It was a desperate business, and “Hunger” is a desperate film. It concerns the fierce battle between the Irish Republican Army and the British state, which in 1981 led to a hunger strike in which 10 IRA prisoners died. The first of them was Bobby Sands, whose agonizing death is seen with an implacable level gaze in the closing act of the film.

If you do not hold a position on the Irish Republican cause, you will not find one here. “Hunger” is not about the rights and wrongs of the British in Northern Ireland, but about inhumane prison conditions, the steeled determination of IRA members like Bobby Sands, and a rock and a hard place. There is hardly a sentence in the film about Irish history or politics, and only two extended dialogue passages: one a long debate between Sands and a priest about the utility or futility of a hunger strike, the other a doctor’s detailed description to Sands’ parents about the effect of starvation on the human body.

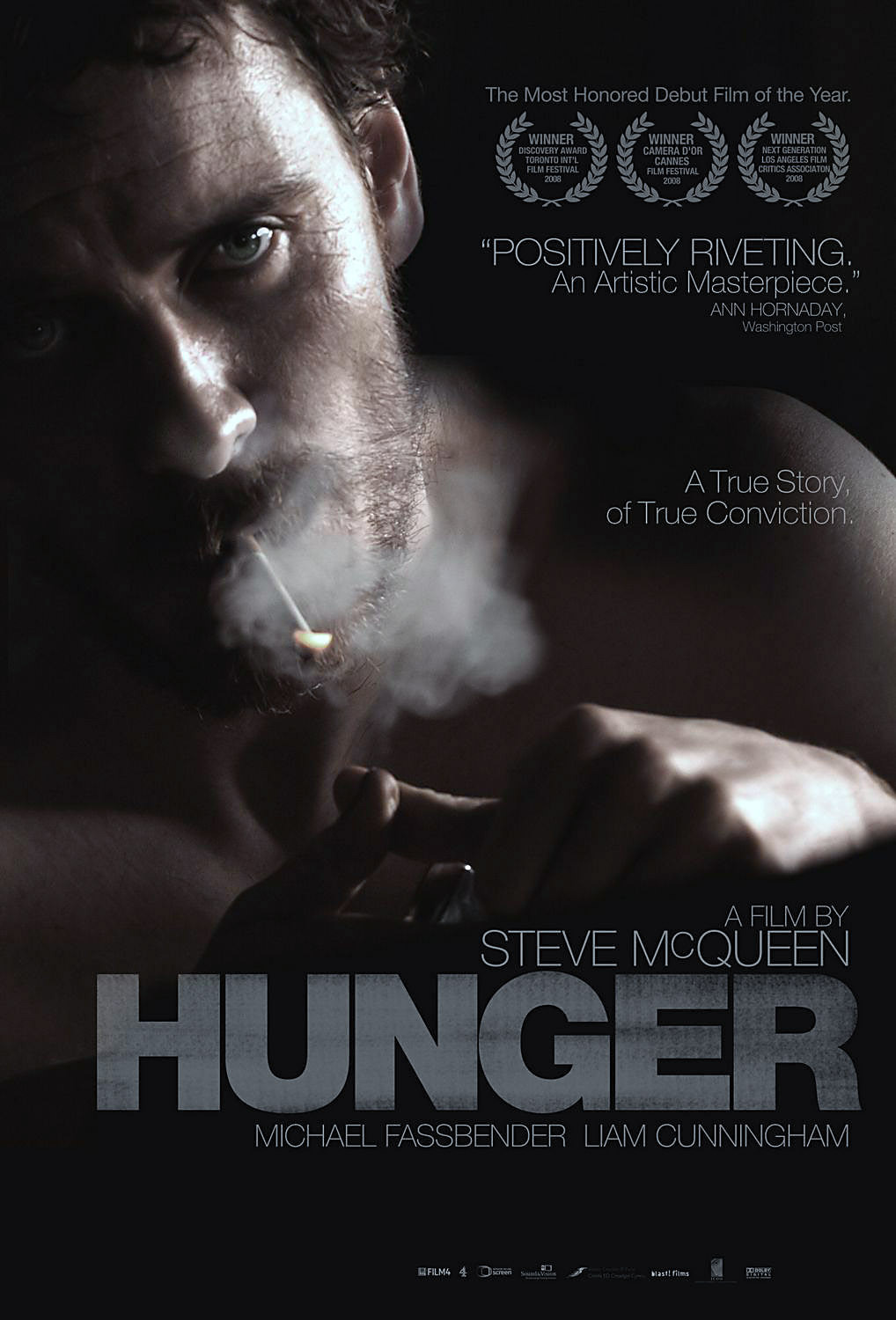

There is not a conventional plot to draw us from beginning to end. Instead, director Steve McQueen, an artist who employs merciless realism, strikes three major chords. The first involves the daily routine of a prison guard (Stuart Graham), who is emotionally wounded by his work. The second involves two other prisoners (Brian Milligan and Liam McMahon) who participate in the IRA prisoners’ refusal to wear prison clothes or bathe. The third involves the hunger strike.

This is clear: Neither side will back down. Twice we hear Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher describing the inmates of the Maze prison in Belfast not as political prisoners but criminals. The IRA considers itself political to the core. The ideology involved is not even mentioned in the extraordinary long dialogue scene, mostly in one shot, between Sands and a priest (Liam Cunningham) about whether a hunger strike will have the desired effect. The priest, worldly, a realist, on very civil terms with Sands, never once mentions suicide as a sin; he discusses it entirely in terms of its usefulness.

Sands thinks starvation to death will have an impact. The priest observes that if it does, Sands will by then be dead. His willingness to die reflects the bone-deep beliefs of Irish Republicans; recall the Irish song lyric, “And always remember, the longer we live, the sooner we bloody well die.”

Sands’ death is shown in a tableaux of increasing bleakness. It is agonizing, yet filmed with a curious painterly purity. It is alarming to note how much weight the actor Michael Fassbender lost; he went from 170 to 132 pounds. His dreams or visions or memories toward the end, based on a story he told the priest, would have been more effective if handled much more briefly.

Did the hunger strike succeed? After the remorseless death toll climbed to 10, Thatcher at last relented, tacitly granting the prisoners political recognition, although she refused to say so out loud. She was called the Iron Lady for a reason. Today there is peace in Northern Ireland. The island nation is still divided. Bobby Sands is dead. The priest has his conclusions, the dead man has his, or would if he were alive.