to Kelly High School on Chicago’s Southwest side, catching up with Mietus and the players on his soccer team. The first of these young women we meet was up until 2am the night before studying and woke at 4:30am for soccer practice, which takes place in the hall sometimes because there’s not enough space in the gym and they don’t have a working field. It’s a school that’s 83% Latino and 86% below the poverty line. Over the course of “In the Game,” we will watch young women forced to make life’s difficult decisions, often between school and work to help support their families. These are decisions made every day in major cities around the world, and “In the Game” is a stark reminder of how quickly life can force teenagers to become adults, especially when they don’t have the luxury of making any other choice.

What’s most fascinating about “In the Game,” and it’s remarkable how much Finitzo allows this element to unfold naturally and without underlining, is that the young ladies that the film captures all have a striking resilience about them. Some will be faced with tragedy. Some will be faced with closed doors. Some will be faced with heartbreak. And yet they hold their heads up high and keep going in ways that I don’t believe everyone would. I think a lot of that credit can go back to Mietus and the fortitude one gains from team sports the way he teaches them. There are times in life when your opponent will have more privilege, such as when Kelly plays Whitney Young, one of the top soccer high schools in the country. They have no chance of winning. And yet they play. They get out there. They work as a team. The idea that we can persevere against a system that often stacks the deck against us is as important as any we can learn.

“In the Game” doesn’t position itself as a “statement film.” There are no statistics emblazoned on the screen. It is a study of one school athletic program and its players. And yet it feels more important than that. It feels empowering, even inspirational. You will lose some games. In life, you will play some games that you never had a chance of winning. But the important thing is that you keep playing.