As “Guimba the Tyrant” opens, a dictator is instructing his son in the methods of despotism: “Your goal is to dominate men. Be cruel and merciless. Only tyranny suits them. And marry a woman coveted by all.” The son, a dwarf named Janguine, is much less interested in his father’s political theories than in his advice about women. He has been intended since birth to marry the beautiful Kani. But on a visit to his betrothed, he conceives a great lust for her mother, the voluptuous Meya. “Father,” he cries, “I love big women! With big rumps!” The father, Guimba, does not want to hear this. He has his hands full, flogging his subjects and expropriating their lands. He orders his son to marry Kani, or else. But Janguine is a spoiled little despot, and one day when Guimba comes riding back into the city, he finds his son flat on his back in the dust, crying, “I want Meya! Right now!” Solomon would have been proud of Guimba’s solution to this problem: Since his son wants to marry the mother, he himself will marry the beautiful daughter. There is a slight technicality–the mother is already married–but Guimba banishes her husband. To discourage potential suitors for the beautiful Kani, the tyrant sends his page through the town announcing, “All future suitors of Kani will be castrated!” Guimba is the ruler of a mythical African nation in pre-colonial times, but African audiences have had little difficulty in reading the movie as a parable about recent events in the nation of Mali, where the dictator Moussa Traore was overthrown in 1991 after sponsoring a reign of terror. The film’s writer and director, Cheick Oumar Sissoko, was active in the underground movement against Traore, and also has disagreements with the current regime of Alpha Oumar Konare, which did not encourage the making of “Guimba.” The film, which plays four times starting today as part of the Black Harvest film and video festival at the Film Center of the School of the Art Institute, is a riotously colorful, irreverent satire on the ways of tyrants, told in the style of the “griots,” or village storytellers, who are part of West African tradition. The story begins and ends with a griot plucking a stringed instrument while walking by a river and recounting the fall of Guimba. In these scenes he is formal and restrained, but in the heat of the story his narration grows excited and fanciful, and it is tempting to see parallels with today’s rap artists and their verbal improvisations.

The story takes place in a village of great beauty, made of concrete that has been colored ochre by the local sand. Like all fables, it occupies the entire attention of all of the characters, who have no occupations other than their task of following the events and playing their parts in them.

Guimba (Falabo Issa Traore) rules this village with an iron hand, sometimes springing from his throne to personally beat those who defy him. So great is the pressure of his villainy that he wears a headdress shielding his face from the sun. His son Janguine (Lamine Diallo) is 3 feet tall but struts around town like the boss’ son, which he is. All he has to do is raise a finger and his lackeys bring him a woman. Three fingers, three women. The local people are very tired of this, and as one wife is dragged away to serve Janguine’s pleasure, her husband beats his head against a wall.

Guimba seems to exercise total power, but in fact there are magic spells that can defeat him. When the tyrant banishes Meya’s husband, Mambi, he seeks out a band of hunters who live outside the village (and who perhaps represent exiled opponents of the Malian regime). Siriman, leader of this band, has magic so powerful he can turn day to night, and soon there is a duel to the death between the tyrant and his enemies.

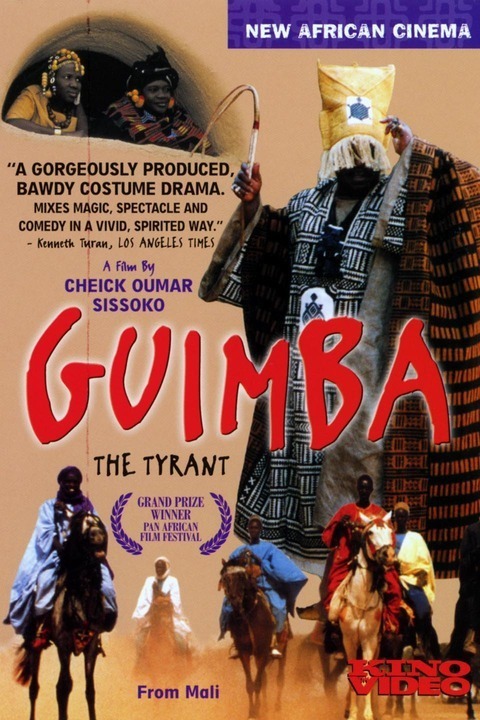

“Guimba the Tyrant” won the grand prize at the 1995 Fespaco festival, held every other year in Burkina Faso and considered the most important artistic gathering on the continent. It was also honored for its extraordinary costumes by Kandjoura Coulibaly–costumes so colorful and fanciful that if you’re at all interested in African fabrics and designs, they alone make the movie worth seeing.

In interviews, Cheick Oumar Sissoko has said his purpose was not to make a good American film or a good French film, but a good African film, and he describes the African tradition of discursive narrative as his inspiration. A good storyteller does not stay in the same tone throughout his tale, but is serious, sarcastic, fanciful and absurd as the spirit moves him. The film is told in the same way. Some scenes are played straight, some are fantasies, some are riotous action, some are comic, some are bluntly realistic. (James Joyce’s Ulysses also uses such a mixture of styles.) The result is a film that is confusing at times, but becomes clear at the end, after you see where all the pieces fit. The subtitles, which stick to the dialogue and ignore background or context, might have been more helpful at times. But the story is straightforward, the visual style is glorious, and there is boundless energy and optimism in this fable of a tyrant overthrown.