“Getting It Right” is a late 1980s version of all those driven, off-center London films like “Darling,” “Georgy Girl” and “Morgan” – movies in which a wide-eyed innocent journeys through the jungle of the eccentric, the depraved and the blase, protected only by a good heart and limitless naivete.

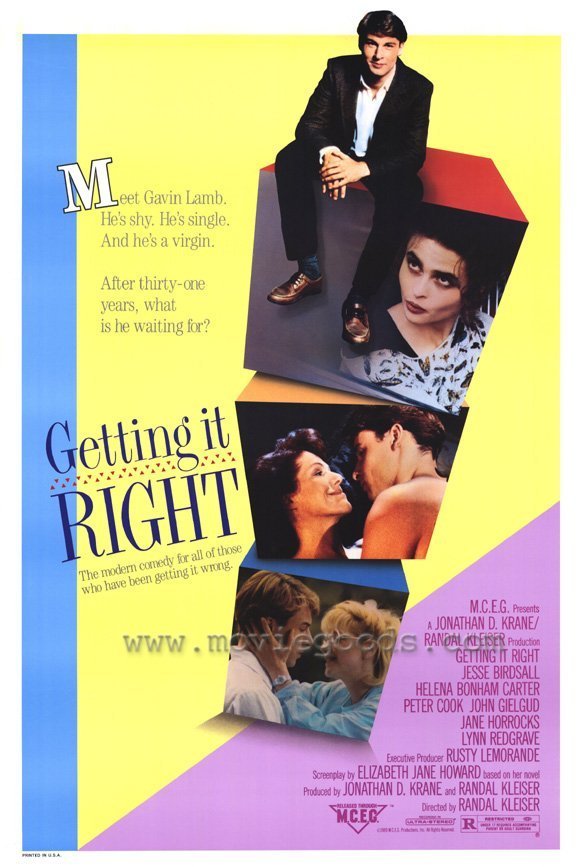

The movie tells the story of Gavin Lamb, a hairdresser who shampoos the coiffures and the miseries of his ancient clients and returns home every night to the home of his parents, where his mother serves awesomely inedible dinners promptly at the stroke of 6. Gavin is 31 and still a virgin, and his bedroom is a sanctuary where he keeps his precious collection of recorded music meticulously arranged.

At first we can’t get a reading on Gavin. He is pleasant, friendly, a little standoffish. Life doesn’t seem to have happened to him yet. The character is played close to the vest by Jesse Birdsall, a young actor who manages to look thoroughly ordinary most of the time and sublimely crafty the rest of the time. It’s a performance a little like Dustin Hoffman’s in “The Graduate,” where society is criticized by the character’s very indifference to it.

One day Gavin is taken to a party that seems to be a last-gasp attempt to resurrect Swinging London. It’s held in the spectacular penthouse of a garish divorcee (Lynn Redgrave), whose red wig and outlandish costumes look like a conscious attempt to keep people at arm’s length. But she likes Gavin, takes pity on him and invites him to a secret inner sanctum in the vast apartment – the only room, apparently, where she feels free to take off her wig and be herself.

Her secret identity turns out to be sweet and tender, and Gavin is started down the road toward losing his virginity and gaining his independence.

There is another woman at the party – a girl, really – who is dark and intense and small and determined. Her name is Minerva Munday (Helena Bonham Carter), and her father is fearsomely old and rich and eccentric (John Gielgud). Suddenly, Gavin is catapulted out of his safe orbit of the hairdressing salon and life with mum and dad, and finds his romantic life more eventful than he could have dreamed.

“Getting It Right” is a character film, not a plot film, and so the point is not what happens, but who it happens to. The screenplay is by Elizabeth Jane Howard, based on her novel, and it shows a novelist’s instinct for character and dialogue. This is not one of those mechanically plotted forced marches through film-school script formulas, but a story that lives and breathes and gives the characters the freedom to surprise us.

Smaller roles, like Peter Cook’s cameo as the owner of the hairdressing salon, are enriched with asides that suggest the entire character. And some of the characters sneak up on us – like Jenny (Jane Horrocks), who is Gavin’s assistant at the salon. He has barely looked at her in two years, but now, emboldened by his late flowering, he looks at everyone in a new light, and Jenny begins to blossom.

“Getting It Right” was directed by Randal Kleiser, whose big hit film “Grease,” in 1978 has been followed by a career with no discernable pattern (can the same director have made “The Blue Lagoon,” “Flight of the Navigator,” and “Big Top Pee-Wee?”).

With this film, however, Kleiser has gotten everything right; he is often dealing with the most delicate nuances, in which the whole point of some scenes depends on subtle reactions or small shifts of tone, and he doesn’t step wrong. Look, for example, at his control of a scene where Gavin takes a date to a birthday party for a gay friend who breaks up with his lover right there on the spot. The scene is poignant and yet still works as the comedy of embarrassment. There is a delicious delight seeing the film find its way into the lives of so many bright, lonely, mixed-up people. And “Getting It Right” does not box them into a plot, but allows them to be themselves. In a season when many movies seem to have settled into the dead repetition of formulas, this movie is alive.