If they were still making Westerns, the plot of “Heat” would feel right at home. It’s a movie about a dude from the East who gets tired of being pushed around and travels out West to take lessons in self-protection from a famous gunslinger. Does the story end with the timid city slicker standing up for his rights? Are there stars in the sky? But they don’t make Westerns anymore, so “Heat” is an updated version of that reliable old plot, with a few new twists. The hero uses knives and martial arts, not guns. He lives in Las Vegas, a thoroughly modern Western city, and he is a compulsive gambler. The bad guy is the spoiled son of a Mafia don from Florida.

And the final showdown takes place in a vast warehouse, just like the shoot-outs in at least 65 percent of all the other recent movies that end in shoot-outs. The only new twist is, this time, the soundtrack doesn’t use Far-Off Rattles in the silence of the warehouse; it uses Echoing Drops of Water. There’s always a basic shot in these scenes where a guy with a gun creeps along in the shadows, the gun held next to his face, the barrel pointing up. I’ve seen that shot enough for several lifetimes.

The screenplay for “Heat” was written by William Goldman, one of Hollywood’s top craftsmen, but he hasn’t outdone himself this time.

It’s all recycled material from other movies – all except for some nice personal touches added by the actors. They bring style to a movie that needs it.

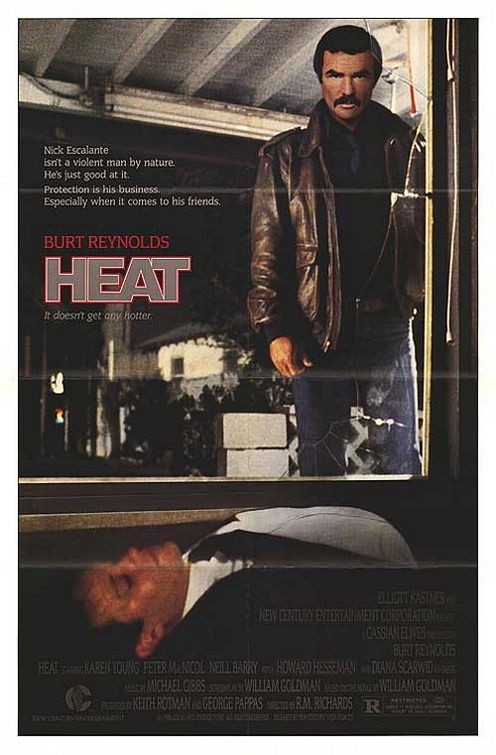

I especially enjoyed Burt Reynolds’ work as the professional tough guy. He’s a bodyguard who lists himself in the Yellow Pages under “chaperon,” a Vietnam hero who is an expert in violence but cannot contain his own compulsion to gamble. In the movie’s best sequence, he has a long winning streak at blackjack but finds that merely winning is never quite enough.

One day an out-of-towner (Peter MacNicol) hires him as a bodyguard and asks for lessons in how to act tough. Judging by MacNicol’s questions and Reynolds’ answers, they’re both cases of arrested development. MacNicol essentially wants to know how to keep that bully at the beach from kicking sand in his eyes, and Reynolds suggests pulling off the guy’s ear (“It’s surprisingly easy to do; it’s only held on by a little cartilege, and when you show a guy his ear, it grabs his attention”).

Reynolds is good in the movie’s more sustained scenes, showing toughness and weariness and a certain wry humor. The movie is a reminder that he can be a very effective movie actor. Unfortunately, he has chosen to dedicate his recent career to predictable genre movies, and “Heat” turns out to be another one, especially after the spoiled Mafia punk from Miami arrives in town. I’m getting tired of movies where the bad guy’s personality is the problem, and murdering him is the solution. Isn’t there a more interesting way for human beings to interact? There are times when “Heat” feels like a sampler from Goldman’s leftovers. The long opening sequence turns out to be a cheat on the audience. Early byplay between Reynolds and his partner (Howard Hesseman) suggests a buddy relationship that is short-circuited.

There’s a nice moment when MacNicol offers to help Reynolds with his gambling addiction, but that’s never followed up. There’s a good scene with the Mafia boss of Vegas, but then he disappears, never to be seen again. Diana Scarwid has an effective walk-on as a blackjack dealer, and then she’s gone from the movie. And so on.

The movie is filled with promising starts, but then everything dissolves into a violent action climax. There could have been a nice movie here about a coward and a gambler helping each other out. Or a lawyer and a bodyguard trying to make a living in Vegas. Or a gambler and a dealer falling in love. Or a Mafia boss trying to maintain order.

Goldman has written the first scenes for all of those movies, strung them together and thrown in a shoot-out. This movie has everything it needs except for a middle and an end.