Taika Waititi’s “Hunt for the Wilderpeople” shouldn’t work. It’s the kind of project that’s difficult to describe without making it sound clichéd and sentimental. It’s another coming-of-age tale, this one of a troubled teenager finding his place in the world deep in the mountains, with a man who never thought he’d be a father figure. And yet Waititi’s film defies its convention through grounded characters, witty dialogue, compassionate filmmaking and inventive storytelling. “Hunt for the Wilderpeople” is consistently clever and even moving. It’s proof that we’ll keep listening to the familiar stories if they’re this well-told.

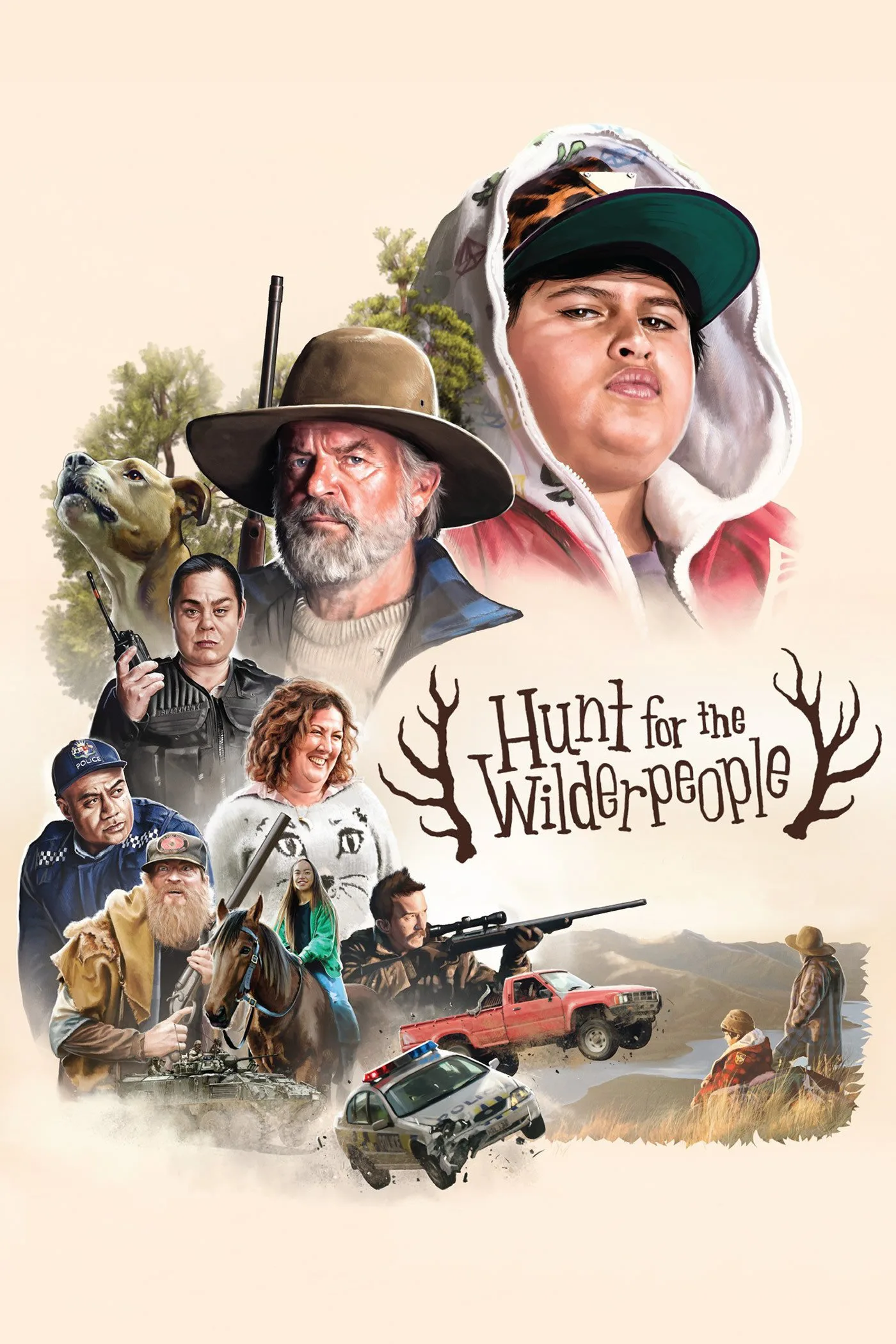

Teenager Ricky (Julian Dennison) is introduced as “a real bad egg.” He’s been shuttled around foster homes, getting in trouble for random juvenile things like loitering and graffiti. His officer, Paula (Rachel House) takes “No Child Left Behind” as a threat, not a comfort, focusing on Ricky like a problem that needs to be solved. She’s the kind of authority figure who sets Ricky up for failure, listing his problems instead of his qualities. And she’s immediately tonally offset by Ricky’s new mother, Bella (Rima Te Wiata), the kind of woman who wears sweaters with cat faces on them and hugs with her whole body. But Bella is no softie. She wins Ricky over by being honest, saying things like “Have some breakfast … then you can run away.” There’s a telling but brief exchange (Waititi never hammers or underlines his themes) in which Bella and Ricky see some wild horses and the young man asks if he can ride them. She responds, “Why do they need to be ridden anyway? Why can’t they just eat grass and be happy?” She’s essentially telling Ricky she’ll give him the same freedom.

Of course, nothing that great lasts and Ricky ends up on the run for reasons I won’t spoil. Deep in the forest, Ricky plans a life living off the land with his dog Tupac. He’s tracked and found by Bella’s husband Hec (Sam Neill), who gets injured, delaying their return to civilization long enough that the authorities come looking. Hec and Ricky are a traditional oil-and-water movie duo, physically and emotionally off-set. Ricky writes haikus. Hec hunts. And the two become famous, all over national news and tracked by the incompetent Paula. “Hunt for the Wilderpeople” becomes a road movie with no road, a film about two people who may seem entirely different but have both been discarded by society.

Waititi’s film never judges its characters. Ricky isn’t a “bad egg” or a “dumb kid.” The film finds joy in scenes like the one in which he creates a fake Walkman and dances to the music in his head. It’s essential to the film’s success that Ricky’s not just the bumbling idiot he could have been in another filmmaker’s hands. We feel honest affection for Ricky. And the same holds true for Hec, whom Waititi and Neill could have turned into a grizzled jerk. Dennison, Waititi and Neill find depth within the characters, as small moments become the foundation for the film’s emotion. They don’t play the coming-of-age arc, they play the reality of each scene. It may sound obvious, but so many films like “Hunt for the Wilderpeople” try to play the emotion instead of grounding it in character.

It helps to have a compassionate and humane filmmaker in the director’s chair. The man behind “Boy” and “What We Do in the Shadows” not only knows how hit a comedy beat with perfect timing, but he knows the rhythm a piece like this needs to work. With a fantastic editing team (there’s a sequence set to Nina Simone’s “Sinnerman,” of all things, that is perfectly conceived and executed), he breaks “Hunt for the Wilderpeople” up into chapters, making it feel almost like a memory or the story that an adult Ricky is telling his kids later in life. It almost approaches fairy tale mythology, especially the surprisingly action-packed finale, one in which we honestly care about the fate of our two protagonists.

So much of “Hunt for the Wilderpeople” looks easy. It’s not until one considers the number of places it could have gone awry that one truly appreciates it. There are so many minor beats that produce laughs and major moments that create surprising emotion. There’s a great scene halfway through in which Hec and Ricky are high enough in the mountains that they can almost touch the sky and Hec calls it “majestical.” It’s not a real word, but we know what it means. It’s the meaning that matters in “Hunt for the Wilderpeople.” It’s a downright majestical movie.