There is an image in “Immortal Beloved” as evocative as any I can remember – as complete as the sled in “Citizen Kane,” or the shadowy doorway in “The Third Man.” A boy runs through the forest at night to a perfectly still lake, and floats on his back. The camera pulls back, and we see the stars of the sky reflected in the water.

And then it seems as if the boy is floating in the firmament – lost in the stars. On the soundtrack, we hear the “Ode to Joy” from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

Movies that attempt to match visual images to great music are often asking for trouble. Remember the “1812 Overture” playing in Ken Russell’s biopic of Tchaikovsky, the cannon roars illustrated by images of soldiers’ heads being blown off? What Bernard Rose has accomplished in “Immortal Beloved” is a film that imagines the mental states of Beethoven with a series of images as vivid and convincing as a dream.

The film unfolds like a biographical puzzle. Beethoven after his death left a letter addressed to his “immortal beloved,” with no hint as to who that person was. As a last testament this document may have been faulty, but as a biographical puzzle it was a masterstroke, inspiring two centuries of fevered speculations, of which this film is the latest and most romantic. I doubt Rose has solved the puzzle of the unnamed beloved, but I care not, because he has done something more valuable: He has created a fantasy about Beethoven that evokes the same disturbing, ecstatic passion we hear in his music.

The film opens with Schindler (Jeroen Krabbe), Beethoven’s confidante, beginning a search for the immortal beloved. As he visits first one and then another possible source of information, it is impossible not to be reminded of the hapless reporter who sought the meaning of “Rosebud” in “Citizen Kane.” As he visits the important women in Beethoven’s life, we see flashbacks to the composer’s disorderly and precarious existence, and we hear music, magnificent music.

Unusual for the director of a musical biography, Rose has paid as much attention to the music as to the biography. Most biopics about classical composers dredge up obscure, low-rent recordings of the music. Not this one. The film’s musical supervisor is Sir Georg Solti, conducting the London Orchestra, with soloists such as Murray Perahia and Yo-Yo Ma. If there are moments when we doubt Beethoven was thinking exactly these images as he composed, there are others when the momentum of the story takes over, and we identify with a tortured genius whose deafness cut him off from the immortal sounds he was giving to mankind.

Beethoven is played in the film by Gary Oldman, who at first seems an unlikely choice: Too small, too driven, too insinuating.

Then we see that he is right. He is a man on the edge of madness, obsessed with women, even more obsessed with Karl (Marco Hofschneider), the young nephew he hopes to turn into a prodigy. He wages a lifelong campaign of hate against Karl’s mother, Johanna (Johanna Ter Steege), telling his brother Caspar (Christopher Fulford) she is a foul slut. The movie proposes an interesting explanation of Beethoven’s hatred of her and love for her son, one which sensible biographers will question, but that fits perfectly with the terms of the story.

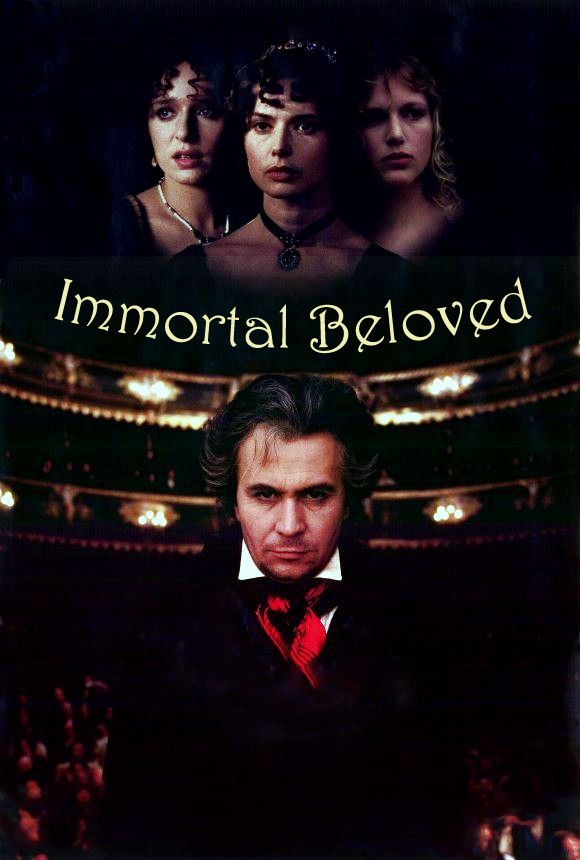

If Johanna is, by default, one of the three most important women in Beethoven’s life, the other two are Countess Giulietta Guicciardi (Valeria Golino), who becomes his student and patron, and the older, wiser Countess Anna Maria Erdody (Isabella Rossellini), who stands up to Beethoven after he has gone into court to wrest young Karl away from Johanna, his mother.

In the scenes with Giulietta we see Beethoven’s status as the most sought-after lion of the European musical scene; in his day, a great composer was the equivalent of today’s rock stars, swooned over and showered with attention. He becomes the countess’ piano teacher, but does not always play the game according to her world’s rules: “A mistake is nothing,” he tells her, “but the fact that you thump out the notes without the least sensitivity to their meaning is unforgivable, and your lack of passion is unforgivable. I shall have to beat you.” She thinks he is teasing until he slaps her so hard that tears well in her eyes.

The scenes with the Rossellini character are among the best in the film, because here he finds a haven from his debts, from his troubles with the law, from his wars with his relatives, from his fawning admirers and mocking rivals. She sees most clearly his curious obsession with young Karl, which takes an odd turn: Beethoven stops composing entirely for five years in order to supervise Karl’s education as a music virtuoso, despite the boy’s tearful pleas to be allowed to become a soldier.

Beethoven’s deafness is a subject through much of the film, including a precarious scene where the Rossellini character leads him from the stage after he grows confused during a public performance, and another in which he touches the wood of a pianoforte to hear the music through his fingers. He tried desperately to conceal his deafness, fearing it would destroy his livelihood, and on the soundtrack Rose sometimes reproduces what he can hear: Low rumbles curiously like the music of the whales.

This is the fourth film by the young British director Bernard Rose, after “Paperhouse” (1989), “Chicago Joe and the Showgirl” (1990) and “Candyman” (1992). The first was a masterpiece, a haunting fantasy about the secret mental worlds of children. The second, set in World War II, was a fanciful recreation of a relationship between a GI and a British girl, both living in their delusions. The third was about a legendary figure said to haunt Chicago public housing projects. In all three films Rose shows a remarkable gift for visualizing his themes: His films are stimulating to look at.

Here, in the shopworn genre of the musical biopic, he makes everything new. “Immortal Beloved” has clearly been made by people who feel Beethoven directly in their hearts, and are not approaching him through a classroom or historical setting. Beethoven writes to Schindler at one point, arguing: “It is the power of music to carry one directly into the mental state of the composer. The listener has no choice. It is like hypnotism.” The viewer of “Immortal Beloved” likewise has no choice, and for the same reason.