The word “iconic” is said for the first time less than one minute into this documentary. It is uttered a second time before the movie’s second minute is up, this time by no less a personage than Donald Trump, who’s called a “real estate entrepreneur” in the on-screen title that first introduces him.

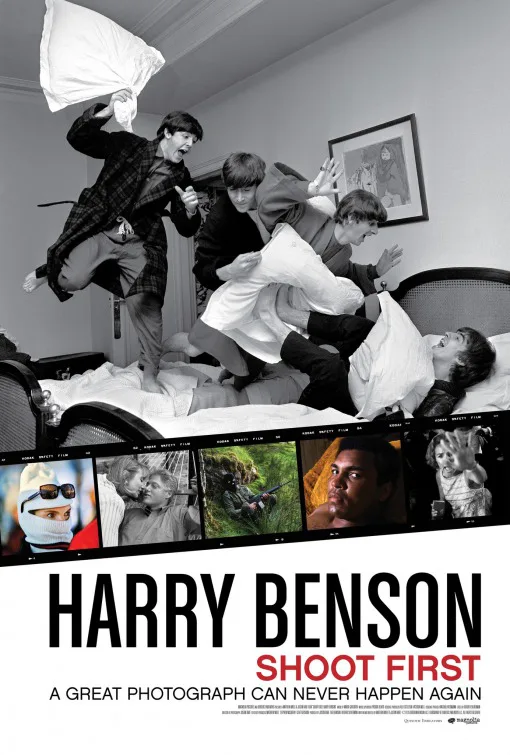

Harry Benson, now 86, is a Scotland-born photographer who came to prominence chronicling the first international tour of The Beatles. Among the “iconic” images he’s captured are winning shots of the Fab Four, in their 1964 moptop mode, engaging in a high-energy, smile-filled pillow fight in a bedroom of Paris’ Georges Cinq hotel.

A montage of these images is accompanied in this film by celebrity interviewee Dan Rather intoning, in serious-verging-on-pompous tones, the historical boilerplate about how in the wake of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, America was ready for something to cheer it up again, and what with the young people coming up, the Beatles were just the thing, and blah blah blah.

This sequence nicely encapsulates everything that’s wrong and right about this movie, directed by Justin Bare and Matthew Miele. The duo’s prior filmography, containing titles like “Crazy About Tiffany’s” and “Scatter My Ashes At Bergdorf’s,” indicates just which side of the railroad tracks they most enjoy spending time on. Hence, this is a picture that luxuriates in its celebrity power. In addition to Trump and Rather, the filmmakers get onscreen testimonials about Benson from the likes of Alec Baldwin, Sharon Stone, Bryant Gumbel, Carl Bernstein, James L. Brooks, and Henry Kissinger. (Also included are a lot of top-drawer media folk, the most entertaining of whom is, of course André Leon Talley.) It’s impressive, kind of, but it’s also a little distracting. In part because Benton himself is such a good raconteur. Recalling his assignment to follow the Beatles around, he tells of bristling at the job: “I wanted to go to Africa. I was a SERIOUS JOURNALIST.” With a frankness that distinguishes all of his recollections and observations, he reveals that he got the job because the other photographer at his paper was “ugly.” One couldn’t be around the Beatles if you were ugly, Benson says. Contemporary pictures of Benson show a serious-looking handsome gent with a healthy shock of brown hair. A companionable seeming fellow.

This quality served him well when he went on more dangerous assignments, covering the Ku Klux Klan during the civil rights movement era, befriending Martin Luther King Jr.. He was admitted to King’s hotel room after the leader’s murder, where he captured some very unusual shots. He then joined Robert Kennedy’s presidential campaign, and his camera documented some of the terrible and memorable images of the late politician directly after his shooting. Among these is an image of Ethel Kennedy with her hand raised, trying to block Benson.

Benson’s reflections on his actions at the time are interesting. He’s there as a photo journalist; it’s his job to capture the moment, no matter how awful the moment. Still. Benson, apparently a man of faith, muses that when he meets Kennedy in the next life—he clearly liked and admired the man—“I think he’ll understand.” Benson makes similar wishes about John Lennon, because Benson also took some very provocative images of Lennon’s killer, Mark David Chapman. Benson reveals that Chapman actually took the photographer aside and said to him, “I’m sorry I killed your friend.”

These moments are the best things in the movie, but they’re fleeting. As much if not more time is spent on a Jack Nicholson photo shoot in which the pictures captured a foreign substance dangling from a Nicholson nostril hair—news flash, Jack Nicholson possibly used cocaine in the 1980s—or indulging the non-Benson interviewees. Carl Bernstein is allowed to discourse on celebrity semiotics. Examining Benson’s funny and charming photos of the Beatles with Muhammad Ali (a meeting engineered by Benson in Miami), Bryant Gumbel drones “By image, by name, by voice, I don’t think there was ever a more famous person on the planet than Ali.” I know that documentary filmmakers today feel the need to Explain Things To The Kids, but, not to put too fine a point on it, at this late date you also need someone to explain to the kids who Bryant Gumbel was. Similarly, Benson will be explaining something about his process—“You want to kill something, bring it into the studio”—and boom, the filmmakers cut to Cecilia Guest (another one who needs explaining to the kids) prattling about how Benson shot her topless lolling by the swimming pool, and how scandalized her mother was, and who cares.

In the film’s last third, it finds a different footing, visiting Benson’s Glasgow roots, his oldest friend, and telling of his latter-day journeys covering famines, infitadas, and more. The filmmakers are themselves too celebrity besotted to comment in a meaningful way on how Benson’s career balanced depictions of the rich and famous with in-the-trenches risk-taking. But Benson himself hits on something pertinent when he speaks of shooting Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball in the late ‘60s: “Now it seemed much more interesting than it seemed then.”