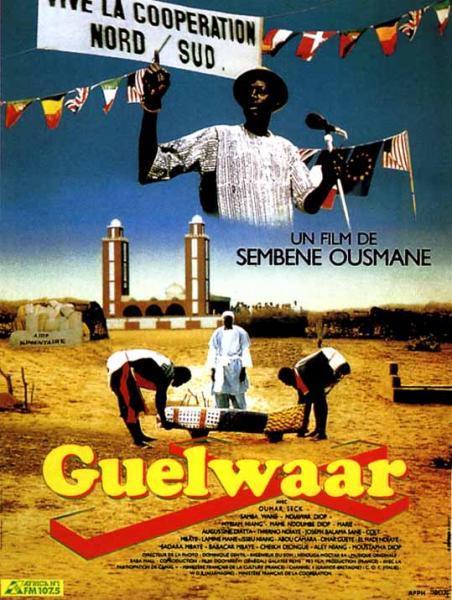

Most moviegoers hardly ever get the opportunity to see a film like “Guelwaar,” and even fewer take advantage of it. Does anyone care that Ousmane Sembene, the foremost African filmmaker, has made a film that tells a simple story and yet touches on some of the most difficult questions of our time? Moviegoers have little curiosity. Most of them will never have seen a film about Africans, by Africans, in modern Africa, shot on location. They see no need to start now (and this indifference extends, of course, to African-Americans). Movies can show us worlds and societies we will never otherwise glimpse, but most of the time we prefer to watch slick fictions with lots of laughs and action.

Enough of the sermon. What about the movie. “Guelwaar” is the name of a man who is dead at the beginning of Sembene’s film. He was, we gather, quite a guy – a district leader in Senegal who made a fiery speech against foreign aid. He felt it turned those who accepted it into slaves. Soon after, he was found dead, and by the end of the film we more or less know why he died, although this is not a whodunit.

It is, in fact, the story of his funeral. His family gathers: The older son flies home from France; a daughter who works as a prostitute returns from Dakar, the capital; and the youngest son is still in the Village. Then there is a problem. His body disappears from the morgue.

Sembene uses this disappearance, and the search for the body, to tell us a story about modern Senegal, which is a former French colony on the West Coast of Africa, with a population of about 8 million. In the district where the story takes place, the majority of people are Islamic, but there is a sizable Roman Catholic minority, including Guelwaar’s family. At first it is suspected that the body has been snatched by members of a fetishistic cult who might use it in their ceremonies, but there is a much more mundane explanation: Through a mixup at the morgue, Guelwaar has been confused with a dead Muslim, and has already been buried in the Islamic cemetery.

Sembene tells this story in a series of conversations which reveal, subtly and casually, how things work in modern Senegal. The Catholics and Muslims live side by side in relative harmony, but when a controversy arises there are always troublemakers who attempt to fan it up into sectarian hatred. As the Catholics march out to the cemetery to try to retrieve the body, they are met by a band of angry Muslims who intend to defend the graves of their ancestors from sacrilegiousness.

One of the few cool heads belongs to a district policeman, himself a Muslim, but fair-minded. He thinks it sensible that the misplaced body should be reburied in its rightful grave. He sets up a meeting between the priest and the imam of the district, both reasonable men, although sometimes hot-headed. There are moments of hair-trigger tension, when the wrong word could set off a bloody fight which might spread far beyond this small local case. And when the situation is almost resolved, an officious government official arrives (“Park the Mercedes in the shade”), and tries to play to the crowd.

The struggle over the body and its burial provides Sembene’s main plot line. But curling around beneath it are many other matters.

One of the most interesting encounters in the film is between the priest and a prostitute (a friend of the sister from Dakar), who tells him she is proud to be helping a brother through medical school, and to not be a beggar. She has arrived in the village wearing a revealing costume. The priest listens silently, and then simply says, “Try to put on something more decent.” He does not condemn her for her prostitution, and indeed the passionate message of Sembene’s film is that anything is better than begging – or accepting aid.

We learn that for long years the country fed and provided for itself. Now a drought has caused starvation. But even more fatally, Sembene suggests, the country’s political bureaucracy has grown fat and distant, fed on corruption, enriched by stealing and reselling the aid shipments from the west. In a shocking scene late in the film, sacks of grain and rice (marked “Gift of the USA”) are thrown in the road, and the people walk over them, in a homage to Guelwaar, who spoke against aid.

Guelwaar’s words are: “Make a man dependent on your charity and you make him your slave.” He argues that aid has destroyed the Senegalese economy and created a ruling class of thieves. And he shows how these facts have been obscured because political demagogues have fanned Muslim-Catholic rivalries, so that the proletariat fights among itself instead of against its exploiters.

The film is astonishingly beautiful. The serene African landscape is a backdrop for the struggle over the cemetery, and the serene colors of the landscape frame the bright colors of the African costumes. We see something of the way the people live, and what their values are, and how their traditional ways interact with the new forms of government. And it is a joy to listen to the dialogue, in which intelligent people seriously discuss important matters; not one Hollywood film in a dozen allows its characters to seem so in control of what they think and say.

Sembene’s message is thought-provoking. He does not blame the hunger and poverty of Senegal on buzz-words like colonialism or racism. He says they have come because self-respect has been worn away by 30 years of living off foreign aid. Like many stories that are set in a very specific time and place, this one has universal implications.

Ousmane Sembene is 71 years old. This is his seventh feature. Along the way he has also made many short subjects, founded a newspaper, written a novel. I am happy to have seen two of his other films (“Black Girl” and “Xala“), and with “Guelwaar” he reminds me that movies can be an instrument of understanding, and need not always pander to what is cheapest and most superficial.