To explain the special strength of “High Art,” it is necessary to begin with the people who live in the apartment above Syd and James. There’s a shifting population in the upstairs flat, since drugs are involved, but the permanent inhabitants are Lucy, who was a famous photographer 10 years ago; Greta, who once starred in Fassbinder films; and Arnie, an unfocused layabout who’s along for the ride, and the heroin.

Syd has just been made an associate editor of a New York photo magazine–the kind with big pages, where you have to read the small print to tell the features from the ads. She goes upstairs because there’s a leak coming through the ceiling, and walks into the sad, closed, claustrophobic life of the heroin users. And now here is my point: Those people really seem to be living there. They suggest a past, a present, a history, a pattern, that has been going on for years. Their apartment, and how they live in it, is as convincing as a documentary could make it.

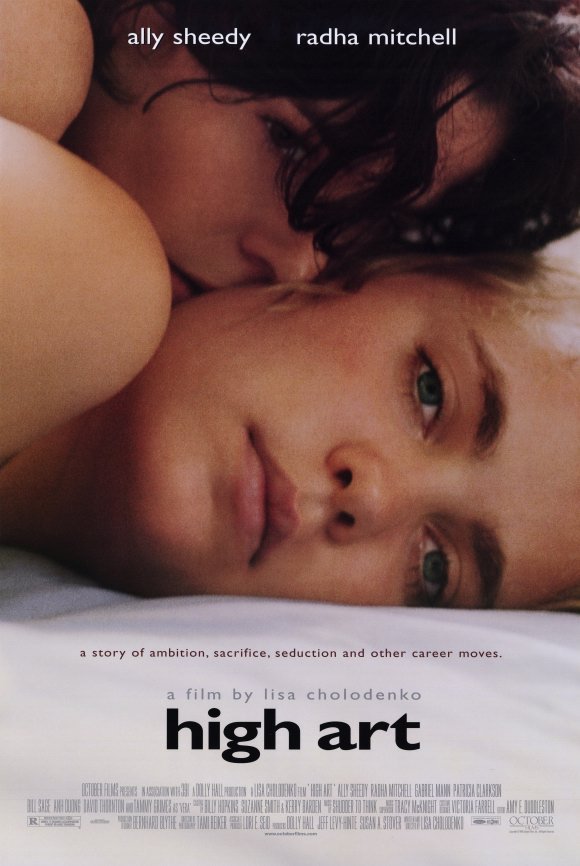

In other words, they aren’t “characters.” They don’t feel like actors waiting for the camera to roll. And by giving them texture and complexity, writer-director Lisa Cholodenko has the key to her whole movie. The couple downstairs, Syd (Radha Mitchell) and her boyfriend James (Gabriel Mann), are conventional movie characters–Manhattan yuppies. It’s not that they seem false; it’s that their lives are borrowed from media. Then Syd senses something upstairs that stirs her.

To begin with, she sees some photographs taken by Lucy (Ally Sheedy). They’re good. She tells her so. “I haven’t been deconstructed in a long time,” Lucy says. Lucy is thin, a chain-smoker, projecting a kind of masochistic devotion to the older Greta (Patricia Clarkson). Both are deeply into drugs. Greta seems to drift between lassitude and oblivion; she’s like a Fassbinder movie so drained of life it doesn’t move anymore. She falls asleep during sex with Lucy. She nods off in a restaurant, and the waiter tells Lucy: “You know this restaurant has a policy about sleeping in here.” Syd is on the make. She wants to move up at her magazine. Her editor, the often hung over Dominique (Anh Duong), started as a receptionist at Interview–so all things are possible. Syd pitches Lucy’s photos to Dominique. “She was so belligerent when she left New York,” Dominique muses. They set up a luncheon. “I made it impossible for myself to continue,” Lucy explains about her dead career. “I stopped showing up.” Dominique asks Lucy to do a shoot for the magazine. Lucy insists on Syd being her editor. Gradually, by almost imperceptible degrees, the two women are drawn toward one another. Greta sees what is happening. But her hold on Lucy is strong: a triangulation of drugs, exploited guilt and domination. She knows what buttons to push.

“High Art” is masterful in the little details. It knows how these people might talk, how they might respond. It knows that Lucy, Greta and the almost otherworldly Arnie might use heroin and then play Scrabble. It is so boring, being high in an empty life. The movie knows how career ambition and office politics can work together to motivate Syd: She wants Lucy to get the job because she’s falling for Lucy, but also because she knows Lucy is her ticket to a promotion at the magazine.

Finally, at what seems like the emotionally inevitable moment, Syd and Lucy sleep together. This is one of the most observant sex scenes I have seen, involving a lot of worried, insecure dialogue; Syd feels awkward and inadequate, and wants reassurance. Lucy provides it from long experience, mixed with a sudden rediscovery of the new. They talk a lot. Lucy is like ground control, talking a new pilot through her first landing.

The movie is wise about drug addition. There are well-written scenes between Lucy and her mother (Tammy Grimes), who keeps her distance from her daughter. Lucy looks at her life and decides, “I can’t do this anymore.” She tries to open up with her mother: “I have a love issue and a drug problem.” Her mother closes her off: “I can’t help you with that.” Lucy is tired of Greta, tired of drugs, tired of not working, tired of boredom. Greta’s final, best weapon, is heroin: Can she keep Lucy with that? Or will Lucy be able to see that Greta is only the human face of her addiction? “High Art” is so perceptive and mature it makes similar films seem flippant. The performances are on just the right note, scene after scene, for what needs to be done. The reviews keep mentioning that Ally Sheedy has outgrown her Brat Pack days. Well of course she has. (She’d done that by the time of “Heart of Dixie,” in 1989.) Patricia Clarkson succeeds in creating a complete, complex character without ever overplaying the stoned behavior (she’s like Fassbinder’s Petra von Kant on heroin instead of booze). Radha Mitchell is successful at suggesting the interaction of several motives: love, lust, curiosity, ambition, admiration. And the ending does not cheat. Just the opposite.