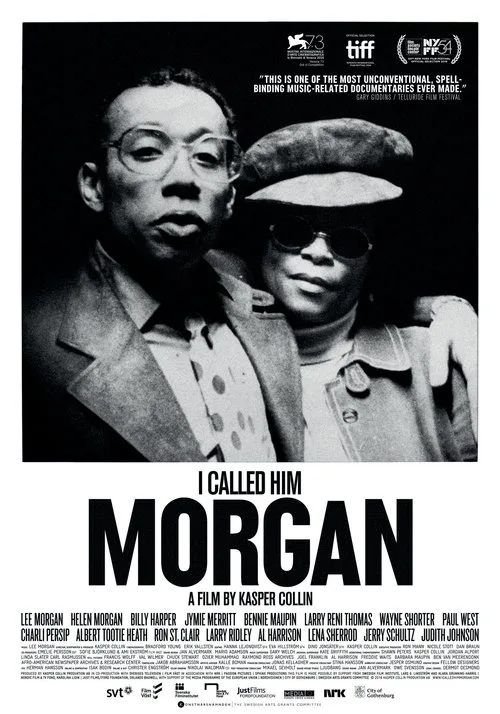

The jazz trumpeter Lee Morgan made exuberant music. Sufficiently exuberant and catchy that he achieved that rarity, getting a post-bop tune on the pop charts at the near-height of U.S. Beatlemania. The 1964 tune was called “The Sidewinder” and in a way the blessing of its popularity was a mild curse because it put Morgan in the awkward position of trying to follow it. Hence, LPs with titles such as “Tom Cat,” “The Rumproller” and “The Gigolo.” Not bad records—the tunes were catchy, and Morgan was such a spectacular trumpet player that he was always worth hearing—but not ones that necessarily “advanced” his music. By the late ‘60s he was once more exercising his musical voice with less self-consciousness about scoring a hit. (His 1970 “Live at the Lighthouse,” which pairs him with the ever-inventive reed player Bernie Maupin, is terrific.) But that voice would be silenced in 1972, in a tragedy of errors recounted in painful detail in this gripping, empathic documentary directed by Kasper Collin.

The linchpin of this movie is not Morgan himself; it’s not even Helen More, the woman who shot Morgan at the now-legendary jazz saloon Slugs on a snowy night in February 1972. Rather, it’s a cassette recording of an interview with More conducted by Larry Reni Thomas, an adult educator who met More in North Carolina, her home state, in the early 1990s, and helped More get a high school equivalency. “She wasn’t academically distinguished, but she was definitely street smart,” Thomas recalls. When More found out that Thomas was a jazz enthusiast, Lee Morgan’s name was mentioned. “I knew the story,” Thomas says. More told him that she was the surviving component of the story, and offered to tell her side to Thomas. The cassette, full of feedback, revealing More’s voice as slurry, sharp, tinged with regret, sometimes fond, and more, serves as the only narration in the movie. The rest is taken up with interviews and archival footage.

The most affecting interviewees are jazz greats Wayne Shorter and Albert “Tootie” Heath. Saxophonist Shorter came up with Morgan in Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, and Wayne speaks of Lee with a warmth and immediacy that one associates with a best friend. Near the end of the movie, Shorter, now 83, talks of how often he thinks of Morgan, and how often he says to people even now, “You should have known Lee Morgan.” In the archival clips and the generous snippets of music in the film, you are given some idea why: Morgan played with a remarkably clean tone (like so many of his peers, he was deeply influenced by the virtuosic Clifford Brown, whose death in 1956 at age 25 in an auto accident robbed jazz of a true great) and quicksilver energy. His playing had heat and humor. He had taken to bandstands before he was even 18. And like too many of his peers, he succumbed to substances and sensations of all sorts—Albert Heath recalls speeding in cars through Central Park’s roads in the wee small hours of a New York morning—and got a bad heroin habit. “What are you doing, Lee?” Shorter recalls thinking, while looking at a picture of Morgan from 1960 in which the trumpeter has a huge bandage wrapped around his head. Lee had shot up and dozed off—resting his head on a working radiator. The burn was such that he combed his hair forward the rest of his life to cover it up. Morgan’s addiction made him so unreliable that Blakey fired him from the Messengers along with pianist Bobby Timmons. (Timmons, whose soul-jazz tunes such as “Moanin’” achieved mainstream success not unlike that of “The Sidewinder,” died two years after Morgan, of cirrhosis.)

It was Helen More, several years Morgan’s senior, who discovered him at his most down and out, picked him up, formed a partnership with him, and helped him get healthy and productive again. “I called him Morgan,” she says on the tape, because she didn’t like the name “Lee.” More puts across a strong personality. A woman in an often very pig-headed man’s world, she brooked no disrespect. “Nasty, nasty,” she says of Miles Davis, recalling their one and only meeting, at which they both resolved to have absolutely nothing to do with each other after an exchange of maybe a couple of minutes. At some point, Morgan—who, one interviewee says, had been so physically damaged by drug use that he couldn’t have lived up to the title of “The Gigolo” even had he wanted to—grew emotionally attached to a different woman. Which did not sit well with Helen, who went one night in February to Slug’s with a gun in her purse.

Morgan might have survived his wounds on a different night. But on this one there was heavy snow, and the ambulance took an hour to arrive. And so he died, and More went to jail on a manslaughter charge. So many of Morgan’s pals had been den-mothered by More in the years before that their sorrow and rancor eventually gave way to forgiveness.

This movie is poignant; the personalities on display here are all beautiful, brave people. As much music as the movie showcases, this isn’t an analytical documentary. There’s no material about Morgan’s ability to fit in to both a somewhat commercial iteration of jazz and free modes of playing. And it sidesteps the “Sidewinder” years almost entirely. Its treatment of the music is more phenomenological. When Shorter explains using alcohol in the early days of his live playing to create a space for himself within both the music and the physical venue where he’d play, it’s a remarkable insight into the working life of a jazz musician at the time. “I Called Him Morgan” evokes times and places, and the sorrows and joys of the jazz life in those times and places, with real integrity.