Spike Lee brings the spirit of a poet to his films about everyday reality. “He Got Game,” the story of the pressures on the nation’s best high school basketball player, could have been a gritty docudrama, but it’s really more of a heartbreaker, about a father and his son.

Lee uses visual imagination to lift his material into the realms of hopes and dreams. Consider his opening sequence, where he wants to establish the power of basketball as a sport and an obsession. He could have given us a montage of hot NBA action, but no: He uses the music of Aaron Copland to score a series of scenes in which American kids–boys, girls, rich, poor, black, white, in school and on playgrounds–play the game. All it needs is a ball and a hoop; compared to this simplicity, Jerry Seinfeld observes, when we attend other sports we’re cheering laundry.

This opening evocation is matched by the closing shots of “He Got Game,” in which Lee goes beyond reality to find the perfect way to end his film: His final image is simple and very daring, and goes beyond words or plot to summarize the heart of the story. Seeing his films, I am saddened by how many filmmakers allow themselves to fall into the lazy rhythms of TV, where groups of people exchange dialogue. Movies are not just conversations on film; they can give us images that transform.

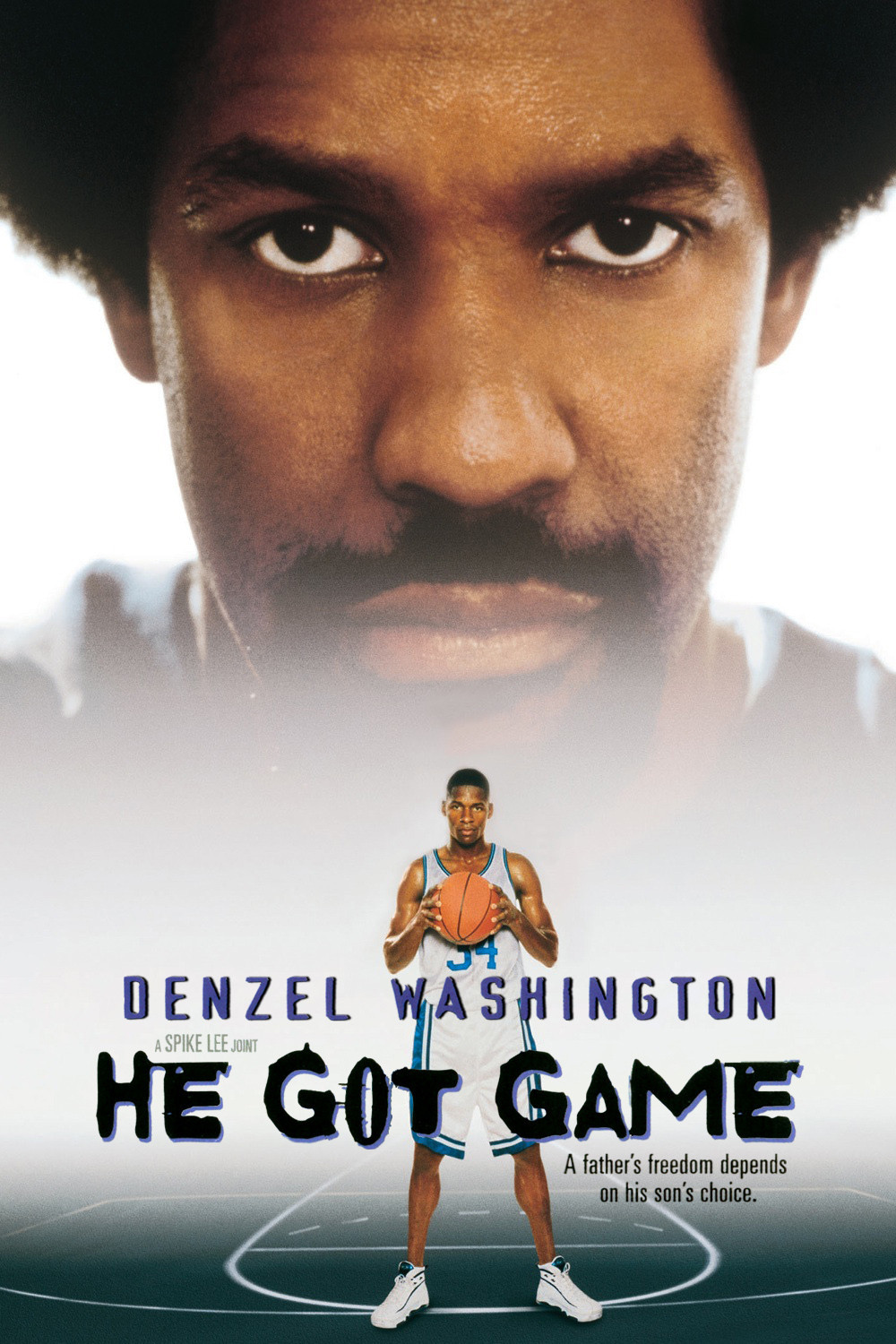

“He Got Game” is Lee’s best film since “Malcolm X” (1992). It stars Denzel Washington as Jake, a man in prison for the manslaughter of his wife (we learn in a flashback that the event was a lot more complicated than that). His son Jesus (Ray Allen) is the nation’s top prospect. The state governor makes Jake an offer: He’ll release him for a week, and if he can talk his son into signing a letter of intent to attend Big State University, the governor will reduce Jake’s sentence.

The son is not happy to see Jake (“I don’t have a father. Why is there a stranger in the house?”). He still harbors deep resentment, although his sister Mary (Zelda Harris) has understood and forgiven. Jesus (named not after Christ but after a basketball player) is under incredible pressure. Recruiting offers arrive daily from colleges, and even his girlfriend Lala (Rosario Dawson) is involved; aware that she’s likely to be dropped when Jesus goes on to stardom, she’s working with a sports agent who wants the kid to turn pro (“He’s a friend of the family,” she keeps saying, as if her family would just happen to have a high-powered agent as a pal).

Spike Lee’s connections with pro ball have no doubt given him a lot of insight into what talented high school players go through. There’s a scene in “Hoop Dreams” where he exhorts all-stars at a summer basketball camp to be aware of how they’re being used. In “He Got Game,” the temptations come thick and fast: job offers, a new Lexus, $10,000 from his own coach, even a couple of busty “students” who greet him in a dorm room with their own recruiting techniques.

Jake, on the other hand, faces bleak prospects. He moves into a flophouse next door to a hooker (Milla Jovovich) who is beaten by her pimp. Gradually they become friends, and he tries to help her. He also tries to reach his son, and it’s interesting the way Lee and Washington let Jake use silence, tact and patience in the process. Jake doesn’t try a frontal assault, maybe because he knows his son too well. Finally it all comes down to a one-on-one confrontation in which the son is given the opportunity to understand and even pity his father.

This is not so much a movie about sports as about capitalism. It doesn’t end, as the formula requires, with a big game. In fact, it never creates artificial drama with game sequences, even though Ray Allen, who plays for the Milwaukee Bucks, is that rarity, an athlete who can act. It’s about the real stakes, which involve money more than final scores, and showmanship as much as athletics.

For many years in America, sports and big business have shared the same rules and strategies. One reason so many powerful people are seen in the stands at NBA games is that the modern game objectifies the same kind of warfare that takes place in high finance; while “fans” think it’s all about sportsmanship and winning, the insiders are thinking in corporate and marketing metaphors.

“He Got Game” sees this clearly and unsentimentally (the sentiment is reserved for the father and son). There is a scene on a bench between Jesus and his girlfriend in which she states, directly and honestly, what her motivations are, and they are the same motivations that shape all of professional sports: It’s not going to last forever, so you have to look out for yourself and make all the money you can. Of course, Spike Lee still cheers for the Knicks, and I cheer for the Bulls, but it’s good to know what you’re cheering for. At the end of “He Got Game,” the father and son win, but so does the system.