I’ve been waiting for eight years – since September 1968, to be exact – to review “Hugo and Josefin.” It was one of the genuine hits of that year’s New York Film Festival, a gentle, charming and scary children’s film that was for adults, too. It came from a young Swedish filmmaker named Kjell Grede, who was somehow able to project himself back into a children’s world in which grown-ups, empty barns and saying goodbye are hard to understand. The film was purchased for the American market by Warner Brothers, which still holds the rights. But the studio changed hands soon afterwards, and the film was never released commercially. At a time when every summer Saturday brings a rip-off kiddie matinee, this is a film to treasure.

It’s not an easy film, although I suspect kids will find it easier than their parents. Adults are always looking for meanings and connections; kids know nothing makes sense and that the most amazing surprises are around the next corner. What Grede does so magically is to create two worlds within the same film. After the New York screening, adults were trying to apply a realistic structure to the film, but the children in the audience matter-of-factly accepted it as a series of events in the life of the heroes.

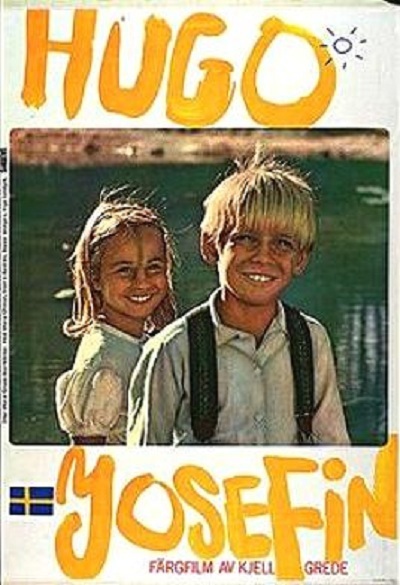

The heroes are two, Josefin and Hugo, a shy but beautiful little girl and the self-reliant little boy who comes to live near her. He knows things about walking through the woods and riding old-fashioned bicycles and whittling sticks. She knows things about getting along with people and wrapping adults around her little finger. They have a lot to learn from each other.

The children make a friend of Gudmarsson, the gruff, bewhiskered gardener who lives nearby. He’s the kind of adult who understands children enough to treat them with level solemnity and a wink in his eye. And every once in a while he’s around when they need to be rescued from adventures that suddenly turn menacing (Grede places Hugo and Josefin in a grown-up world of bulldozers and spooky warehouses, junkyards and hunters in the woods – they’re counterpoint to the Swedish pastoral look of most of the film.)

There are also scenes treated as pure fantasy, and yet Hugo and Josefin accept them as rationally as the others. That’s because they don’t know what’s not possible. Hugo races downhill on his outsize bicycle, and Josefin makes a sunflower peep in at a window, and then there’s the film’s beautiful final scene. The gardener packs his belongings and leaves in a pickup truck. The two children race after him. He stops, unloads a table, chairs, a couch and a grandfather clock from the truck and sets up housekeeping in the middle of the road.

Dinner is served: hard-boiled eggs. He puts a whole one in his mouth. So does Hugo. Then Josefin does, and the way she breaks into giggles with a whole hard-boiled egg in her mouth is worth perhaps six dozen hours of the summer’s Hollywood releases. Then dusk falls, and the gardener lights an oil lamp. There they all are in the middle of the empty country road, and there we are, confronted with the way a movie can win our hearts.