A man in London orders his limousine to stop so he can buy a copy of a newspaper for Yugoslavian exiles. He turns to the obituary page and sees a name from out of his past – a name that stirs old memories and guilts. He makes arrangements to fly home for the funeral. In three other cities, three other men make the same plans. “The four” (for so they are called) meet at the graveside, and after the service they are invited by a fifth man to return to his boat for drinks.

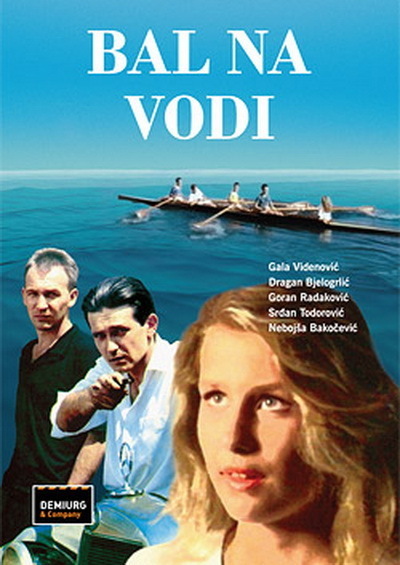

What do they have in common? They were the members of a boat racing crew. Today they have buried their coxswain, a woman named Miriana, but always called Esther, after Esther Williams, whose movies they all loved. She was a good coxswain because she was lighter than any boy, and so their crew won many races. But that is not why they flew home to Yugoslavia. They were all in love with her, and one day, in the emotionally charged early years of the Cold War, they rowed their shell all the way to Italy, right across the Adriatic, so that Esther could be reunited with her father.

In the paranoid political climate of the time, there was hell to pay because of that escapade. But “the four” received more hell on the other end, because Esther was pregnant and her father wanted to know which of them was responsible. Esther refused to name the father, none of the four stepped forward and the mystery remained a mystery ever after.

There is another person at the funeral: Esther’s daughter. “The four” approach her with sympathy. “One of us is your father,” they tell her, but she does not care, because all of that happened so long ago. If the father had not stepped forward during all the years and even decades when he had the chance, she says defiantly, what difference does it make now?

There is, we learn, a good reason why none of the four men ever identified himself as the father, and that reason is the secret of “Hey Babu Riba.” I would not dream of even hinting at it, since that would give away an element that the movie prizes highly. What I will say is that the secret is the least of this movie’s treasures and provides it with an ending that is tedious with details.

Before the film solves its mystery, however, it provides some genuine pleasures in its portrait of Yugoslavian teenagers growing up in the period between 1948 and 1954, when Tito’s nation steered an uneasy course between East and West.

Socialist dogma coexists with Glenn Miller records and the beginnings of rock ‘n’ roll, and “the four” form their own band to mimic the precious pop records that slip in from Western Europe.

They also, each in his own way, pay court to Esther, a pretty girl who loves each one of them just for being himself – something the boys’ egos will not let them understand. Each one wants to be Esther’s lover, each one is turned down, and there is some heavy-handed symbolism in which the act of smoking is made into a badge of manhood.

Since the movie begins with a funeral, it drips incessantly with nostalgia: Every happy moment we see is shadowed by the knowledge that it took place in the old days, that all the good times are past and gone. I wonder how this same material would have played if the story had been told from beginning to end. Perhaps it would have been jollier. Certainly it would have seemed more spontaneous.

And it would have allowed a more interesting treatment of the secret of the unborn child’s paternity. It is not just the secret, but the reason for the secret, that is important. The secret finally reveals itself to be based on a tragedy, and the tragedy would have seemed stronger if it were not being remembered after 30 years. The daughter is actually right: After all this time, what difference does it make?