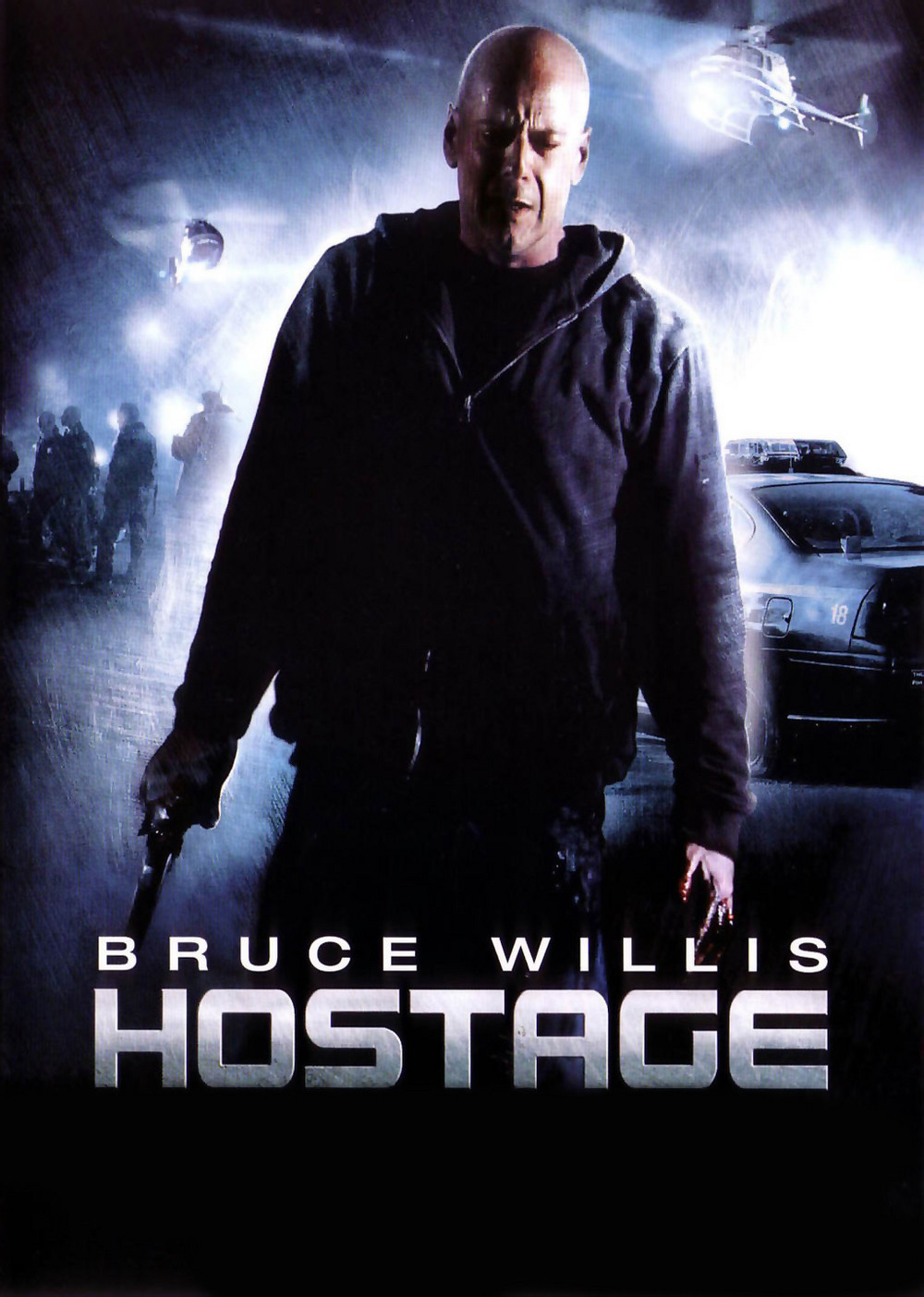

The opening titles of “Hostage” are shot in saturated blacks and reds with a raw graphic feel, and the movie’s color photography tilts toward dark high-contrast. That matches the mood, which is hard-boiled and gloomy. Bruce Willis, who feels like a resident of action thrillers, not a visitor, dials down here into a man of fierce focus and private motives; for the second half of the movie, no one except for (some of) the bad guys knows what really motivates him.

There’s also an interesting use of the movie’s three original villains, who are joined later by evildoers from an entirely different sphere. As the film opens, three gormless teenagers in a pickup truck follow a rich girl being driven “in her daddy’s Escalade” to a mountaintop mansion with fearsome security safeguards. Their motive: Steal the Cadillac. These characters are Mars (Ben Foster), a mean customer with a record, and two brothers: Dennis and Kevin Kelly (Jonathan Tucker and Marshall Allman). Kevin is the kid brother along for the ride, appalled by the lawbreaking Mars leads his brother into.

Trapped inside the house when police respond to an alarm, they take hostages: Smith, the rich man (Kevin Pollak), his teenage daughter Jennifer (Michelle Horn) and his young son Tommy (Jimmy Bennett). Willis plays the police chief who leads the first response team, but after a bad hostage experience in Los Angeles, he has retired to Ventura County to avoid just such adventures, and hands over authority to the sheriff’s department. Then, inexplicably, he returns and demands to take command again.

Moderate spoiler warning: What motivates him is that unknown kidnappers have captured Willis’ own wife and child, and are holding them hostage. They want Willis to obtain a DVD in the Smith house, which (we gather) contains crucial information about illegal financial dealings. So we have a hostage crisis within a hostage crisis, and Willis is trying to free two sets of hostages, only one known to his fellow lawmen.

This is ingenious, and adds an intriguing complexity to what could have been a one-level story. Some other adornments, however, seem unlikely. Little Tommy is able to grab his sister’s cell phone and move secretly throughout the house, using his secret knowledge of air ducts and obscure construction details. This development takes full advantage of the Air Duct Rule, which teaches us that all air ducts are large enough to crawl through, and lead directly to vantage points above crucial events in the action. Left unanswered is why the three hostage-takers aren’t concerned that the kid is missing for long periods of time.

Some elements exist entirely for the convenience of the plot. For example, the Kevin Pollack character functions long enough to establish his role and importance, then is conveniently unconscious when not needed, then is on the brink of death when Willis desperately wants to revive him, then miraculously recovers and is able to act with admirable timing at a crucial moment. I would love to examine his medical charts during these transitions.

But I am not much concerned about such logical flaws, because the main line of the movie is emotional, driven by the Willis character, who is able to project more intensity with less overacting than most of his rivals. He brings credibility to movies that can use some, and that will be invaluable in his forthcoming “Live Free or Die Hard.” The mechanics of the final showdown are unexpected and yet show an undeniable logic, and are sold by the acting skills of Willis and Pollak.

The movie was directed by Florent Emilio Siri, creator of two Tom Clancy-written video games, which may explain why some of my colleagues were chortling when the Willis character uses his knowledge of Captain Woobah and Planet Xenon (persons and places unknown to me) to reassure Little Tommy. I say, if you know it, flaunt it. If he had been quoting Nietzsche, now that would have been a red flag.

What Siri brings to the show is an intimate visual style that keeps us claustrophobically close to the action, an ability to make action sequences clear enough to follow and a dark sensibility that leads to at least two deaths we do not really expect. In scenes where a hero must outgun four or five armed opponents, however, “Hostage” does use the reliable action movie technique of cutting from one target to the next, so that we never see what the others are doing while the first ones are being shot. Waiting for their closeups, I suppose.