“Chicago Joe and the Showgirl” begins on two different notes at the same time. A theater curtain opens, suggesting that we are about to see a made-up story, while titles on the screen inform us that the film is based on real events. The film tries to maintain a balance between those two kinds of reality – between a series of crimes that eventually led to murder, and a fantasy-world in which movies images were more important than actual events.

The movie is set in London, in the later days of World War II, when the Yankee presence had made a profound impact on British culture.

Movies from Hollywood had been filling the cinemas for years, and now here were thousands of servicemen with their American accents, their loud voices and confident swagger, and their pockets full of cigarettes. Two people meet, one British, one American, both with a borderline connection to reality, and their chemistry leads by one foredoomed step after another to tragedy.

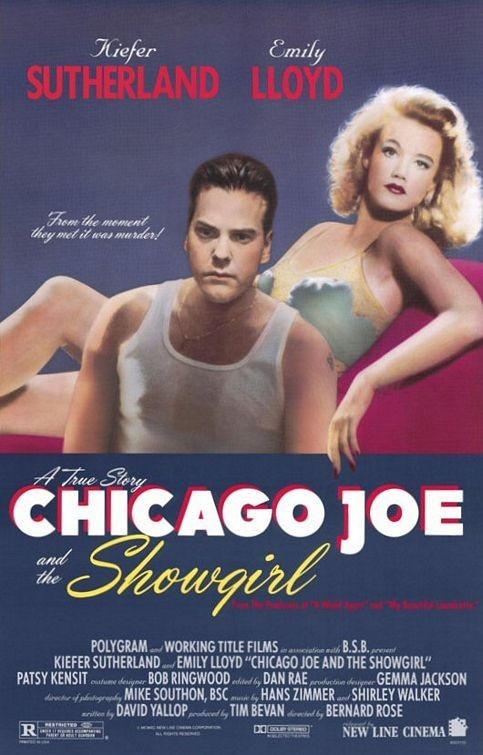

The British character, the “showgirl” (Emily Lloyd), begins to project her fantasies on the American almost from the moment she meets him. She wants him to be a movie character, somebody like a gangster from Chicago. The G.I. (Kiefer Sutherland) goes along. He’s leading a shadow existence of his own, after going AWOL from the Army with a stolen truck. Together they cruise the blacked-out streets of London, while wartime music plays and they begin to believe they’re characters in each other’s movies.

They begin to commit crimes. He steals a fur coat for her, for example, and they stick up a store. Their crimes are so reckless they get away with them almost through dumb chance. He drives up in the big Army truck, dashes out, steals something, and they roar away.

How can they possibly avoid being caught? In a way, director Bernard Rose stacks the deck by shooting his movie almost entirely on sound stages. Even the exteriors are sets. This creates a certain air of artificiality; the movie looks like a movie, which helps explain some of the scenes that could only happen in a movie. Another reason for their charmed lives is that their stunts are done with such sheer audacity that onlookers can scarcely believe their eyes.

It’s possible that neither one of these characters would have broken the law on their own – that their criminal impulses feed off each other, and off of their sudden romantic passion. Certainly the woman is aroused by the criminal aura surrounding this strange American, and I was reminded of a similar chemistry in “Bonnie and Clyde.” Another similarity is the way a crime spree starts out to be fun, and ends in the death of an unlucky bystander. But “Chicago Joe and the Showgirl” adds an element that wasn’t so obvious in “Bonnie and Clyde,” the shadowy suggestion that both of these characters have deep mental problems, big difficulties in dealing with reality.

All of this sounds intriguing, I suppose, and “Chicago Joe and the Showgirl” is a good-looking film that suggests the terrors that can be hidden in fantasy (Bernard Rose’s previous film, the brilliant “Paperhouse,” explored the same notion). But somehow “Chicago Joe” never quite catches fire, never quite overcomes the ideas in the screenplay to find an energy of its own. I didn’t feel as if the two characters were really acting out of their own spontaneous impulses; instead, they seemed to be guided by the writer and director. Their fates, like those of many fictional characters, seemed less tragic because they were preordained by the material.

Yet the performances themselves are convincing. Kiefer Sutherland has been one of the busiest young actors in Hollywood, and he’s versatile (in upcoming roles, he plays a student and a cowboy).

Because he’s prolific, there’s a tendency to take him for granted, but he’s good, all right, and here he does a scary job of creating a character who leads a double life (in addition to the “showgirl,” he has a conventional engagement under way with a middle-class girl who thinks he’s an upstanding young man). Emily Lloyd shows again, in only her fourth role, what a remarkable new talent she is. She’s so completely relaxed on the screen, so natural and seductive in the way she gets him to do whatever she wants.

Maybe if the movie had been just a little more realistic, less of an exercise in its own notions, the performances of the two actors would have created the kind of chemistry that happened in “Bonnie and Clyde.” But it doesn’t quite happen.