Despite all the piety of conventional opinion, people will insist sometimes on falling in love with inappropriate partners. No thoughtful person is ever looking for an appropriate partner in the first place–they’re looking for the solution to their own needs and dreams. If you find who you need, then that’s the partner you want, no matter what your parents or society tell you. Heaven help the spouse who has been chosen for appropriateness.

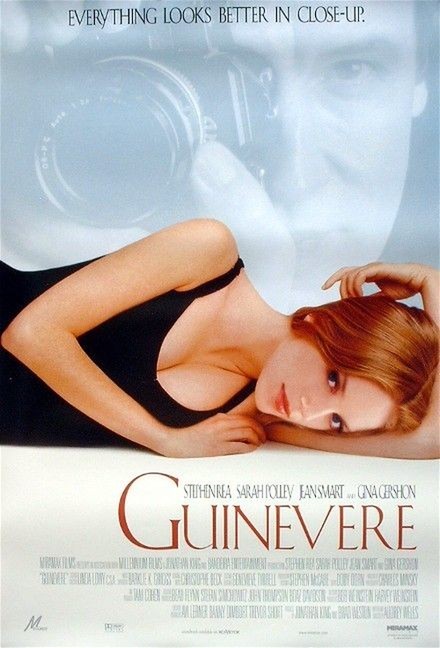

“Guinevere” is a love story involving a 21-year-old woman who is fresh, blond and vulnerable, and a man in his 50s who is a wet-eyed, hangdog drunk. “He was the worst man I ever met–or maybe the best,” she remembers four years after their affair ended. “If you’re supposed to learn from your mistakes, then he was the best mistake I ever made.” They are not a good match or even a reasonable one, but at that time, and for her needs, he was a better choice than some college boy.

The woman’s name is not Guinevere but Harper. He calls all of his women Guinevere. His name is Connie Fitzpatrick, and he’s a talented but alcoholic photographer who lives in a loft in San Francisco and specializes in mentoring young women. He also sleeps with them, but we sense that the sex is secondary to the need for proteges. Harper arrives at his loft as the previous Guinevere is tearfully leaving, and later in the film Connie is presented with a group portrait of five of his former lovers: “Your life work,” they tell him.

Harper (Sarah Polley) meets Connie at a particular time in her life. Her family is rich and cold. She is on track for Harvard but feels no calling to go there. There is no boy in her life. Anger, irony and cynicism circle the family dining table. She wants to break with this and find a partner who allows her to express her idealism. Writing those words, I realized that “Guinevere” tells the same story as “American Beauty,” with the ages and sexes reversed: The middle-aged Kevin Spacey character lusts for a high school cheerleader for the same reason that Harper knocks on the photographer’s door; what they both seek is affirmation that they are good, unique, and treasured. If you can find that in a lover, you can put up with a lot.

Connie (Stephen Rea) is, we are told, a great photographer. We are told by him. We see a few of his pictures, which are good enough, and we hear some of his beliefs, such as, “Take a picture when it hurts so bad you can’t stand it.” Well, that’s easy enough to say. He supports himself as a wedding photographer, which would seem to contradict his rule, but since it hurts really bad when he doesn’t have enough money to buy booze, maybe the rule applies.

Connie’s need is to find unformed young women and teach them. “You have to create something,” he tells Harper when she moves in. He makes her read. And she is included in his boozy philosophical round-table at the neighborhood tavern. His tragedy is that when his Guineveres learn enough, they know enough to leave. There is a horrible, perfect, brilliant moment in this film when Harper’s society-bitch mother (Jean Smart) finds out about their relationship and comes to call. She stalks the shabby loft in her expensive clothes, she smokes a cigarette with such style that he puts his own out, and in icy disdain she says, “What do you have against women your own age?” And answers her own question: “I know exactly what she has that I haven’t got. Awe.” She’s right, but can you blame him? To be regarded with awe can be a wondrous aphrodisiac. And he does care, really care, for her–for all the Guineveres. In her first night at his place, he lets her have the sleeping loft and he sleeps on the floor of his darkroom. “There’s lots of reading matter here,” he says. The book on top of the stack is the photography of Alfred Steiglitz. It falls open to a page. “That’s Georgia O’Keeffe,” she says. He tells her: “When they met, he was a famous photographer, and she was about your age.” If the movie had been 15 seconds longer, there could have been a scene showing him placing that educational volume on top of the reading matter.

The film was written and directed by Audrey Wells, who wrote the inspired romantic comedy “The Truth About Cats & Dogs.” She does not cast stones or lay blame. Wells is far beyond judging this relationship on grounds of conventional morality; it would be less moral for either one of them to settle for whoever society puts in their path.

Sarah Polley played the teenage girl in Atom Egoyan’s “The Sweet Hereafter” who surprised everyone with her testimony. She contains depths of feeling. She does not use cheap effects. There is a moment in “Guinevere” when Connie calls her his “good girl,” and I was fascinated by the subtle play of emotions on her face. The words mean a lot to her, not altogether pleasant. She is tired of being a good girl at home. Tired of being condescended to. He uses the words in a different context. She is not sure she likes that context, either, but she understands why he has to say them. There is a one-act play in the way she uses her face in that scene.

Stephen Rea, from “The Crying Game,” has a more thankless role, because he is shabby and sad. His Connie is never going to be happy (or sober), but he knows how to give a push to a shy girl with low self-esteem. One of his most touching scenes involves a carefree moment cut short by a catastrophe: His false teeth break loose. On any scale of male vanity, this ranks well above impotence. He has another scene, at the end of a disastrous trip to Los Angeles, that ranks in poignancy with some of the moments in “Leaving Las Vegas.” “Guinevere” is not perfect. Like many serious modern movies, it lacks the courage to use the sad ending it has earned. There is an absurd final fantasy scene that undoes a lot of hard work. But the movie’s heart is in the right place. This movie isn’t really about an old man and a younger woman at all. It’s about everyone’s dream of finding a person who, in the words of the old British beer commercial, refreshes the parts the others do not reach.