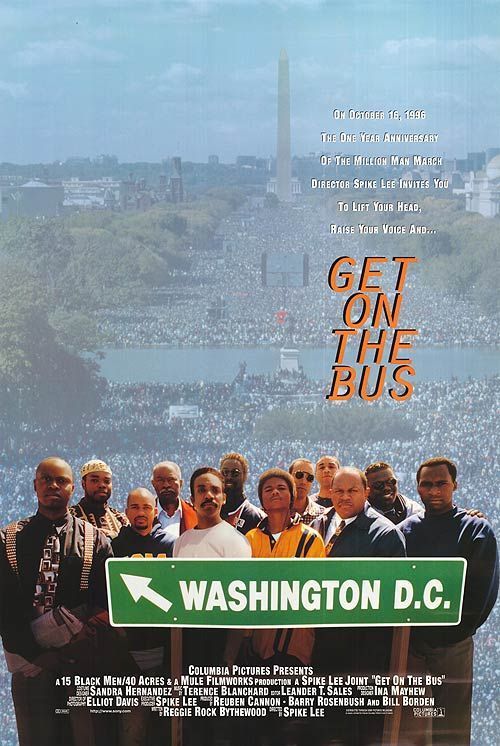

Spike Lee‘s “Get on the Bus” is a movie made in haste and passion, and that may account for its uncanny effect: We feel close to the real, often unspoken, issues involving race in America, without the distance that more time and money might have provided. The film follows a group of about 20 black men on a cross-country bus trip to the Million Man March on Oct. 16, 1995, and it opens exactly one year later.

Lee made the movie quickly, after 15 black men invested in the enterprise. He shot in 16 mm and video, always in and around the bus, using the cross-section of its passengers to show hard truths, and falsehoods, too. If the movie’s central sadness is that we identify with our own group and suspect outsiders, the movie’s message is that we have been given brains to learn to empathize.

There are all kinds of men on the bus. The tour leader (Charles S. Dutton) will be an inspiration and a referee. Another steadying hand is supplied by the oldest man on board, Jeremiah (Ossie Davis), a student of black history who delights in informing white cowboys that a black cowboy invented steer wrestling.

Also on board are a father (Thomas Jefferson Byrd) and his young son (DeAundre Bonds), who have been shackled together by a court order; the irony of going to the march in chains is not lost on the others. An ex-Marine (Isaiah Washington), who is gay, boards the bus with his lover (Harry Lennix) and they’re singled out for persecution by a homophobic would-be actor (Andre Braugher). And a light-skinned man (Roger Guenveur Smith) is revealed as a cop assigned to South Central. Then there’s a UCLA film student (Hill Harper), who is shooting a video documentary. And a member of the Nation of Islam (Gabriel Casseus), in black suit, bow tie and dark glasses, who says not one word during the journey.

During the course of the trip, conversations will be philosophical, humorous, sad, nostalgic, angry and sometimes very personal. The homosexual couple provokes the hostility of the gay-hater; prejudice knows no color line. That’s true, too, in the attitudes toward the cop, whose skin is so light that he could pass for white, and who, it is revealed, became a cop in part because his black father, also a cop, was killed (“yes,” he says, “by a brother”).

“The man says he’s black, he’s black,” pronounces Ossie Davis. But then the cop himself is revealed to have blinkers on. Another man reveals he’s a former gang member, “cripping since I smoked a guy on my 13th birthday,” but that now he does social work with “kids at risk.” No matter; the cop warns him: “When we get back to L.A., I’m going to have to arrest you.”

For many white people, a distressing element of the Million Man March was the racial slant of its convener, Louis Farrakhan, who has made many anti-Semitic and anti-white slurs. Lee could have ducked this area, but doesn’t. When the bus breaks down, the replacement driver (Richard Belzer) is a Jewish man who keeps quiet as long as he can, then speaks out about Farrakhan’s libels against Jews. “At least my parents did their part,” he says; they were civil-rights activists. He cites Farrakhan’s statements that Judaism is a “gutter religion” and “Hitler was a great man.” After some of the tour members recycle old clichés about Jewish landlords, the Belzer character says, “I wouldn’t expect you to drive a bus to a Klan meeting,” and walks away from the bus at a rest stop. Dutton takes over driving.

This is, I think, a forthright way to deal with Farrakhan’s attitudes; the bus driver expresses widely felt beliefs in the white community, and acts on his moral convictions. For the men on the bus, quite simply, “this march is not about Farrakhan.” We expect that the Nation of Islam member will speak up to defend his leader, but he never does, and his silence, behind his dark glasses, acts as a powerful symbol of a religion that none of the other men on the bus seem to relate to, or even care much about.

As the journey continues, Lee brings in other characters who illustrate the complexity of race in America. There is a satiric cameo by Wendell Pierce as a prosperous Lexus dealer, who boards the bus in mid-journey and puffs on a cigar while airily expressing self-hating cliches about blacks. Then, in Tennessee, the reason for the march comes into sharp focus when the bus is pulled over by white cops. They bring a drug-sniffing dog on board, and treat the men in a subtle but unmistakably racist way. When the cops leave, Lee gives us a series of close-ups of silent, thoughtful faces: Every black man in America has at one time or another felt charged by the police with the fact of being black.

What makes “Get on the Bus” extraordinary is the truth and feeling that go into its episodes. Spike Lee and his actors face one hard truth after another, in scenes of great power. I have always felt Lee exhibits a particular quality of fairness in his films. “Do the Right Thing” was so even-handed that it was possible for a black viewer to empathize with Sal, the pizzeria owner, and a white viewer to empathize with Mookie, the black kid who starts the riot that burns down Sal’s Pizzeria.

Lee doesn’t have heroes and villains. He shows something bad — racism — that in countless ways clouds all of our thinking. “Get on the Bus” is fair in the same sense. It is more concerned with showing how things are than with scoring cheap rhetorical points. This is a film with a full message for the heart, and the mind.