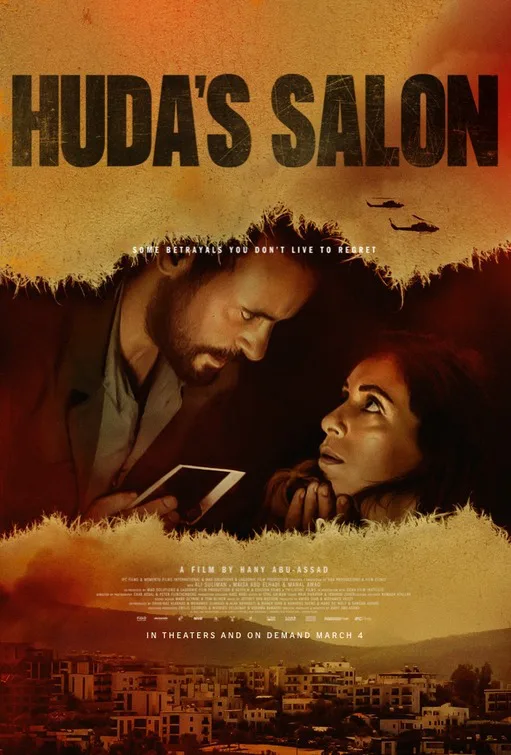

The first scene in Hany Abu-Assad‘s “Huda’s Salon” unfolds in an unbroken ten-minute take, showing hairdresser Huda (Manal Awad) tending to her lone customer, a woman named Reem (Maisa Abd Elhadi). The women gossip about their lives, about social media, Reem talks about her new husband’s jealousy. The salon may be a makeshift storefront in the occupied city of Bethlehem, under the shadow of the Separation Wall, but the conversation is your regular everyday hair salon chit-chat. At the end of ten-minute take, something happens, something that sets in motion every horror to follow over the film’s nerve-racking 90-minute runtime. Some reviews “spoil” what happens in this moment, but I went in cold, an experience I highly recommend. The moment is so unexpected, so shocking, particularly after the casual energy of the preceding conversation, I never recovered my equilibrium. Abu-Assad has carefully constructed the opening scene to bring his audience where he wants them to be. Once he has us, he does not let go.

It is enough to say that Huda is working secretly with the Israeli Occupation forces, informing on her own community, giving up the locations of wanted individuals, weapons caches, etc. She uses her salon as a cover as well as a recruitment center, where she skillfully blackmails her salon clients into service before they even know what is happening. Being branded as a “traitor” is the worst possible thing that can happen in such a besieged and tight-knit community. Even a rumor of collaboration can bring someone down. Even worse, the families of those suspected are also punished, denied permits, killed even. If you are “compromised,” then you compromise everyone around you, via guilt by association. This is the situation in which Reem finds herself. From this point forward, she has no rest. Her life becomes a nightmare of tension and terror.

“Huda’s Salon” splits off into two separate narratives, one following Huda and one following Reem. Reem, traumatized, clutching her baby, returns home to her husband Yousef (Jalal Masarwa). She tries to pretend nothing has changed, but Yousef, alert to her tiniest mood-change (all of which he takes personally), keeps asking her what is wrong. She cannot share. She knows he will not have her back. She’s done nothing wrong, but she is in grave danger nonetheless. Huda, meanwhile, is abducted by the Palestinian secret police, and interrogated about the hapless women she’s roped into service. The secret police want the womens’ names. Huda, a formidable woman, refuses to give up the names. She knows what these men will do to the women, if found.

Flipping back and forth between the narratives, Abu-Assad, who also wrote the script, keeps tight control of the story. Nothing interrupts or slows down the breakneck catapult forward. There are really only four characters in the film: Huda, Reem, Yousef, and Hasan (Ali Suliman), the intimidating Palestinian operative in charge of questioning Huda (if Huda is formidable, Hasan is even more so). Reem knows that Huda being abducted is bad news, because of the blackmail material Huda has in her possession. Even worse is the general chatter in the community, all of which suggests Huda—and others like her—should be shown no mercy. Reem hasn’t even “made contact” with the Israeli side yet. She hasn’t done anything wrong.

The interrogation scene between Huda and Hasan lasts for the entirety of the film, and it’s masterfully done (both written and performed). It’s a stand-off between two equal opponents, matched in intelligence, cunning, and courage. Hasan has all the power, but Huda has the intel he needs. He tries different tactics. Huda has a story, because of course she does, everyone does. She didn’t start collaborating with the Occupation out of the blue. Suliman and Awad create the eddies and flows of this long interrogation scene. Hasan plays good cop and bad cop, although he warns her that there’s an even worse cop waiting just outside. The situation is terrible, but it is so much fun to watch these two actors work.

In Abu-Assad’s films “Paradise Now” (the first Palestinian film nominated for a Best Foreign Language Oscar) and “Omar,” he explores what happens when a society exists in a state of high-alert paranoia, its members all too willing to turn on one another. “Huda’s Salon” makes the radical assertion that Palestinian women are under not one but two levels of “occupation.” Being subjugated by the men in their lives, husbands, brothers, fathers, leaves them trapped, and vulnerable to recruitment. Why should women show loyalty to these Palestinian men, when the men show no loyalty towards them? Huda is up front with Hasan about this. He admits, “I know that our society needs a good wake-up call.” It’s one hell of a concession.

The abstract concepts discussed by Hasan and Huda play out in Reem’s storyline. The script is very well-constructed. Awad’s transformation—from smiling if beleaguered new mother, to a hyperventilating women who has lost everything, is excruciating. The short timeline—the whole film takes place in less than a week—turns up the flame. Nothing will ever be the same again for these four characters. “Huda’s Salon” asks the question: Who is the real enemy in this scenario? The scary guys skulking around Reem’s house, waiting to abduct and kill her, are her own people. Hasan asks Huda at one point, “Who should they fear more? Us or the Secret Service?” That is the question, one that Huda forces him to acknowledge.

“Huda’s Salon” does not stop for one second to take a breath, and the subjects revealed have enormous and urgent philosophical reverb.

Now playing in theaters and available on digital platforms.