“Get Real” tells the story of a teenage boy who has become sexually active at 16. That is, of course, the fodder for countless teenage sexcoms, in which the young heroes raid the brothels of Tijuana, are seduced by their French governesses, or have affairs with their teachers. The difference is that the hero in “Get Real” is gay, and so no doubt some quarters will be offended by the film. When straight teenagers do it, it’s called sowing wild oats. When gay teenagers do it, it’s hedonistic promiscuity.

In the world of certain moralists, everyone is straight and they never have sex until they’ve been united by clergy, but the real world is filled with young people who must deal everyday with strong emotional and sexual feelings. Some of them have sex. Some of them are gay. This is a fact of life.

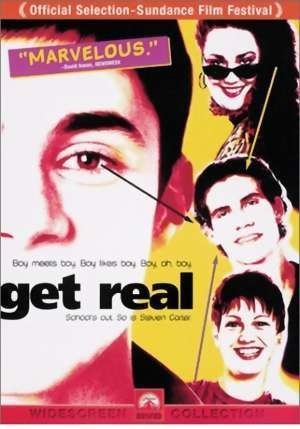

Such a person is Steven Carter (Ben Silverstone), the young British student who is the subject of “Get Real.” He has known he was gay since he was 11. He keeps it a secret because in his school, you can be beaten for being gay. He’s picked on anyway, by insecure kids who deal with their own sexual anxiety by punishing others. The cards are stacked against him. He tells a girl who’s his best friend: “I don’t smoke or play football, and I have an I.Q. over 25.” One day Steven visits a local park where gays are known to meet, and is surprised to find that John Dixon (Brad Gorton), an athletic hero at his school, is hanging out there, too–and apparently for the same reason. John is far from out of the closet. He’s attracted to Steven, and then runs away, and then comes creeping curiously back, and then denies his feelings, and there is a heartbreaking scene (after they have become lovers) where he beats up Steven in the lockerroom, just to keep his cover in front of a gang of gay-bashers.

The movie deals with this material in a straightforward way, but is not sexually graphic and it somehow finds humor and warmth even while it shows Steven’s lonely, secretive existence. In its general outlines, it’s a typical teenage comedy like the ones that have been opening every weekend all spring, where the shy outsider is surprised to attract the most popular boy in class. This time the outsider is not played by Drew Barrymore, Rachel Leigh Cook or Reese Witherspoon. And when Steven and John go to the school dance, they both dance with girls, while their eyes meet in hopeless longing.

Much of the humor in the film comes from Linda (Charlotte Brittain), Steven’s plump best friend and for a long time the only one who knows he is gay. She acts as a confidant and cover, and even obligingly faints at a wedding when he needs to make a quick getaway. He’s known her since the early days when everything he knew about sex was learned from his dad’s hidden porno tapes (“I thought babies were made when two women tie a man to a bed and cover his willy with ice cream.”).

There is also Jessica (Stacy A. Hart), an editor on the school magazine, who likes Steven a lot and wants to be his girlfriend. He would like to tell her the truth, but nobody guesses it, certainly not his parents, and he lacks the courage. Then the relationship with John helps him to see his life more clearly, to grow tired of lying, and he writes an anonymous article for the magazine that is not destined to remain anonymous for long.

The film takes a bit long to arrive at its obligatory points, and Steven’s brave decision at the end is probably unlikely–he acts not as a high school boy probably would, but as a screenwriter requires him to. But the movie is sound in all the right ways; it argues that we are as we are, and the best thing to do is accept that. I doubt if movies have much influence on behavior, but I hope they can help us empathize with those who are not like us. There were stories that the Colorado shooters were taunted (inaccurately, apparently) for being gay. Movies like “Get Real” might help homophobic teenagers and adults become more accepting of differences. Certainly this film has deeper values than the mainstream teenage comedies that retail aggressive materialism, soft-core sex and shallow ideas about “popularity.”