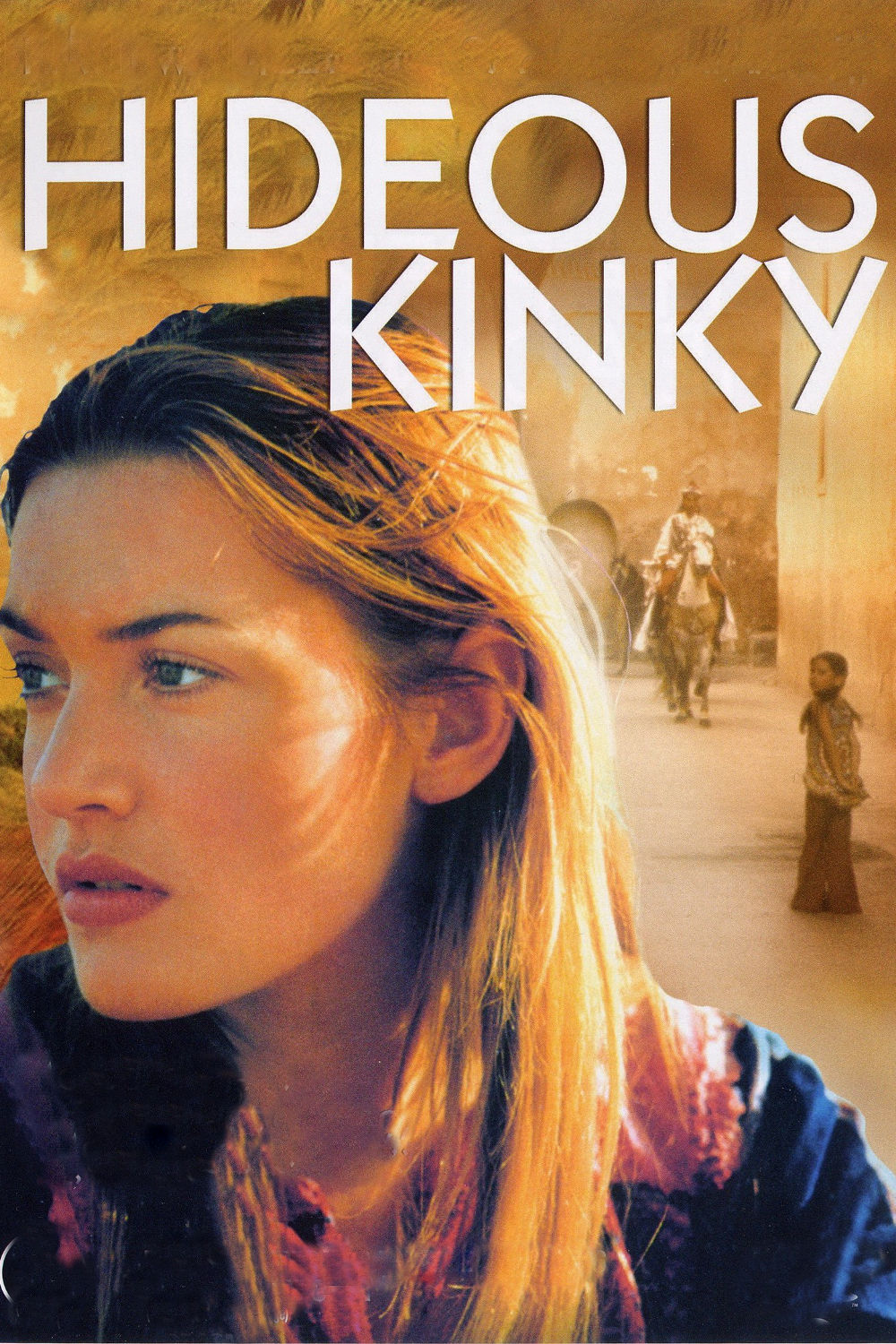

In the 1970s, there were movies about the carefree lives of hippies and flower people, and on the screen you could see their children, long-haired, sunburned and barefoot, solemn witnesses at rock concerts and magical mystery tours. Remember the commune in “Easy Rider.” Now it is the 1990s and those children have grown up to make their own movies and tell their side of the story. “A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries” (1998) was based on an autobiographical novel by Kaylie Jones, whose novelist father James raised his family in bohemian freedom as exiles in Paris. Now here is “Hideous Kinky,” based on an autobiographical novel by Esther Freud, whose father is the British painter Lucien Freud. I’m not sure how much of the story is based on fact, but presumably the feelings are accurately reflected, as when a child tells her hippie mother: “I don’t need another adventure, Mom! I need to go to school. I want a satchel!” The film stars Kate Winslet, in an about-face after “Titanic,” as a 30ish British mom named Julia, who has journeyed to Marrakech in 1972 with her two young daughters, Bea (Bella Riza) and Lucy (Carrie Mullan). She is seeking the truth, she says, or perhaps she is making a grand gesture against her husband, a London poet whom she caught cheating. Well, actually, he’s not officially her husband, although he is the father of the children and is sending them packages and checks from time to time, although sometimes they get packages intended for his other family, and the bank doesn’t often receive the checks.

Julia is not a bad woman–just reckless, naive, foolishly trusting and seeking truth in the wrong places, times and ways. She doesn’t do drugs to speak of, drinks little, wants to study Sufi philosophy. Her children, like most children, are profoundly conservative in the face of anarchy. They want a home, school, “real shirts.” They’re tired of Julia’s quest and ask, “Mom, when can we have rice pudding again?” The movie’s tension comes from our own uneasiness about the mother, who with the best intentions seems to be blundering into trouble.

The film, directed by Gillies MacKinnon, fills its canvas with details about expatriate life in the time of flower power. Moroccan music blends with psychedelic rock, and they meet a teacher from the School of the Annihilation of the Ego. The expatriate American novelist Paul Bowles is presumably lurking about somewhere, writing his novel The Sheltering Sky, which is about characters not unlike these. One day in the bazaar, the family encounters Bilal (Said Taghmaoui), a street performer who possibly has some disagreements with the police, but is humorous and friendly, and is soon Julia’s lover.

Bilal is not a bad man, either. “Hideous Kinky” is not a melodrama or a thriller, and doesn’t need villains; it’s the record of a time when idealism led good-hearted seekers into danger. Some of the time Julia doesn’t have enough food for her children, or a place for them to stay, and her idea for raising money is pathetic: She has them all making dolls to sell in the marketplace. Their trip to the desert leads to a nearly fatal ride with a sleepy truck driver, and to an uneasy meeting with a woman who may or may not be Bilal’s wife.

In Marrakech, invitations come easily. They meet a Frenchman (Pierre Clementi, who played young hippies himself in the 1960s and 1970s), who invites them to his house: “I have lots of rooms.” There they get involved in a strange menage. Later, incredibly, Julia leaves Bea with them for safekeeping, only to discover that the household has broken up and her child has disappeared. She finds Bea in the keeping of an earnest Christian woman who runs an orphanage and doesn’t seem inclined to surrender the child. “It’s what Bea always wanted,” she tells Julia. “To be an orphan?” “To be normal.” The movie is episodic and sometimes repetitive; dramatic scenes alternate with music and local color, and then the process repeats itself. What makes it work is Winslet’s performance as a sincere, good person, not terrifically smart, who doggedly pursues her dream and drags along her unwilling children. Parents, even flower-child moms, always think they know what’s best for their kids. Maybe they do. Look at it this way: To the degree that this story really is autobiographical, Julia reared a daughter who wrote a novel and had it made into a movie. Bea might not have turned out quite so splendidly by eating rice pudding and carrying a satchel to school.